A pair of incredible images taken at the very moment two different stars exploded are also an accurate representation of how our feeble minds are being melted at the awesome but terrifying cosmic forces on display, offering an unprecedented look into the heart of stellar cataclysms that have long remained shrouded in mystery. These groundbreaking observations, captured with an array of advanced telescopes, reveal the intricate and often violent dance of binary star systems, challenging long-held assumptions about how these cosmic bombs ignite and unfold.

The images, obtained primarily using the CHARA Array at Georgia State University, illuminate a stellar calamity known as a nova. This phenomenon occurs in a binary star system where an extremely dense remnant of a star, once similar to our Sun and now a white dwarf, actively siphons material from its unfortunate companion star. This companion orbits dangerously close, constantly losing its outer layers to the white dwarf’s immense gravitational pull. As this stolen material – predominantly hydrogen – accumulates on the white dwarf’s surface, it becomes increasingly compressed and heated. Eventually, it reaches a critical mass and temperature, triggering a runaway thermonuclear explosion. This detonation is, in essence, a naturally occurring hydrogen bomb, releasing in mere moments the staggering amount of energy our Sun emits in roughly 100,000 years, yet miraculously, the white dwarf itself survives to repeat the cycle.

For centuries, astronomers could only infer the early stages of these formidable blasts. Despite lighting up the night sky, often becoming visible to the naked eye for a period, direct observations of the initial moments of a nova proved exceptionally difficult. The exploded material appeared as a single, unresolved point of light, impenetrable to finer probing by even the most powerful conventional telescopes. This limitation meant that the intricate dynamics and immediate aftermath of these violent events remained largely theoretical. Now, with these new images and the sophisticated techniques employed, scientists are gaining an unprecedented peek behind the curtain of these stellar fireworks, watching the explosions unfold in real-time and detail previously unimaginable.

"These observations allow us to watch a stellar explosion in real time, something that is very complicated and has long been thought to be extremely challenging," stated Elias Aydi, lead author of a groundbreaking new study published in the journal Nature Astronomy, and a distinguished professor of physics and astronomy at Texas Tech University. In a statement accompanying the work, Aydi emphasized the transformative nature of these findings: "Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold." This breakthrough marks a significant leap forward, moving from theoretical models and indirect evidence to direct visual confirmation of the violent processes at play.

The key to this observational triumph lies in a sophisticated technique known as interferometry. The CHARA Array, located atop Mount Wilson in California, is not a single telescope but a network of six separate optical telescopes spread across a large area. By combining the light collected by these individual telescopes, researchers can effectively synthesize a much larger, virtual telescope with an angular resolution far exceeding that of any single instrument. This allows them to resolve incredibly fine details in distant objects, details that would otherwise be blurred into a single point of light. The CHARA data was further enriched and complemented by imaging from other powerful astronomical instruments, including NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, a space-based observatory specifically designed to detect high-energy emissions, and the Gemini Observatory in Hawaii, providing crucial multi-wavelength insights. This multi-messenger approach, combining different types of electromagnetic radiation, paints a far more complete picture of these dynamic events.

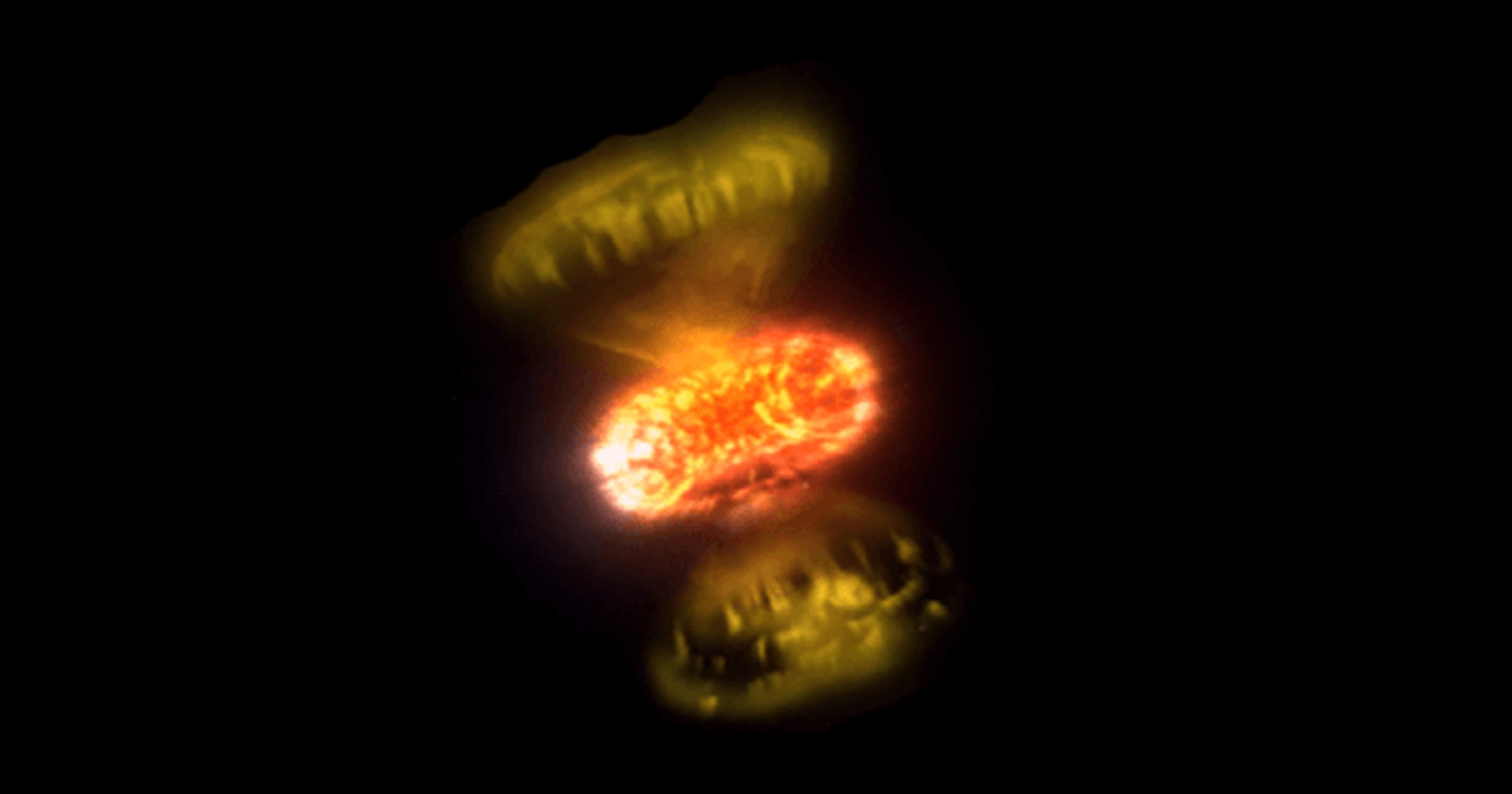

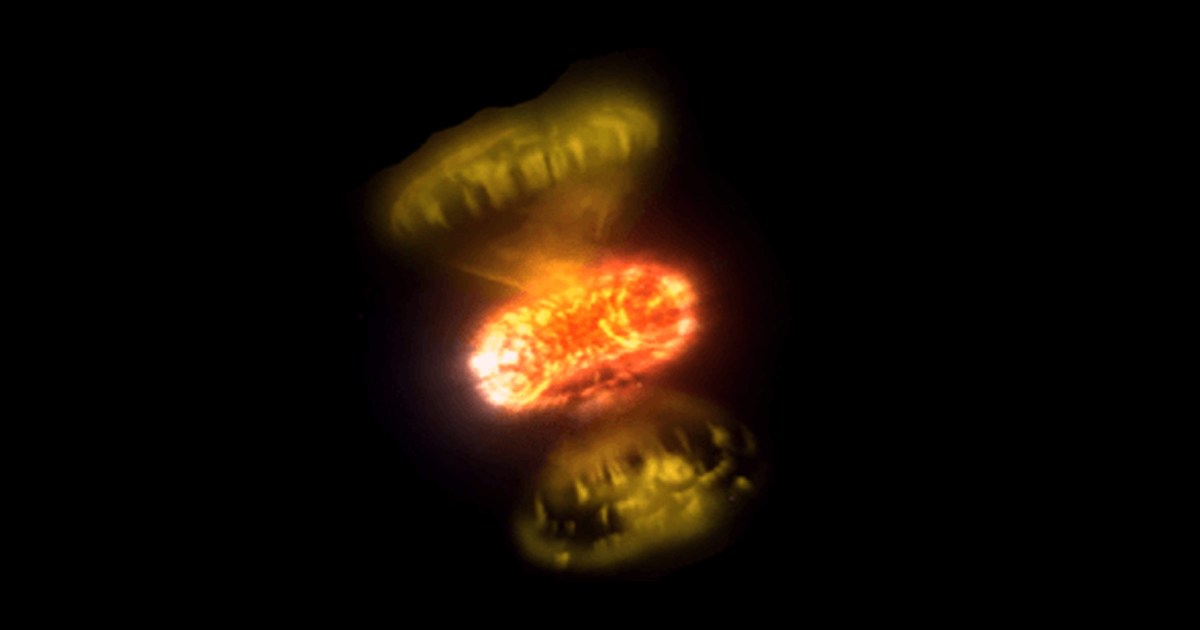

The work revealed that novas are far more complex and varied than previously assumed, defying reduction to a single, destructive blast. Each observed nova presented its own unique, intricate narrative of stellar violence. One of the imaged novas, designated V1674 Herculis, proved to be one of the fastest novas on record. Its rapid ascent to peak luminosity, followed by a swift fading over just several days, presented an extraordinary challenge to existing models. What truly astonished researchers were the images revealing two distinct outflows of gas emanating from the explosion. This intricate structure strongly suggested that the explosion involved multiple powerful ejections of material that dynamically interacted with each other, rather than a simple, symmetrical expansion. Even more remarkable was the detection of gamma rays from these ejections by NASA’s Fermi telescope. The presence of such high-energy radiation is typically associated with the most extreme cosmic events, like black hole-forming supernovae, making its detection from a relatively "smaller" nova explosion a profound and unexpected discovery. This indicates that novas are capable of accelerating particles to relativistic speeds, creating conditions ripe for extreme physics.

The other imaged nova, V1405 Cassiopeiae, offered a stark contrast to its rapid counterpart, seemingly unfolding in spectacular slow motion. This nova took more than fifty days to finally eject all of its exploded material, providing astronomers with an extended viewing window into its dramatic evolution. Over the course of this nearly two-month period, the white dwarf became completely shrouded in a vast, expanding sphere of the stripped gas. In a truly rare and captivating phenomenon, this expanding envelope of gas eventually grew large enough to engulf both the white dwarf and its companion star, forming an extremely rare and transient structure known as a common envelope. This phase is crucial in binary star evolution, often leading to significant orbital decay and shaping the future of the system, potentially setting the stage for even more exotic stellar events or future Type Ia supernovae. Remarkably, when this common envelope finally dispersed and its material was ejected into space, the process itself produced its own distinct blast of gamma rays, which NASA’s Fermi telescope was also able to observe. This observation further underscores the complex energy transfer and particle acceleration mechanisms at play, even in the "cooling down" phases of a nova.

The fact that both of these distinctly different nova events produced detectable gamma rays is a revelation. It transforms our understanding of novas, elevating them from mere "flashes" to "laboratories for extreme physics," as coauthor Laura Chomiuk, a professor of physics and astronomy at Michigan State University, eloquently put it in the statement. This insight is critical because it could help us "connect the dots between the nuclear reactions on the star’s surface, the geometry of the ejected material and the high-energy radiation we detect from space." The gamma-ray emissions suggest that shock waves generated by the expanding ejecta or the interaction of different outflow components accelerate particles to incredible energies, similar to processes seen in supernova remnants or active galactic nuclei. Understanding these acceleration mechanisms in a nova setting provides a unique, closer-to-home cosmic laboratory to study such fundamental astrophysical processes.

Beyond the immediate dynamics, these observations have profound implications for our understanding of stellar evolution and galactic chemical enrichment. Novas, while not destroying the white dwarf, do eject significant amounts of processed material into the interstellar medium. This material, enriched with heavier elements forged during the thermonuclear runaway, contributes to the chemical makeup of future generations of stars and planets. The diverse geometries and energy outputs observed in these new images will undoubtedly lead to significant refinements in theoretical models of nova outbursts, allowing scientists to better predict their frequency, luminosity, and nucleosynthetic yields. The ongoing quest to unravel the secrets of these cosmic explosions continues, fueled by the breathtaking precision of modern astronomical instruments and the insatiable curiosity of humanity to understand its place in the grand, terrifying, and utterly spectacular universe.