Every year, MIT Technology Review publishes a list of 10 Breakthrough Technologies, offering a glimpse into the innovations poised to shape our future. The 2026 edition, released today, marks the 25th anniversary of this esteemed compilation, meaning its journalists and editors have identified a staggering 250 technologies as potential game-changers. However, the journey from a lauded "breakthrough" to widespread adoption is often fraught with unforeseen challenges, as demonstrated by an insightful exercise conducted by Fabio Duarte and James Scott in a graduate class at MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning.

This unique course tasks MIT students with dissecting past "breakthrough" lists, specifically identifying technologies that ultimately failed to live up to their initial promise. By analyzing these "flops," students delve into the complex interplay of factors – beyond the purely technical – that dictate a technology’s success or failure. These elements include cultural context, societal acceptance, market dynamics, and even the simple vagaries of timing. This critical examination, combining a discerning perspective with creative problem-solving, is as crucial as envisioning future triumphs.

One compelling example of a technology whose vision outpaced its execution is "Social TV," featured on the 2010 list. The concept aimed to integrate social platforms and streaming services to facilitate real-time interaction with friends during live TV broadcasts, capitalizing on the ubiquity of mobile devices and broadband. While the underlying desire for connection in a digitally connected world was prescient, the focus on live TV, a medium in decline, proved to be a miscalculation. Ironically, a similar phenomenon emerged organically during the pandemic, with young people simultaneously streaming content and engaging with friends on social media and messaging apps, albeit not through a single, centralized service. This real-time, shared viewing experience, unbound by live schedules, proved more adaptable and user-driven, highlighting how innovation can manifest in unexpected ways.

The MIT course unearthed several other notable "flops" from the archives, each offering valuable lessons:

The DNA App Store (2016): Kaleigh Spears’ analysis focused on Helix, a company that offered genome sequencing for $80 and a subsequent app store where users could share their data with third parties for analysis or merchandise creation. Despite the initial allure, privacy concerns and skepticism regarding the accuracy of third-party apps, coupled with a lack of robust regulation for health apps in the US, led to the service’s demise. Helix has since shuttered its consumer-facing store, illustrating the critical importance of trust and regulatory frameworks in the burgeoning field of personal genomics.

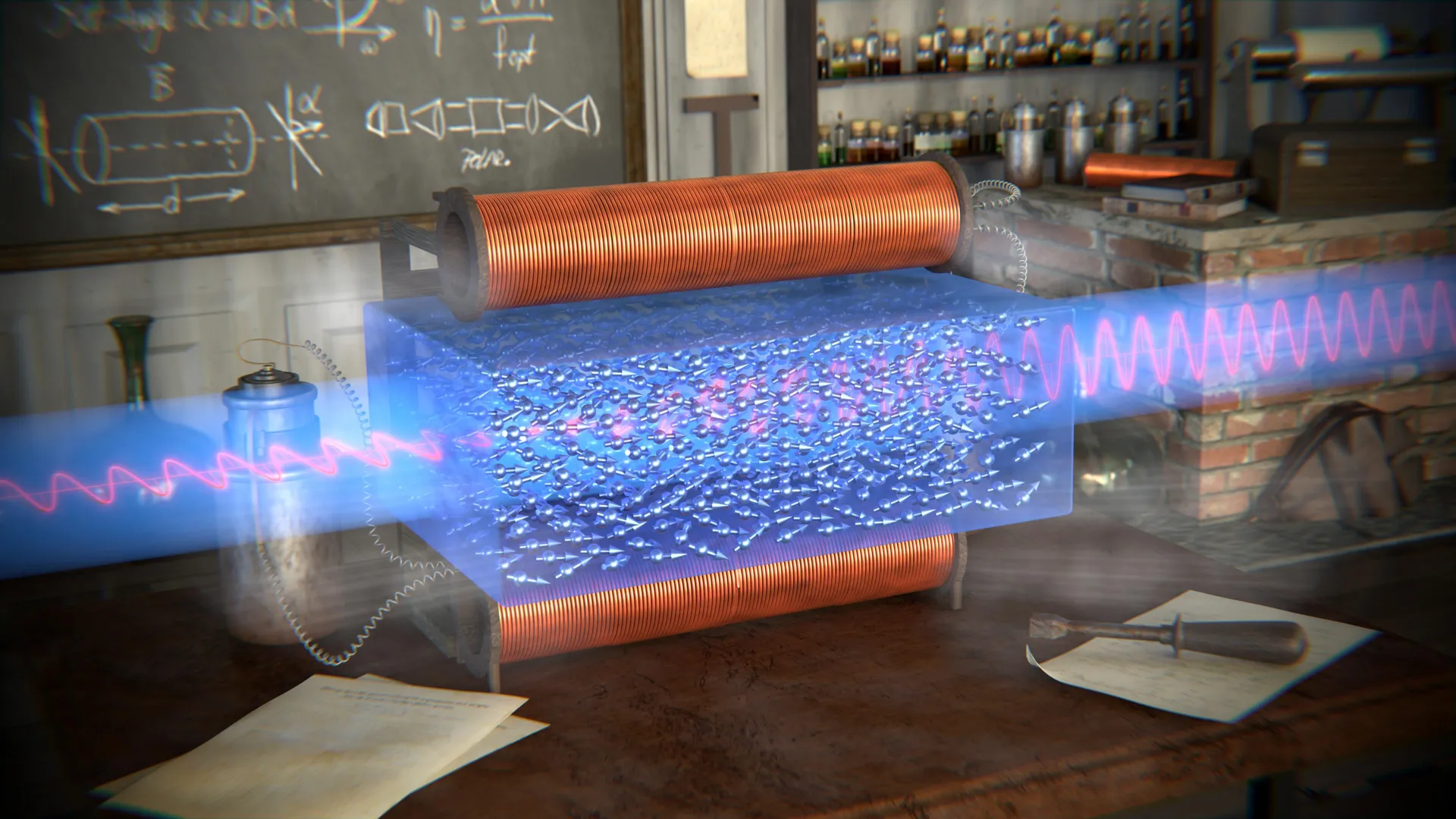

Universal Memory (2005): Elvis Chipiro examined the ambitious goal of a single memory technology to replace flash, RAM, and hard drives, spearheaded by companies like Nantero. Their approach utilized carbon nanotubes to achieve unprecedented data density. While Nantero secured substantial funding and forged licensing partnerships, scaling production proved problematic. Minute variations in nanotube arrangement caused errors, and the challenge of displacing deeply entrenched memory technologies within established manufacturing processes ultimately hindered its widespread adoption. This case underscores the immense inertia of existing industrial ecosystems and the difficulties of achieving true technological paradigm shifts.

Light-Field Photography (2012): Cherry Tang investigated Lytro’s innovative camera, which captured light rays to allow post-capture focus adjustment, promising an end to blurry photos. However, Lytro’s proprietary camera, despite its novelty, faced several hurdles. Its small display, relatively low image resolution, and the manual effort required for focus adjustments proved unappealing to consumers. Furthermore, the rapid advancement and ubiquitous nature of smartphone cameras, offering immediate convenience, significantly outmatched Lytro’s specialized offering. The company ultimately shut down in 2018, a stark reminder that even groundbreaking technology must contend with user experience and the competitive landscape.

Project Loon (2015): A recurring choice among students, Project Loon, a Google X initiative, aimed to provide internet access in remote areas using stratospheric balloons. While successful in field tests and even providing emergency service to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, the project was ultimately shut down in 2021 due to its long and risky road to commercial viability. Sean Lee identified the project’s operational focus on low-income regions, where purchasing power was limited, as a key factor. Significant commercial hurdles, including reliance on local telecom partnerships and the need for government approvals for airspace navigation, further complicated its path. However, the underlying goal of expanding internet access through high-altitude connectivity continues, with companies like Starlink pursuing similar objectives with different technological approaches, demonstrating that the core idea can persist even if the initial execution falters.

The course also prompts students to identify technologies from recent lists that they predict might face similar challenges in the future. Lynn Grosso, for instance, flagged Synthetic Data for AI (2022). While increasingly popular as real-world data becomes scarce, Grosso warns of "model collapse," where AI models trained solely on generated data may lose their connection to reality. Eden Olayiwole expressed concerns about the long-term sustainability of TikTok’s Recommendation Algorithm (2021), citing growing awareness of its potential harms and its tendency to incentivize rapid content consumption. Olayiwole proposed a "flip" for TikTok: giving users more explicit control over content and tone preferences, moving beyond passive algorithmic delivery to a more curated and intentional user experience.

The enduring lesson from years of this exercise is the nuanced reality of technological progress. The line between a successful breakthrough and a complete flop is often blurred. Some technologies, though not successful in their initial form, may lay the groundwork for future innovations (e.g., natural-language processing in 2001). Others might not have reached their full potential but still hold immense future impact (e.g., brain-machine interfaces in 2001). And some, like the malaria vaccine (2022), may require sustained investment and commitment, even when they lack immediate flashiness.

Despite the inevitable setbacks, the annual practice of identifying and discussing "breakthrough" technologies remains invaluable. It provides a vital snapshot of the technological landscape, reflecting the economic, social, and cultural values that shape our perceptions of innovation. As we look back at past lists and anticipate the future of the 2026 cohort, we gain a deeper understanding of the dynamic forces that propel some technologies forward while others gracefully recede, and crucially, what lessons we can glean from both to better navigate the ever-evolving world of innovation.