By day, Buck contributes significantly to our understanding of human viruses, having identified four of the 13 known polyomaviruses that affect humans. These ubiquitous DNA viruses typically cause asymptomatic infections in healthy individuals but can lead to severe, even fatal, diseases in immunocompromised patients, such as organ transplant recipients. The most well-known are BK polyomavirus (BKV), which can cause nephropathy in kidney transplant patients, and JC polyomavirus (JCV), responsible for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a devastating brain disorder. The critical need for effective preventive measures for these patient populations underpins Buck’s innovative pursuit.

By night, however, Buck operates under the banner of Gusteau Research Corporation, a deliberately established one-man entity designed to afford him the autonomy to pursue his unconventional research without the stringent institutional oversight typically associated with federal scientific endeavors. It is within this private capacity that he has meticulously engineered a novel method for delivering vaccines: via brewer’s yeast. The core of his innovation lies in genetically modifying Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the common brewing yeast, to produce and display polyomavirus-like particles (VLPs) on their surface. These VLPs are remarkable biotechnological constructs: they are essentially empty viral shells, possessing the structural proteins of a virus but entirely lacking its genetic material. This means they cannot replicate or cause infection, yet they effectively mimic the virus’s outer appearance, allowing the immune system to recognize and mount a protective response against the actual pathogen.

The concept of VLPs is not new; they form the basis of several highly effective commercial vaccines, including those for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Hepatitis B. What distinguishes Buck’s work is the ingenious use of live yeast cells as a protective and proliferative delivery vehicle. Earlier research, including a 2023 study published in the journal Vaccine, demonstrated that similar VLPs, when purified and delivered via insect chitin, successfully boosted antibody levels in rhesus monkeys in India. Buck’s approach takes this a step further by leveraging the natural protective qualities of yeast. Crucially, his engineered yeast does not contain live viruses. As Buck and other researchers concur, live viruses would inevitably disintegrate upon contact with the highly acidic environment of the stomach, rendering them ineffective for oral vaccination. Yeast, however, provides a robust, natural capsule.

When Buck and his team attached these virus-like particles to live yeast, they made a pivotal discovery: these organisms could effectively carry the inoculation load through the hostile gastric environment and deliver it well beyond the stomach of live mice. This finding held immense implications, particularly for diseases like polyomaviruses, which often manifest or are significant in areas like the urinary tract. "We repeated this experiment [on mice] a couple of times. I was reluctant to believe it," Buck recounted at the World Vaccine Congress Washington earlier this year. "It felt like an earthquake when I first saw the results emerging." The potential for systemic delivery via an oral route, particularly for pathogens affecting distant sites, was a revelation.

Following these promising animal trials, Buck embarked on a phase of self-experimentation that has since become a focal point of ethical debate. He personally consumed five pints of his experimental brew, with his brother and other family members also participating. The results, as claimed by Buck, are compelling: after ingesting the experimental suds, his blood samples showed antibody levels for two of the four subtypes of BK polyomavirus that had reached a medical threshold considered safe for transplant patients. This is a significant claim, as BKV reactivation in immunosuppressed transplant patients can lead to severe kidney damage and transplant failure. An effective oral vaccine could dramatically improve the prognosis for these vulnerable individuals, offering a less invasive and potentially more accessible prophylactic measure.

However, Buck’s unconventional methodology has indeed brewed up considerable controversy. Two distinct expert panels affiliated with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) – a research review committee and an ethics committee – have explicitly voiced their opposition to Buck’s decision to experiment on himself and his family in his official capacity as an NCI virologist. Their concerns stem from several key areas: the absence of formal institutional review board (IRB) approval, which is standard practice for human subject research to ensure safety and ethical conduct; the potential for conflicts of interest when conducting private research while employed by a federal institution; and the inherent risks associated with self-experimentation outside a controlled clinical trial environment. The establishment of Gusteau Research Corporation was precisely Buck’s attempt to circumvent these institutional hurdles, allowing him to operate as a private business owner, but it does little to assuage the ethical concerns regarding the conduct of human experimentation without robust oversight.

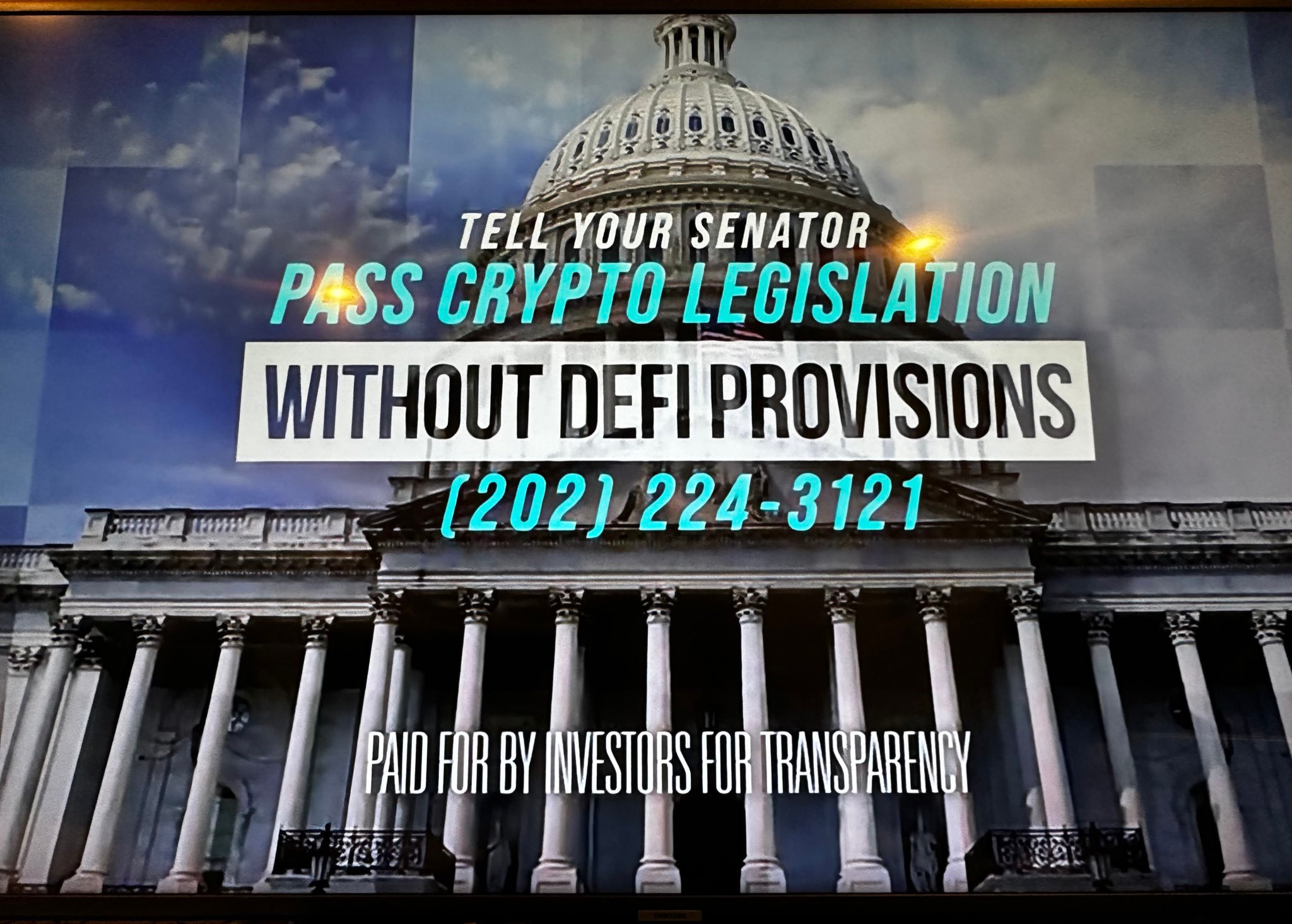

While a number of researchers interviewed by Science News acknowledged the pressing need for novel, ingestible vaccine delivery methods – praising the underlying scientific innovation of Buck’s yeast-based approach – they collectively expressed apprehension that his "cavalier attitude" toward standard research protocols could ultimately prove counterproductive. The primary worry is that Buck’s unconventional self-experimentation might inadvertently fuel the very anti-vaccine sentiment he claims to understand and challenge. Arthur Caplan, former head of medical ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, articulated this concern clearly: "Coming up with new modes of administration of vaccines is way overdue." Yet, he warned that Buck’s homebrew approach could "take a good idea he has and ruin it… vaccine doubts and fears and anti-vaccine attitudes could easily undercut what could be something useful." The chilling thought, often voiced, is: what prevents anti-vaxxers from spinning this narrative into a conspiratorial fear that vaccines could be surreptitiously dumped into mass-produced beverages like Budweiser? This scenario underscores the fragility of public trust in vaccination and the imperative for researchers to maintain impeccable ethical standards.

Buck, however, appears unfazed by the controversy, offering a unique philosophical perspective on the current state of vaccine acceptance. In a non-peer-reviewed essay posted on his personal blog, he wrote, "The basic problem for vaccine scientists has been our collective failure to understand the anti-vaxxer viewpoint." He argues that the traditional response from the scientific community – an emphasis on increasingly stringent FDA approval standards and elaborate safety protocols – has paradoxically backfired. Buck employs a vivid analogy: "Imagine if I set out to do safety testing on a banana, and I dressed up in a hazmat suit and handled the banana with tongs… you’d think: ‘wow, it looks like bananas might be about as safe as nuclear waste.’" He contends that this "security theater" has inadvertently amplified public anxieties, leading to the provocative conclusion that "All the elaborate security theater we’ve been doing ended up putting anti-vaxxers in charge of the FDA." This perspective, while controversial, highlights a deep-seated frustration within some scientific circles regarding the communication gap between experts and a skeptical public.

The broader implications of Buck’s work, both scientifically and ethically, are profound. The development of ingestible vaccines, particularly those delivered via a common foodstuff like beer, represents a significant paradigm shift. Such a modality promises numerous advantages: it eliminates the need for needles, reducing vaccine hesitancy due to injection phobia; it simplifies administration, requiring less specialized medical personnel; and it could drastically reduce logistical challenges, such as maintaining a cold chain and distributing to remote areas, thereby improving global vaccine access. This innovation opens doors for widespread vaccination campaigns, potentially reaching populations that are currently underserved by traditional injection-based methods. Other researchers are exploring similar avenues, including plant-based vaccines and probiotic delivery systems, underscoring a collective push towards more accessible and patient-friendly immunization strategies.

However, the path forward for Buck’s beer vaccine, or any ingestible vaccine, must navigate a complex landscape of scientific validation, regulatory approval, and public acceptance. Despite the initial promising results from mice and Buck’s self-experimentation, rigorous, multi-phase clinical trials involving large human cohorts are indispensable to conclusively prove safety, efficacy, and dosage. These trials must be conducted under strict ethical guidelines, with independent oversight, to ensure the protection of participants and to generate data that is credible and reproducible. Overcoming vaccine hesitancy, especially with such a novel delivery method, will require transparent communication, educational initiatives, and a meticulous adherence to scientific rigor. While Buck’s audacity has undeniably sparked a vital conversation and presented a fascinating new frontier in vaccine delivery, the challenge now lies in translating this innovative "earthquake" of an idea into a globally trusted and widely adopted public health solution, without inadvertently creating more seismic rifts in public confidence.

**More on vaccines:**Man Whose Daughter Died From Measles Stands by Failure to Vaccinate Her: “The Vaccination Has Stuff We Don’t Trust”