The United Kingdom government, through its visionary Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA), is making a significant investment in the future of scientific discovery by backing a new generation of “AI scientists.” These sophisticated artificial intelligence systems are being developed by a consortium of startups and universities, with the ambitious goal of autonomously designing, executing, and analyzing laboratory experiments. This initiative signals a dramatic acceleration in the pace of scientific progress, as evidenced by ARIA’s receipt of 245 high-caliber proposals from research teams already at the forefront of automating laboratory work.

ARIA defines an AI scientist as a comprehensive system capable of managing an entire scientific workflow. This includes the crucial stages of generating hypotheses, meticulously designing experiments to rigorously test those hypotheses, and then impartially analyzing the resulting data. In a remarkable display of iterative learning, these AI systems are engineered to feed their findings back into themselves, enabling a continuous cycle of hypothesis refinement and experimental validation. Within this paradigm, human scientists transition from hands-on experimenters to strategic overseers, setting the initial research questions and then entrusting the AI with the complex and often time-consuming execution of the scientific process.

Ant Rowstron, ARIA’s Chief Technology Officer, articulated the rationale behind this shift, stating, “There are better uses for a PhD student than waiting around in a lab until 3 a.m. to make sure an experiment is run to the end.” This sentiment underscores the agency’s commitment to optimizing human intellect for higher-level cognitive tasks, freeing researchers from tedious, repetitive, and time-sensitive laboratory duties.

From the 245 submitted proposals, ARIA has strategically selected 12 projects for funding. The agency’s enthusiasm for the quality and quantity of submissions led it to double its initial funding allocation for this competition. The selected teams represent a diverse global talent pool, with half originating from the UK and the remainder hailing from leading research institutions in the United States and Europe. The participating entities span both academic and industrial sectors, reflecting a broad-based recognition of AI’s transformative potential in science. Each funded project will receive approximately £500,000 (roughly $675,000 USD) to support nine months of intensive work. The overarching objective for these teams is to demonstrate, by the end of this period, that their AI scientist has successfully generated novel scientific findings.

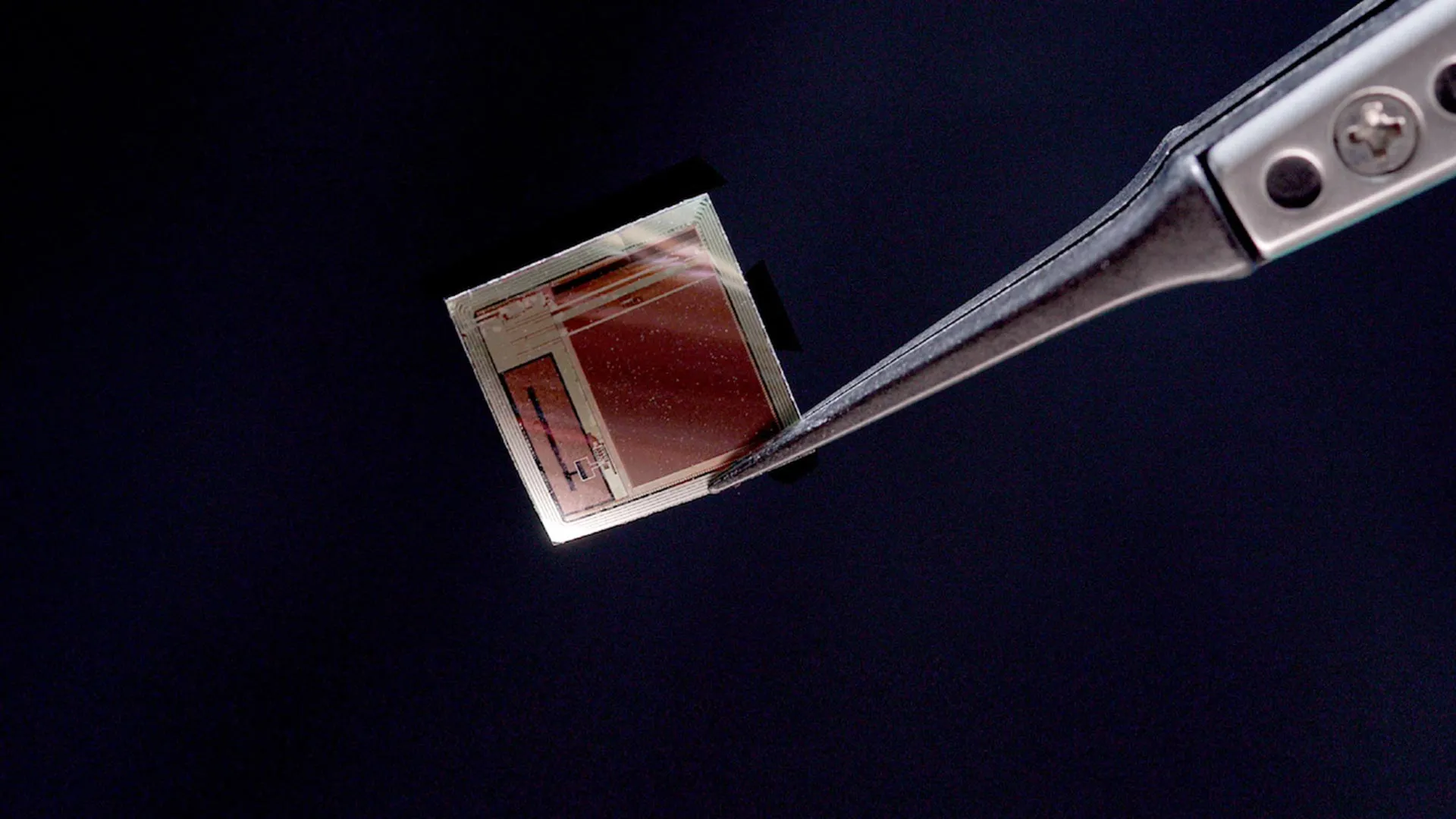

Among the distinguished winning teams is Lila Sciences, a US-based company that is pioneering what it terms an “AI nano-scientist.” This groundbreaking system is designed to independently design and conduct experiments aimed at identifying the optimal methodologies for composing and processing quantum dots. These minuscule semiconductor particles, measuring mere nanometers in scale, are critical components in a wide array of advanced technologies, including sophisticated medical imaging equipment, highly efficient solar panels, and cutting-edge QLED televisions.

Rafa Gómez-Bombarelli, Chief Science Officer for Physical Sciences at Lila, emphasized the strategic importance of this grant: “We are using the funds and time to prove a point. The grant lets us design a real AI robotics loop around a focused scientific problem, generate evidence that it works, and document the playbook so others can reproduce and extend it.” This statement highlights the project’s dual goals of achieving tangible scientific breakthroughs and establishing a replicable framework for future AI-driven scientific endeavors.

Another promising initiative comes from the University of Liverpool in the UK. This team is developing a sophisticated robot chemist capable of executing multiple experiments concurrently. A key feature of this system is its integration of a vision language model, which provides advanced troubleshooting capabilities when the robot encounters errors during its automated experimental runs.

Furthermore, a stealth-mode startup based in London is developing an AI scientist named ThetaWorld. This ambitious project leverages large language models (LLMs) to design experiments focused on the intricate physical and chemical interactions that are paramount to enhancing battery performance. The actual execution of these AI-designed experiments will be undertaken by Sandia National Laboratories in the US, utilizing their state-of-the-art automated laboratory facilities.

ARIA’s approach to funding these “AI scientist” projects is itself an experiment. In contrast to its typical funding of larger, multi-year projects often valued at £5 million, the £500,000 grants for these nine-month initiatives are deliberately modest. As Rowstron explained, the agency is using this approach to “take the temperature at the cutting edge.” By supporting a diverse array of projects over a short duration, ARIA aims to gain critical insights into the evolving landscape of scientific methodology and the velocity of its transformation. The knowledge gleaned from this initiative will serve as a foundational baseline for shaping ARIA’s future, larger-scale funding strategies.

Rowstron candidly acknowledges the significant “hype” surrounding AI in science, particularly as major AI companies increasingly dedicate teams to scientific research. He points out the challenge of discerning genuine technological capabilities from promotional claims, especially when results are disseminated through press releases rather than peer-reviewed publications. “That’s always a challenge for a research agency trying to fund the frontier,” he stated. “To do things at the frontier, we’ve got to know what the frontier is.”

Currently, the leading edge of this technology involves “agentic systems” that can dynamically call upon and integrate existing tools on demand. Rowstron described this process: “They’re running things like large language models to do the ideation, and then they use other models to do optimization and run experiments. And then they feed the results back round.”

Rowstron conceptualizes this technological evolution in distinct tiers. At the foundational level are AI tools developed by humans for human use, such as DeepMind’s AlphaFold. While these tools enable scientists to bypass slow and laborious steps in the research pipeline, they still often necessitate months of subsequent laboratory work for result verification. The ultimate aspiration of the AI scientist concept is to automate this laboratory verification phase as well.

AI scientists, in Rowstron’s framework, occupy a layer above these human-created tools, leveraging them as needed. However, he envisions a future, not decades away, where an AI scientist layer will recognize the need for novel tools that do not yet exist. At that point, the AI scientist will not only call upon existing tools but will also possess the capability to create new ones, analogous to how AlphaFold was developed, as a means to solve other, more complex problems. This would effectively automate the entire foundational tier of AI tool development.

This advanced stage of AI self-creation is still some distance off, Rowstron cautioned. All the projects currently funded by ARIA involve AI systems that utilize existing tools rather than generating entirely new ones.

Significant challenges remain with agentic systems in general, which currently limit their autonomous operational duration without deviating from their objectives or introducing errors. For instance, a recent study titled “Why LLMs Aren’t Scientists Yet,” posted online by researchers at Lossfunk, an AI lab in India, reported that in an experiment designed to assess LLM agents’ ability to complete a scientific workflow, the system failed in three out of four attempts. The researchers identified reasons for these breakdowns, including shifts in initial specifications and an “overexcitement that declares success despite obvious failures.”

“Obviously, at the moment these tools are still fairly early in their cycle and these things might plateau,” Rowstron commented. “I’m not expecting them to win a Nobel Prize.”

However, he concluded with a forward-looking perspective: “But there is a world where some of these tools will force us to operate so much quicker. And if we end up in that world, it’s super important for us to be ready.” This statement underscores the UK government’s proactive stance in anticipating and preparing for the profound societal and scientific shifts that AI scientists are poised to bring about.