Nilekani’s journey into the realm of digital transformation began nearly three decades ago. He masterminded Aadhaar, a system that has become the bedrock of India’s digital infrastructure. This system, which translates to "foundation" in Hindi, has enabled the development of a comprehensive suite of free, interoperable online tools. These tools span critical sectors such as government services, digital payments, banking, credit, and healthcare, offering unprecedented convenience and accessibility, even to those in the remotest corners of the country. Collectively, these systems are known as "digital public infrastructure" (DPI).

At 70 years old, many would expect Nilekani to be enjoying a well-deserved retirement. However, his mind is still brimming with groundbreaking ideas. He is actively involved in modernizing India’s often-unreliable electrical grid by integrating a digital communication layer to enhance its stability. Simultaneously, he is championing the global expansion of DPI’s financial capabilities, envisioning a "finternet" that will serve as a universal digital conduit for economic transactions. "It sounds like some crazy stuff," Nilekani admits, "But I think these are all big ideas, which over the next five years will have demonstrable, material impact." He sees this as a fitting capstone to his public career: to "Aadhaarize the world."

India’s digital backbone, largely conceptualized and implemented under Nilekani’s guidance, has revolutionized daily life for millions. A farmer in a remote village, miles from the nearest bank, can now receive welfare payments or transfer money with a simple fingerprint scan at a local store. Essential documents like driver’s licenses, birth certificates, and educational records are available digitally through a smartphone-based wallet. In urban centers, cash is rapidly becoming obsolete, with mobile payments seamlessly facilitating transactions from high-street retail to roadside vendors. The Unified Payments Interface (UPI), a key component of DPI, has eliminated transaction fees and ensured interoperability between all payment apps and bank accounts. Even the healthcare sector is undergoing a digital overhaul, with public and private hospitals digitizing medical records onto a national platform. The Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) is fostering a more equitable online marketplace, enabling consumers to search for products across various platforms and liberating small merchants from the dominance of e-commerce giants.

The linchpin of these advancements is Aadhaar. This 12-digit unique identification number, coupled with biometric authentication (fingerprint or iris scan) or an SMS code, grants access to a myriad of services, including government benefits, SIM cards, bank accounts, and digital signatures. The Indian government estimates that Aadhaar has saved trillions of rupees by enhancing efficiency, curbing corruption, and preventing fraud. While the system has faced scrutiny regarding privacy and security concerns inherent in managing a database of 1.4 billion individuals, it has undeniably brought a significant portion of bureaucratic interactions into the digital realm for the world’s most populous nation. Nilekani, who marshaled a vast network of civil servants, tech companies, and volunteers to bring these innovations to life, finds immense satisfaction in witnessing their tangible impact on people’s lives.

Despite approaching the twilight of his career, Nilekani remains actively engaged. He serves as the "chief mentor" for the India Energy Stack (IES), an initiative aimed at unifying data from various entities within the power sector. IES seeks to assign unique digital identities to power plants, storage facilities, and even decentralized energy sources like rooftop solar panels and electric vehicles. By standardizing data formats and utilizing open protocols, IES aims to provide grid operators with real-time insights into energy supply and demand, while also simplifying grid connectivity for individuals.

Nilekani’s most ambitious endeavor is his concept of a global "finternet." This initiative integrates Aadhaar’s principles with blockchain technology to create digital tokens representing not only financial assets like stocks and bonds but also real-world assets such as property and jewelry. This system is designed to empower individuals, particularly those in underserved populations, to trade their assets or use them as collateral for loans, thereby expanding financial inclusion on a global scale. The finternet project has garnered support from 30 partners across four continents and is slated for launch next year.

Born in Bengaluru in 1955 to a middle-class family with a strong sense of social responsibility, Nilekani’s upbringing was influenced by the socialist ideals of India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. After earning an electrical engineering degree from the Indian Institute of Technology, he co-founded Infosys in 1981, a company that played a pivotal role in establishing India as a global IT outsourcing hub. In 1999, he participated in a government task force focused on upgrading Bengaluru’s infrastructure. Initially hesitant to be perceived as a mere techno-optimist, Nilekani’s perspective shifted as he witnessed the deep-seated issues of bureaucratic inefficiency, corruption, and financial exclusion that plagued India. His 2008 book, Imagining India: The Idea of a Renewed Nation, became a manifesto for a networked, future-ready India.

This vision caught the attention of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who tasked Nilekani with realizing a national identity card project. Nilekani’s team made the pivotal, albeit controversial, decision to employ biometrics. This approach, utilizing fingerprints and iris scans, aimed to prevent duplicate registrations and eliminate the need for physical documentation. The undertaking was akin to fast-forwarding through industrialization, requiring a massive data collection effort and sophisticated infrastructure capable of matching new enrollments against hundreds of millions of existing records in near real-time. The Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), responsible for Aadhaar, registered over a million new users daily at its peak, with a lean technical team of approximately 50 developers and a budget of less than half a billion dollars. Building on this success, Nilekani and his colleagues began exploring other societal challenges amenable to their digital-first approach. "We built more and more layers of capability," Nilekani remarked, "and then this became a wider-ranging idea. More grandiose."

Unlike other nations that opted for state-controlled digital infrastructures (like China) or public-private partnerships prioritizing profit (like the US), Nilekani envisioned a different model for India. He advocated for open and interoperable critical technologies in identity, payments, and data sharing, preventing monopolization by either the state or private entities. Consequently, DPI’s components utilize open standards and APIs, allowing anyone to integrate with the system, thus avoiding "walled gardens" controlled by any single entity.

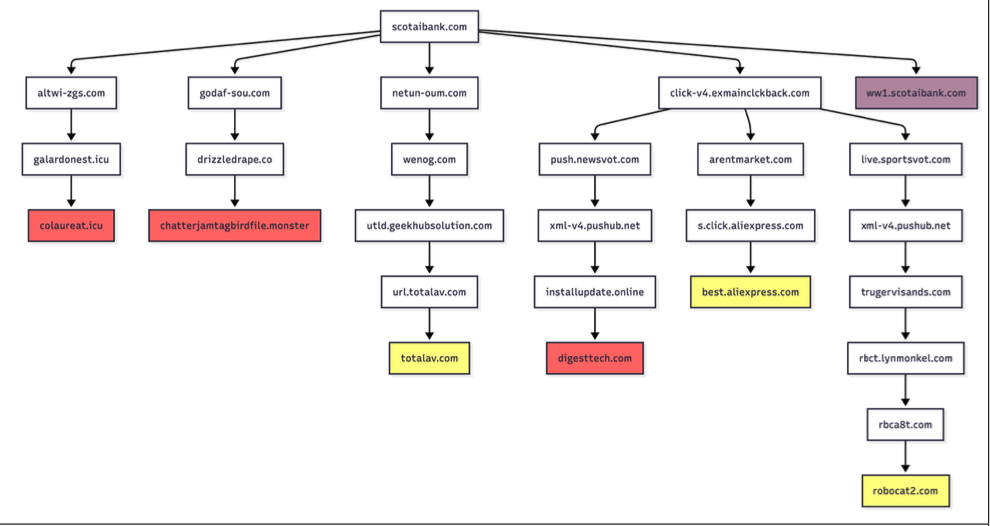

The implementation of extensive digital databases for financial and governmental services has raised valid concerns about personal liberty and potential surveillance. Aadhaar, in particular, has been a target for privacy advocates. While the government maintains that an Aadhaar number is meaningless without biometric or SMS authentication, and citing the lack of evidence of harm from disclosure, critics point to instances where the system’s vulnerabilities have been exploited. Reports of Aadhaar data breaches, including one in 2023 where hackers allegedly offered over 800 million Indians’ records on the dark web, have eroded public trust.

A significant loophole arises from the common practice of users relying on the physical Aadhaar card, an officially-looking document often used as proof of identity, rather than the secure digital authentication methods. The lack of an expiration date on these cards allows for the creation of multiple valid cards with altered personal details, a practice that raises concerns about identity fraud. A 2018 NGO report indicated that a substantial percentage of individuals using Aadhaar for bank account openings relied on this document over digital authentication, a statistic that has not been updated since, leaving the current prevalence of the issue unknown. Activists lament the lack of transparency and robust data collection regarding such vulnerabilities.

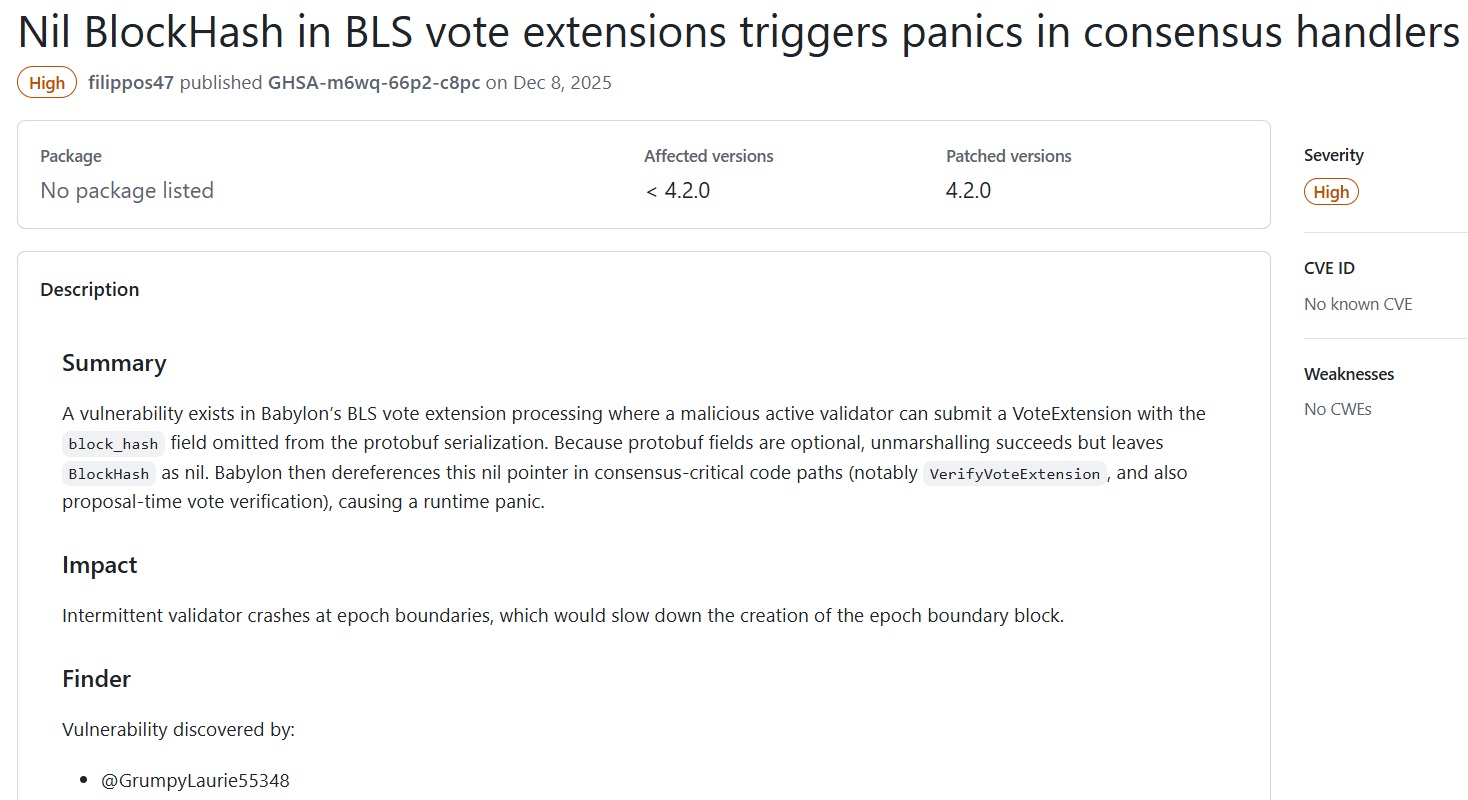

Furthermore, technical flaws in Aadhaar’s biometric technology have reportedly led to individuals being denied essential government services. While the government downplays these risks, the UIDAI’s reluctance to disclose specific numbers makes it difficult to ascertain the true extent of the problem. Advocates call for greater transparency and systematic examination of these exclusionary instances. Despite the ambition for open and interoperable tools, the benefits have not uniformly reached all segments of the population, particularly rural and impoverished communities. The dominance of large e-commerce companies persists, and the growth of ONDC has shown a decline since 2024. While DPI services boast hundreds of millions of users, a significant portion of India’s population remains unreached.

Nilekani, typically composed, expresses frustration at these criticisms, asserting that they often overlook the systemic dysfunctions that necessitated these digital interventions. He remains resolute that technology was the only viable path forward for a nation of 1.4 billion. "How do you move a country of 1.4 billion people?" he poses. "There’s no other way you can fix it."

He points to tangible evidence of success: over 500 million basic bank accounts opened through Aadhaar, bringing millions into the formal financial system. India’s Unified Payments Interface has surpassed Visa as the world’s largest real-time payments system. "There is no way Aadhaar could have worked but for the fact that people needed this thing," Nilekani asserts. "There’s no way payments would have worked without people needing it. So the voice of the people—they’re voting with their feet."

This demonstrable need is not confined to India. "Many countries don’t have a proper birth registration system. Many countries don’t have a payment system. Many countries don’t have a way for data to be leveraged," Nilekani observes, underscoring the global applicability of DPI. Foreign governments frequently dispatch delegations to study India’s DPI models. International organizations like the World Bank and the United Nations are promoting the concept in developing nations eager for digital advancement. The Gates Foundation actively supports digital infrastructure projects, and Nilekani has established and funded a network of think tanks and NGOs dedicated to "propagating the gospel" of DPI.

Nilekani acknowledges that he may not witness the full global realization of DPI during his lifetime. He frames this as a race against time, both personally and for India. He expresses concern that India’s vast young population, its "demographic dividend," could devolve into a "demographic disaster" if economic opportunities are not created at scale. Despite rapid growth, the benefits have been unevenly distributed, with persistently high youth unemployment posing a significant challenge in an economically volatile nation.

"Maybe I’m a junkie," he admits, reflecting on his continued drive. "Why the hell am I doing all this? I think I need it. I think I need to keep curious and alive and looking at the future." However, the very nature of building the future is that it remains perpetually in progress, a continuous unfolding.