Most of us rarely question the accuracy of the GPS dot that shows our location on a map. Yet, when visiting a new city and relying on our phones for navigation, it can feel as though we’re inexplicably jumping from one spot to another, even when walking steadily along the same sidewalk. This frustrating phenomenon, where our digital location seems to betray our physical movement, is a direct consequence of the challenging environments that urban landscapes present to the Global Positioning System (GPS). As Ardeshir Mohamadi, a doctoral fellow at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), aptly explained, "Cities are brutal for satellite navigation." Mohamadi’s research is at the forefront of a crucial endeavor: making affordable GPS receivers, like those embedded in our smartphones and fitness watches, significantly more precise without resorting to costly external correction services. The implications of this work are profound, particularly for the burgeoning field of autonomous vehicles, where high accuracy is not just a convenience but an absolute necessity for safe and reliable operation.

The primary culprit behind GPS unreliability in urban settings is the phenomenon known as "urban canyons." This term aptly describes the chaotic environment created by tall buildings, glass facades, and dense infrastructure. Mohamadi elaborated on this challenge: "In cities, glass and concrete make satellite signals bounce back and forth. Tall buildings block the view, and what works perfectly on an open motorway is not so good when you enter a built-up area." When GPS signals encounter these reflective surfaces, they don’t travel directly to the receiver. Instead, they bounce off buildings, taking longer paths. This increased travel time deceives the GPS receiver, which calculates its position based on the time it takes for signals from multiple satellites to arrive. A delayed signal leads to an erroneous distance calculation, resulting in an inaccurate positional fix. Imagine being at the bottom of a deep gorge; signals reach you only after a series of reflections off the canyon walls. Similarly, in urban canyons, GPS signals undergo multiple reflections, creating a distorted and unreliable picture of the receiver’s true location. For autonomous vehicles, this distinction is critical. Mohamadi highlighted this, stating, "For autonomous vehicles, this makes the difference between confident, safe behavior and hesitant, unreliable driving. That is why we developed SmartNav, a type of positioning technology designed for ‘urban canyons’."

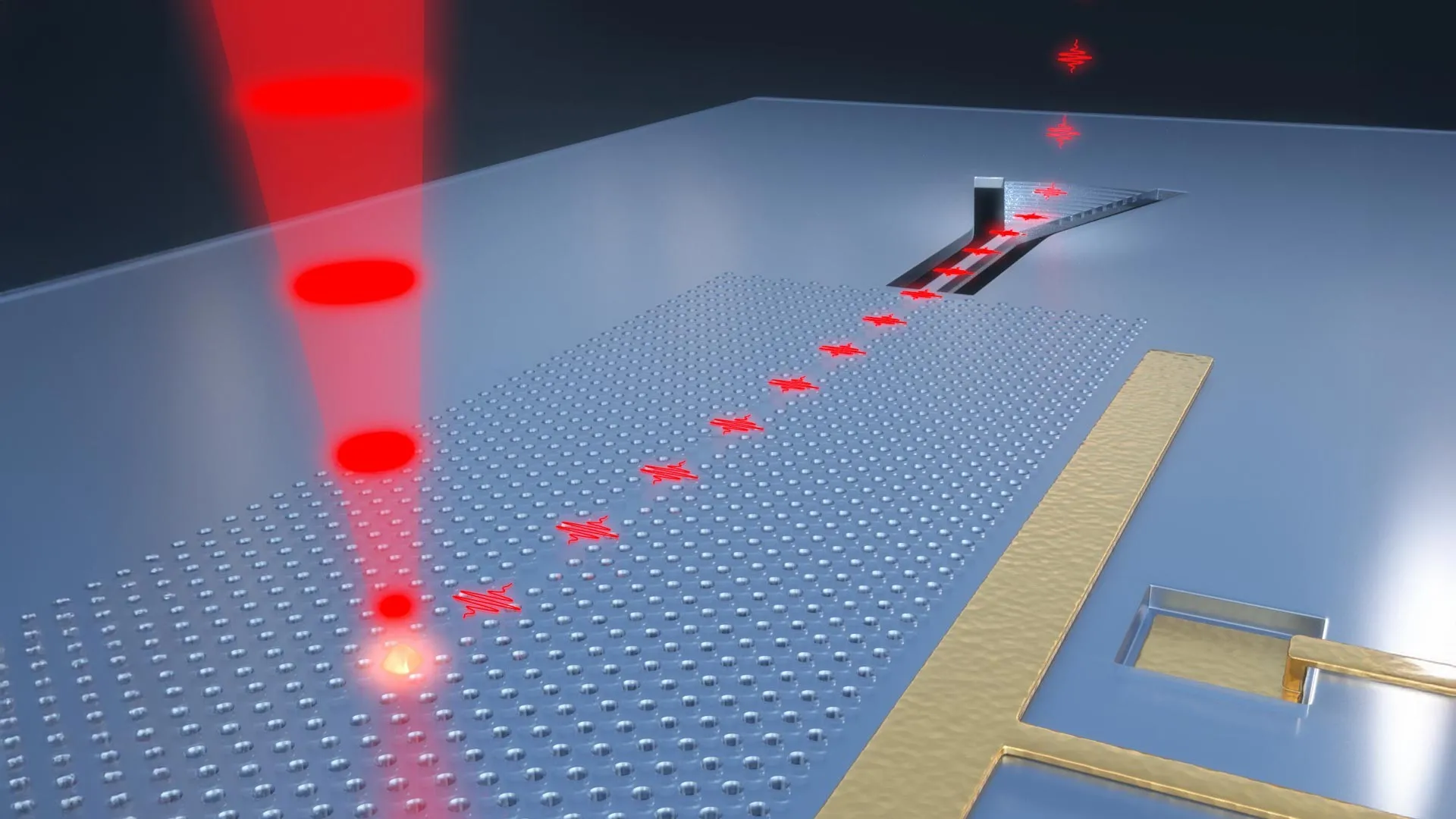

Beyond the signal reflections, another significant issue in urban canyons is the degradation of the precision of the satellite signals that do reach the receiver. Even if a signal isn’t heavily distorted by reflections, its inherent accuracy may not be sufficient for the demanding requirements of applications like self-driving cars. To address this multifaceted problem, Mohamadi and his team at NTNU have developed a sophisticated new system that ingeniously combines several different technologies to correct and enhance the GPS signal. The output of this integrated system is a computer program designed for seamless integration into the navigation systems of autonomous vehicles.

To fully appreciate the innovation, it’s helpful to understand the fundamental principles of GPS. The Global Positioning System (GPS) relies on a constellation of small satellites orbiting the Earth. These satellites continuously broadcast radio wave signals containing specific information: the satellite’s precise position in orbit and the exact time the signal was transmitted. A GPS receiver, such as the one in your smartphone, picks up these signals. By receiving signals from at least four satellites, the receiver can triangulate its position on Earth. The signal essentially acts like a text message from each satellite, conveying its location and the precise moment it sent the message.

The core of the problem in urban canyons lies in the reliability of this transmitted information. When signals bounce off buildings, the timing of their arrival at the receiver is disrupted, corrupting the positional calculation. The NTNU researchers explored a novel approach to circumvent this issue: abandoning the reliance on the coded timing information altogether. Instead, they focused on utilizing other characteristics of the radio wave itself. One such characteristic is the "carrier phase," which indicates the direction of the wave’s oscillation – whether it’s traveling upwards or downwards when it reaches the receiver. Mohamadi explained the potential of this method: "Using only the carrier phase can provide very high accuracy, but it takes time, which is not very practical when the receiver is moving." The drawback is that this method requires the receiver to remain stationary for an extended period, sometimes several minutes, to achieve a sufficiently accurate calculation. This extended waiting time is clearly impractical for navigation, especially for a moving vehicle.

Recognizing the limitations of solely relying on carrier phase, the researchers delved into other established and emerging methods for improving GPS signal accuracy. One well-known technique is Real-Time Kinematics (RTK). RTK systems utilize a network of ground-based reference stations, also known as base stations. These stations have precise, known locations and continuously broadcast correction data to nearby GPS receivers. By comparing the GPS signal received by the mobile receiver with the signal received by the base station, errors caused by atmospheric conditions and other factors can be identified and corrected. RTK offers high accuracy, but its effectiveness is limited by the proximity of the mobile receiver to a base station. Furthermore, establishing and maintaining a dense network of these stations is an expensive undertaking, making RTK primarily a solution for professional users like surveyors and agricultural operations.

A more advanced and scalable approach is Precise Point Positioning with Real-Time Kinematics (PPP-RTK). This method combines the benefits of precise positioning with the convenience of satellite-based corrections. Instead of relying on a dense network of local base stations, PPP-RTK utilizes global or regional networks of reference stations that transmit correction data via satellite. The European Galileo system, for instance, now offers this service, broadcasting its corrections free of charge, making it more accessible.

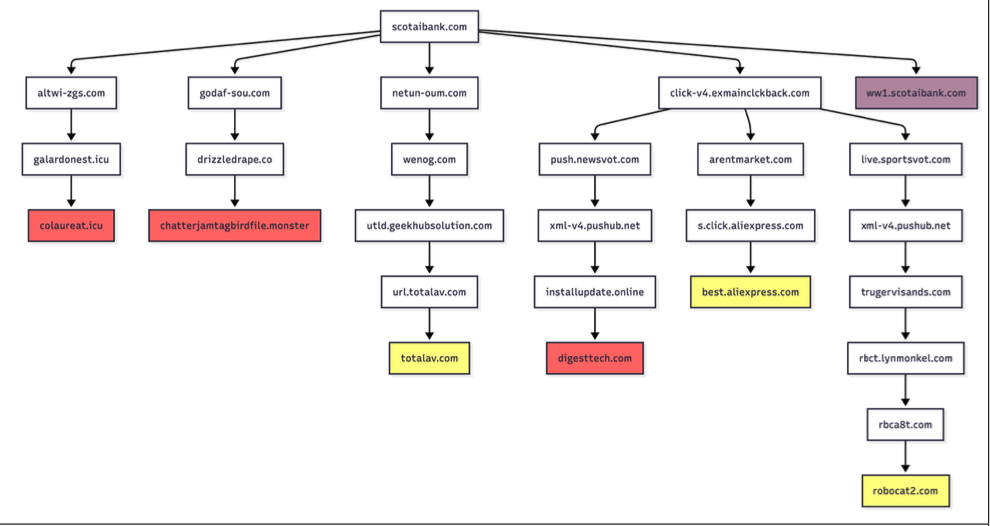

However, the breakthrough for urban navigation came from an unexpected but powerful source: Google. While the Trondheim-based researchers were meticulously refining their algorithms, Google was simultaneously developing innovative solutions for its vast user base. The company recognized the ubiquitous nature of smartphones and the increasing reliance on mapping applications for everyday navigation. For travelers planning a trip, like a hypothetical holiday to London, opening Google Maps on a tablet now allows users to not only see their location but also to virtually explore the street environment. They can zoom in on building facades and assess the height of surrounding structures, all thanks to Google’s extensive collection of 3D building models. These models, now available for nearly 4,000 cities worldwide, are not just for visualization; they are actively used to predict how satellite signals will behave within urban canyons. This predictive capability is key to overcoming the frustrating "wrong-side-of-the-street" problem, where a GPS app might erroneously place you on the opposite side of the road from your actual location.

Mohamadi explained how this Google technology integrates with other data sources: "They combine data from sensors, Wi-Fi, mobile networks, and 3D building models to produce smooth position estimates that can withstand errors caused by reflections." This multi-sensor fusion approach creates a more robust and resilient positioning system.

The NTNU researchers then ingeniously integrated these disparate correction systems – including the carrier phase information, PPP-RTK, and the Google 3D building models – with their own proprietary algorithms. The result of this synergistic effort was tested on the streets of Trondheim. The outcome was remarkable: the system achieved an accuracy of better than ten centimeters 90 percent of the time. This level of precision is a significant leap forward, providing reliability that was previously unattainable in complex urban environments.

The researchers are confident that this technology can be made accessible to the general public. The use of PPP-RTK, which reduces the reliance on expensive local infrastructure and subscriptions, makes the solution economically viable for mass-market adoption. Mohamadi concluded, "PPP-RTK reduces the need for dense networks of local base stations and expensive subscriptions, enabling cheap, large-scale implementation on mass-market receivers." This brilliant fusion of established navigation principles with cutting-edge technological advancements, including the powerful data and modeling capabilities of a tech giant, promises a future where GPS in cities is no longer a source of frustration but a reliable and precise guide, paving the way for seamless urban navigation and the widespread adoption of autonomous mobility.