"Radiative cooling is universal—it exists everywhere in our daily life," explains Qiaoqiang Gan, a distinguished professor of materials science and applied physics at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. At its core, the principle is remarkably simple: virtually any object absorbs solar radiation during the day and then radiates a portion of that absorbed heat back into the atmosphere. Gan illustrates this with a common observation: the condensation that forms on cars parked outdoors overnight. The metal roofs of these vehicles efficiently radiate heat into the vastness of the sky, causing the surface temperature to drop below the ambient air temperature, a phenomenon that leads to the formation of dew. This fundamental natural process, the dissipation of heat through radiation, has been understood and subtly utilized by humans for millennia.

Ancient civilizations, particularly in arid regions like Iran, North Africa, and India, ingeniously harnessed radiative cooling. These cultures developed methods for producing ice by leaving shallow pools of water exposed to the clear desert skies during the night. Under these conditions, the natural process of radiative cooling would draw heat away from the water, allowing it to freeze. Similarly, other societies constructed "cool roofs," employing reflective materials on their uppermost surfaces. These roofs acted to scatter incoming sunlight, significantly reducing the amount of heat absorbed by the building and thereby lowering interior temperatures. "People have taken advantage of this effect, either knowingly or unknowingly, for a very long time," remarks Aaswath Raman, a materials scientist at UCLA and a co-founder of SkyCool Systems, a pioneering startup in the field of radiative cooling.

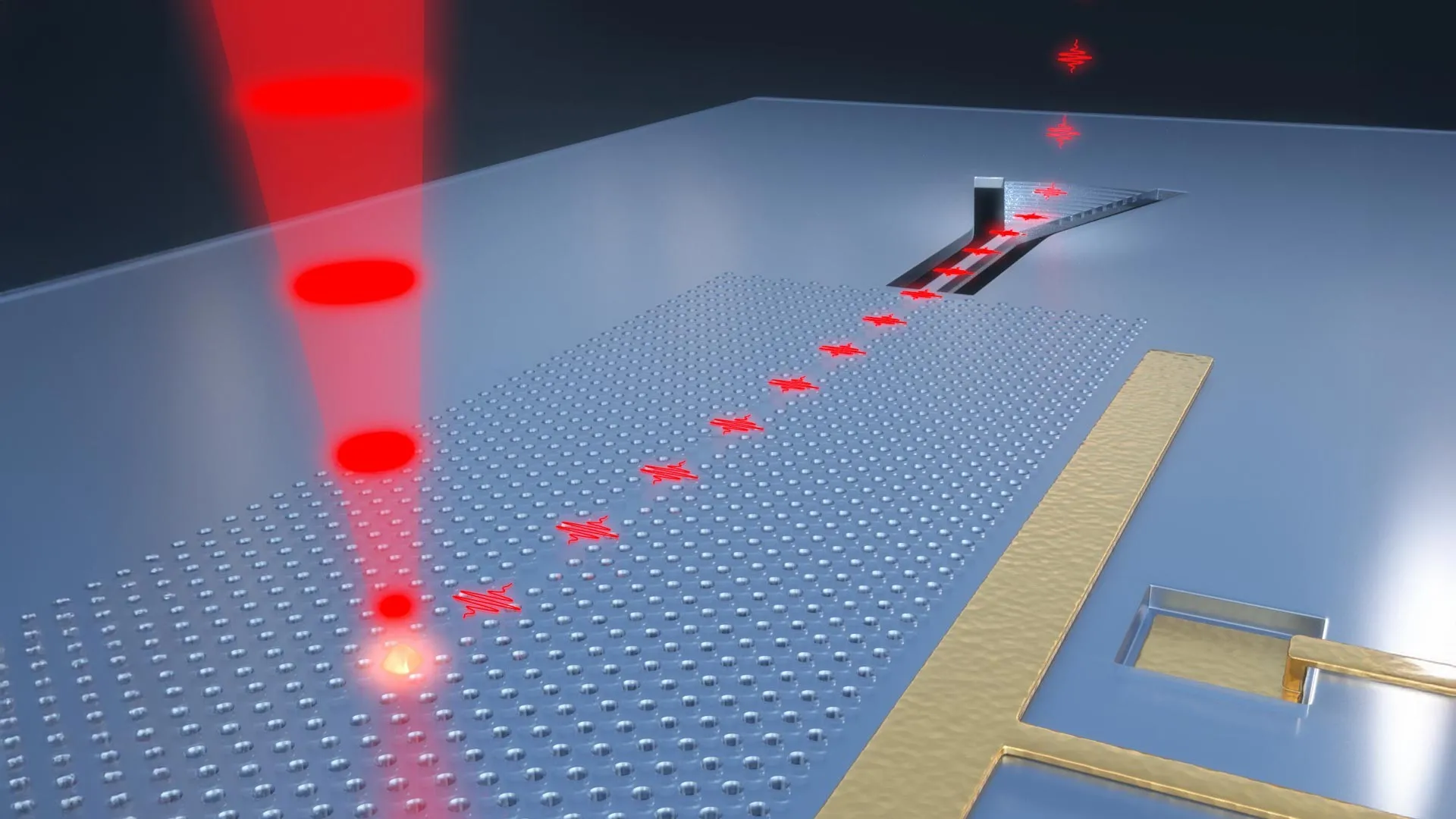

The advent of modern technology has propelled these ancient principles into a new era of sophisticated applications. Innovations are now being implemented in diverse settings, from the rooftops of California supermarkets to the architectural marvel of Japan’s Expo 2025 pavilion. Traditionally, surfaces exposed to direct sunlight would struggle to cool below the ambient air temperature. However, a breakthrough in 2014 by Raman and his research team demonstrated the potential for radiative cooling even during daylight hours. They engineered specialized photonic films designed to absorb incoming solar radiation and then re-emit heat at specific infrared wavelengths, falling within the crucial "atmospheric window"—a range of electromagnetic wavelengths between eight and 13 micrometers. This particular spectral band is significant because radiation within it can escape directly into space without being reabsorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere. These advanced films demonstrated the remarkable ability to dissipate heat effectively, even under intense sunlight, leading to a cooling effect of up to 9°F below ambient temperatures within buildings, all achieved without the need for air conditioning or any external energy source.

While the initial focus was on complex photonic structures, Raman notes that the industry has largely transitioned towards simpler, yet equally effective, sunlight-scattering materials. These now include ceramic cool roofs, advanced nanostructure coatings, and highly reflective polymers. These materials offer enhanced durability and scalability, making them more practical for widespread adoption. Their primary function is to divert a greater proportion of incident sunlight across a broad spectrum of wavelengths, thereby minimizing heat absorption.

The current landscape is characterized by a dynamic race among innovative startups, including SkyCool, Planck Energies, Spacecool, and i2Cool. These companies are striving to commercialize and mass-produce coatings capable of reflecting at least 94% of sunlight in most climatic conditions, and an impressive 97% or more in humid tropical environments. Early pilot projects have already yielded substantial cooling benefits for residential buildings, with documented reductions in air conditioning energy consumption ranging from 15% to 20%.

The potential applications of this technology extend far beyond passive cooling of buildings. Researchers are actively developing reflective textiles designed for personal wear, offering a vital layer of protection for individuals most vulnerable to extreme heat exposure. "This is personal thermal management," emphasizes Gan. "We can realize passive cooling in T-shirts, sportswear, and garments." This advancement promises to offer a direct and accessible means of mitigating heat stress for individuals working outdoors or living in regions with limited access to active cooling systems.

A thermal image captured during a SkyCool installation vividly illustrates the efficacy of these materials. Treated areas, depicted in white and yellow, are shown to be approximately 35°C cooler than the surrounding rooftop, demonstrating a significant temperature differential achieved through radiative cooling. This visual evidence underscores the tangible impact of these advanced coatings.

However, like all emerging technologies, radiative cooling solutions are not without their limitations and challenges. Their effectiveness, much like solar power generation, is inherently dependent on weather conditions. Cloud cover can impede the escape of reflected sunlight into space, diminishing the cooling effect. Accumulation of dust and atmospheric pollution can also dull the reflective surfaces, reducing their efficiency over time. Furthermore, many of the most durable and cost-effective coatings currently rely on Teflon and other fluoropolymers. These "forever chemicals," which do not biodegrade, pose a potential environmental risk. "They are the best class of products that tend to survive outdoors," acknowledges Raman. "So for long-term scale-up, can you do it without materials like those fluoropolymers and still maintain the durability and hit this low cost point?" This question highlights a critical area for ongoing research and development.

As with any proposed solution to the multifaceted challenges of climate change, it is crucial to maintain a balanced perspective. "We cannot be overoptimistic and say that radiative cooling can address all our future needs," states Gan. "We still need more efficient active air-conditioning." While a reflective roof is not a singular panacea for the global climate crisis, it represents a significant and promising advancement, offering a tangible and increasingly accessible method for making our world a cooler and more sustainable place. The ingenuity of combining ancient wisdom with modern scientific innovation is paving the way for a future where we can more effectively manage heat, reduce our reliance on energy-intensive cooling systems, and build more resilient communities in the face of a warming planet. The continued development and widespread adoption of these materials hold the potential to significantly mitigate the impacts of rising global temperatures, offering a much-needed respite from the intensifying heat.