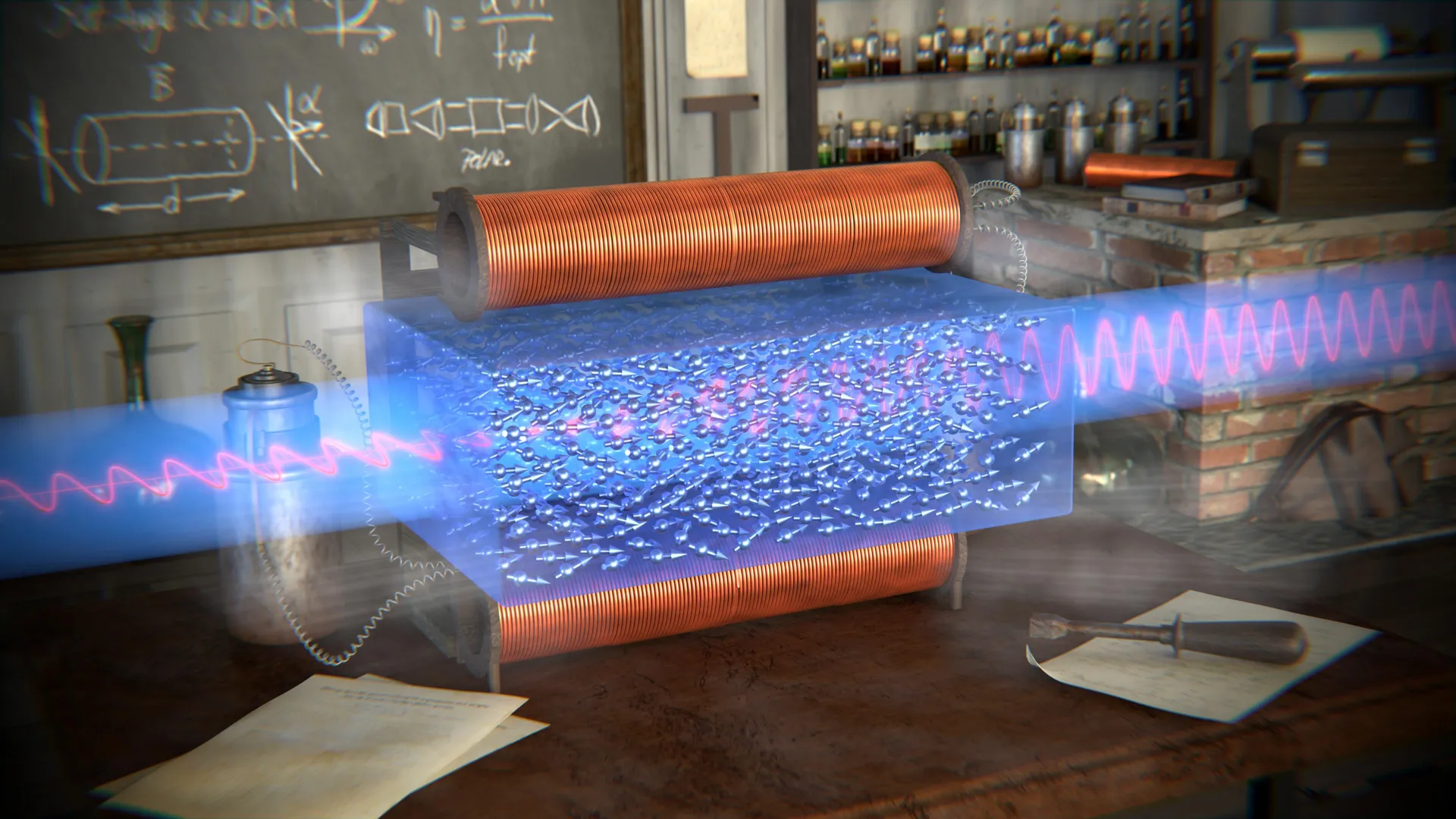

Spintronics, a burgeoning field also known as spin-electronics, represents a paradigm shift in how we process and store information. Unlike conventional electronics that solely rely on the flow of electric charge, spintronics harnesses the intrinsic angular momentum of electrons, their "spin." This quantum mechanical property, which can be visualized as a tiny internal magnetic moment, offers the potential for devices that are not only significantly faster and more energy-efficient but also capable of storing data with higher density. However, a persistent hurdle in fully unlocking the potential of spintronics has been the development of materials that can reliably and precisely control the direction of electron spin. Traditional methods often require extreme conditions like cryogenic temperatures or complex magnetic circuitry, limiting practical applications.

In a groundbreaking leap forward for spin-nanotechnology, a collaborative team of researchers, spearheaded by Professor Young Keun Kim of Korea University and Professor Ki Tae Nam of Seoul National University, has achieved a remarkable feat: the successful creation of magnetic nanohelices capable of controlling electron spin. This innovative technology, which leverages the unique properties of chiral magnetic materials to regulate electron spin at ambient room temperature, has been published in the prestigious scientific journal Science, marking a significant milestone in the field.

"These nanohelices achieve spin polarization exceeding approximately 80%, and this remarkable control is achieved solely through their intrinsic geometry and magnetism," stated Professor Young Keun Kim of Korea University, a co-corresponding author of the study. He further elaborated on the significance of their findings: "This represents a rare and powerful combination of structural chirality and intrinsic ferromagnetism, enabling efficient spin filtering at room temperature without the need for complex magnetic circuitry or cryogenics. This provides a completely new avenue for engineering electron behavior through sophisticated structural design."

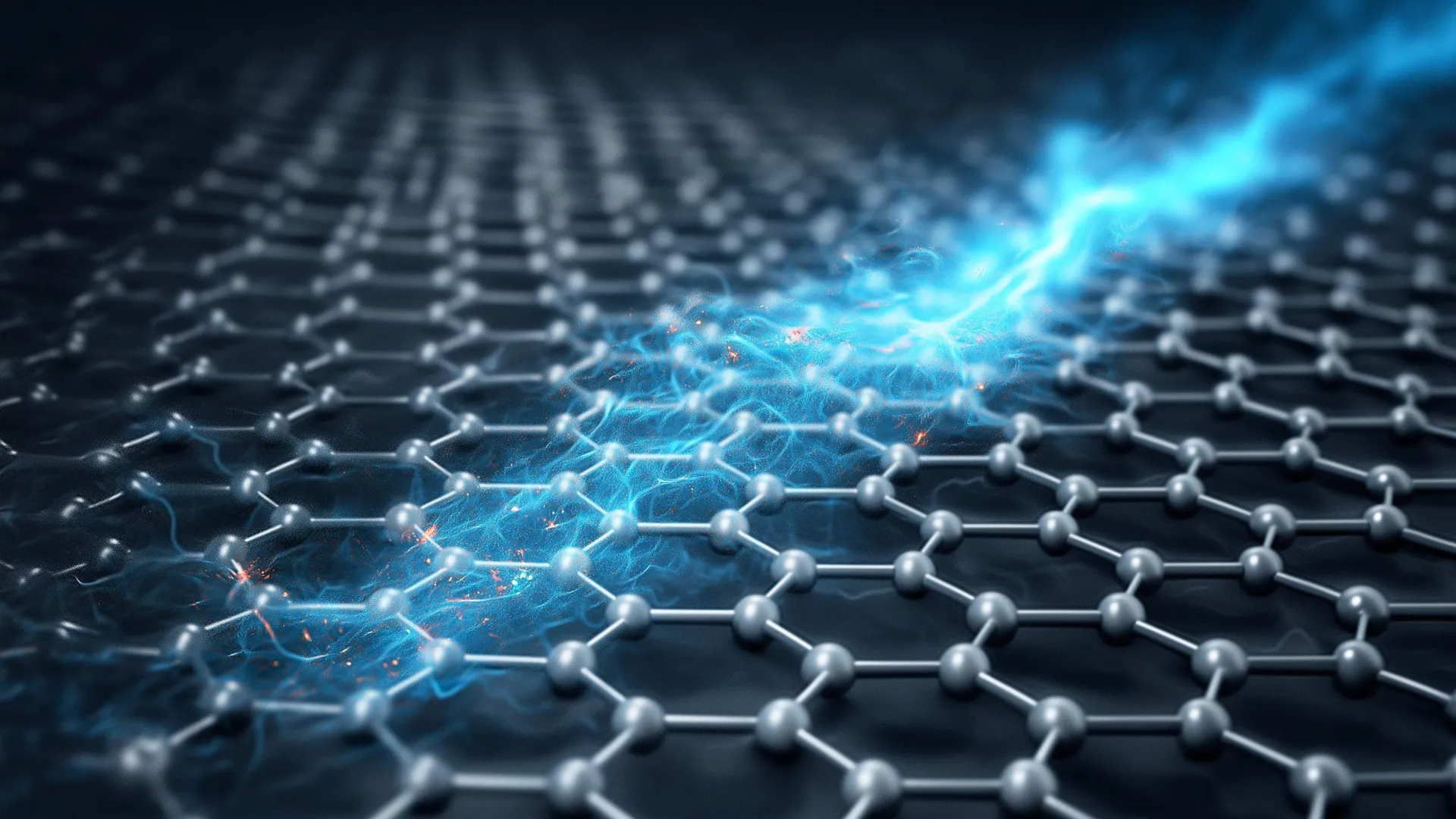

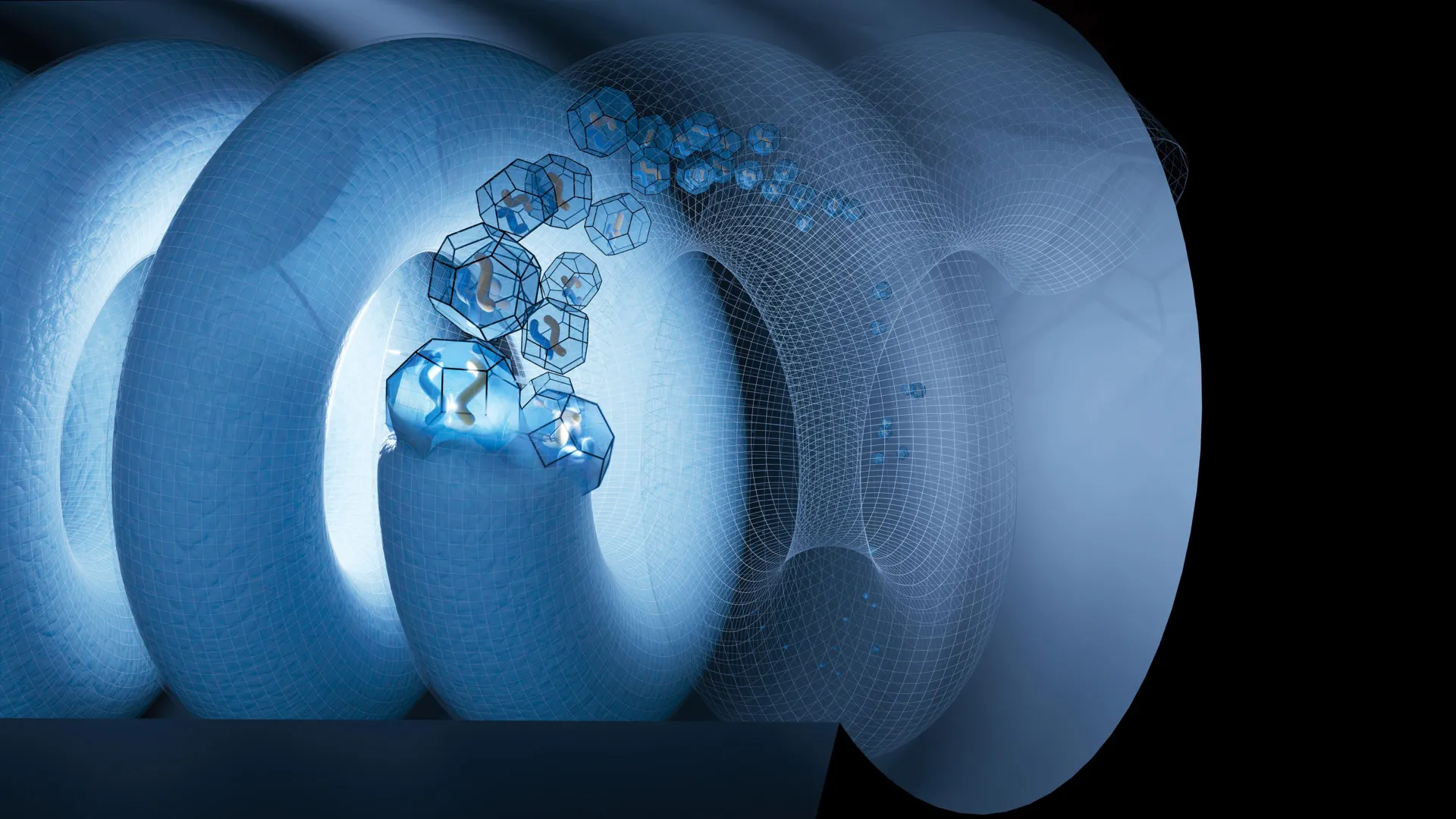

The research team’s ingenious approach involved the precise fabrication of both left- and right-handed chiral magnetic nanohelices. This was accomplished through a carefully controlled electrochemical process that dictated the metal crystallization. A critical innovation that set this work apart was the introduction of minute quantities of chiral organic molecules, such as cinchonine or cinchonidine. These molecules acted as molecular guides, directing the formation of helices with an exceptionally precise and predetermined handedness – a level of control that has historically been exceptionally difficult to achieve in inorganic material synthesis. Furthermore, the team experimentally demonstrated a crucial functional aspect: when these nanohelices exhibited a right-handedness, they preferentially allowed one specific direction of electron spin to pass through, while effectively blocking the opposite spin. This discovery represents the first instance of a three-dimensional inorganic helical nanostructure capable of actively controlling electron spin.

"Chirality, the property of a molecule or structure being non-superimposable on its mirror image, is a concept well-understood in organic chemistry, where the handedness of a structure often dictates its biological or chemical function," noted Professor Ki Tae Nam of Seoul National University, also a co-corresponding author. "However, in the realm of metals and inorganic materials, controlling chirality during synthesis, especially at the nanoscale, has proven to be an extremely formidable challenge. The fact that we were able to program the precise direction of inorganic helices simply by introducing trace amounts of chiral molecules is a genuine breakthrough in materials chemistry."

To rigorously confirm the chirality of the fabricated nanohelices, the researchers developed an innovative electromotive force (emf)-based chirality evaluation method. This novel technique allowed them to measure the emf generated by the helices when subjected to rotating magnetic fields. The results were compelling: left- and right-handed helices consistently produced opposite emf signals, providing a quantitative and reliable verification of their chirality, even in materials that do not exhibit strong interactions with light, a common limitation in other chiral characterization techniques.

Beyond their ability to control spin direction, the research team made another significant discovery: the magnetic material itself, through its inherent magnetization and aligned electron spins, facilitates long-distance spin transport at room temperature. This remarkable effect, sustained by strong exchange energy within the material, remained constant irrespective of the angle between the chiral axis of the helix and the direction of spin injection. Crucially, this long-distance spin transport was not observed in non-magnetic nanohelices of comparable scale, underscoring the critical role of magnetism in this phenomenon. This observation marks the first documented measurement of asymmetric spin transport within a relatively macro-scaled chiral body. To further solidify the practical implications of their work, the team successfully demonstrated a solid-state device that exhibited chirality-dependent conduction signals, a crucial step towards the realization of practical spintronic applications.

Professor Kim expressed his optimism about the future impact of this research, stating, "We firmly believe that this system has the potential to become a foundational platform for the burgeoning field of chiral spintronics and for the intricate architecture of novel chiral magnetic nanostructures." This groundbreaking work represents a powerful synergy between geometry, magnetism, and spin transport, all engineered from scalable and readily available inorganic materials. The versatility of their electrochemical fabrication method, which allows for precise control over the handedness (left or right) and even the complexity of the helical structure (e.g., double or multiple strands), is expected to significantly contribute to the development of entirely new application areas across various technological domains. The implications for next-generation computing, advanced sensors, and novel magnetic storage technologies are profound, as this research opens doors to a new era of spin-based innovation.