However, recent groundbreaking research, spearheaded by MIT geophysicist Matěj Pešek and his colleagues, has shed significant light on this critical aspect of seismology. By employing meticulously controlled, miniature "lab quakes" under carefully calibrated conditions, the team has successfully quantified the energy budget of seismic events. These laboratory experiments, designed to mimic the fundamental physics of natural earthquakes on a much smaller scale, have yielded remarkable insights. Their findings reveal that a surprisingly small proportion of an earthquake’s total energy, estimated to be only about 1% to 10%, is actually responsible for the physical shaking of the ground that we experience. This means that the vast majority of the energy released during a seismic event is channeled into other destructive processes occurring beneath the Earth’s surface. The research further elucidates that a substantial portion of the released energy, ranging from 1% to 30%, is dedicated to the physical breaking up of rock and the creation of new fractured surfaces. This process of fracturing involves the overcoming of the rock’s tensile strength, leading to the formation of cracks and the propagation of existing ones, thereby increasing the surface area of the broken material.

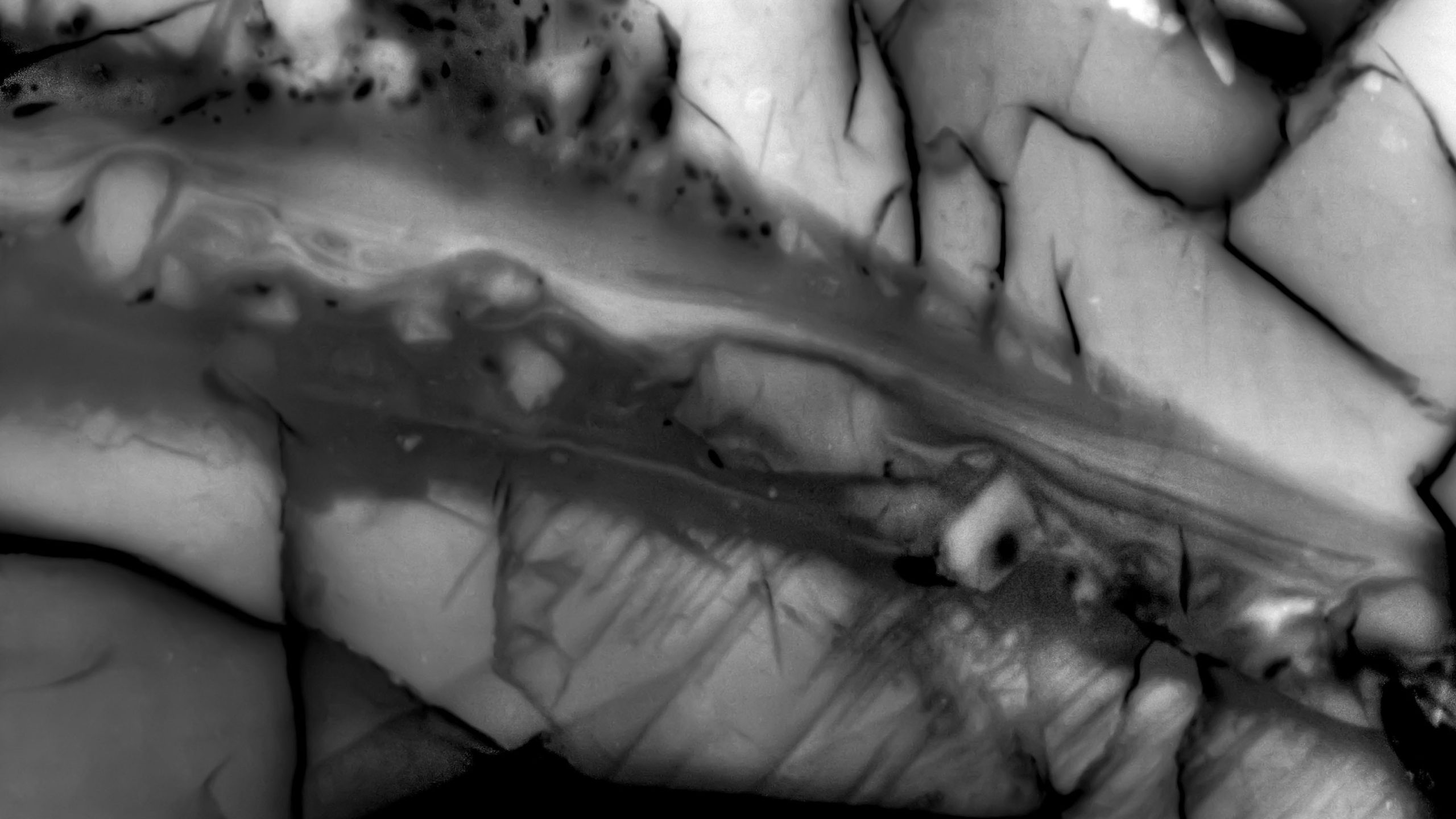

The most significant revelation from their study, however, concerns the fate of the remaining energy. The vast majority of the energy released in a quake, far exceeding that which causes shaking or fracturing, is converted into heat. This intense thermal energy is concentrated in the immediate vicinity of the earthquake’s epicenter, the point on the Earth’s surface directly above the origin of the rupture. The rapid and extreme release of energy in this localized area can lead to a dramatic spike in temperature, so significant that it can actually cause the surrounding rock material to melt. This phenomenon, known as frictional heating, is a direct consequence of the immense forces and rapid movement involved in the fault rupture. The melting of rock, even if localized and temporary, has profound implications for the subsequent behavior of the fault zone and the surrounding geological structures.

Beyond the simple partitioning of energy, the MIT team’s research has also uncovered a crucial nuance: the relative proportions of energy allocated to heat, shaking, and rock fracturing are not fixed. Instead, these fractions can dynamically shift and vary depending on the specific tectonic history of the region where the earthquake occurs. This means that the past geological experiences of a particular area exert a profound influence on how an earthquake will manifest its destructive potential. Postdoctoral researcher Daniel Ortega-Arroyo, the lead author of the paper detailing these findings, emphasized this point, stating, "The deformation history—essentially what the rock remembers—really influences how destructive an earthquake could be." He further elaborated that this geological memory, imprinted on the rock through past tectonic events, significantly alters the material properties of the rock. These altered properties, in turn, dictate to a considerable degree how the rock will behave during a subsequent rupture, influencing the slip dynamics and consequently the energy partitioning. For instance, rocks that have undergone significant prior deformation might be weaker or more brittle, leading to different energy release patterns compared to pristine rock.

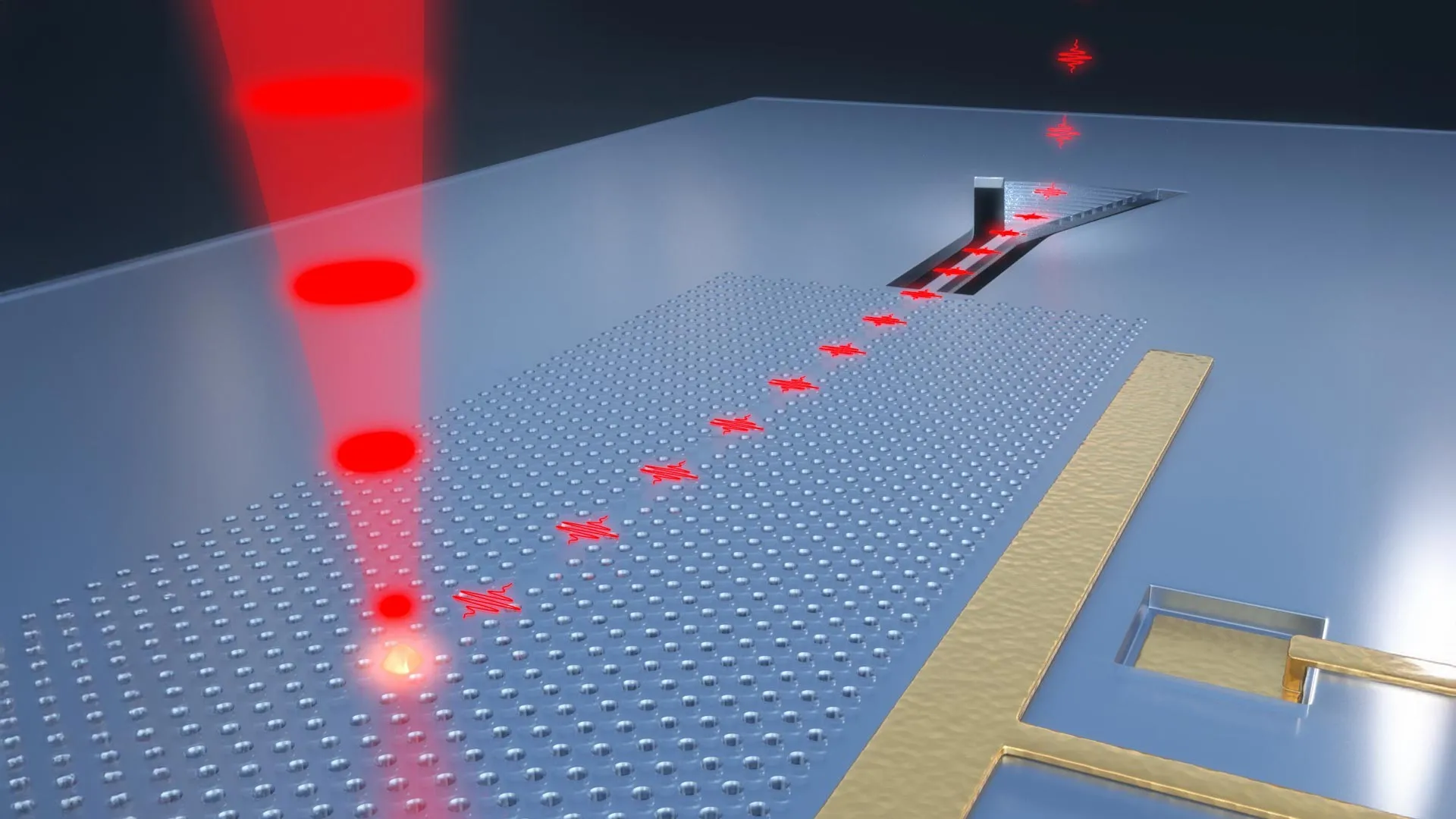

The "lab quakes" themselves are a testament to the ingenuity of modern geophysics. These experiments involve the meticulous preparation of rock samples, typically a mixture of powdered granite and magnetic particles. These carefully engineered samples are then subjected to steadily increasing pressure within a custom-built apparatus designed to precisely control and monitor the experimental conditions. This setup allows the researchers to replicate the fundamental processes of stress accumulation and sudden release that characterize natural earthquakes, albeit on a vastly reduced scale. By observing and measuring the outcomes of these controlled ruptures, scientists can extrapolate the principles governing these miniature events to the much larger and more complex phenomena of natural earthquakes.

The implications of this research extend far beyond a mere academic understanding of earthquake physics. The ability to quantify the energy budget of seismic events, and to understand how it is influenced by past tectonic activity, opens up new avenues for seismic hazard assessment and prediction. In the future, if scientists can accurately estimate the degree of shaking generated by a past earthquake, they may be able to infer the extent to which that quake’s energy also affected the rocks deep underground. This inference would be based on understanding how much energy was converted into heat and rock fracturing. By analyzing the evidence of melting or breaking of rocks, geologists could potentially gain insights into the seismic energy that didn’t manifest as surface shaking. This, in turn, could provide a more comprehensive picture of a region’s vulnerability to future seismic events. For example, a region where past earthquakes have demonstrably caused significant rock melting might indicate a geological environment that is more prone to larger energy releases or different modes of rupture in the future. Conversely, areas that show less evidence of deep subsurface damage might be less susceptible to certain types of destructive seismic activity. This advanced understanding could lead to more refined seismic hazard maps, improved building codes, and more effective disaster preparedness strategies, ultimately contributing to greater resilience in earthquake-prone regions. The research thus represents a significant step forward in our quest to understand and mitigate the devastating impacts of earthquakes.