The venerable Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a titan of scientific discovery nestled beneath the Swiss-French border, is poised for an extended shutdown. This hiatus, commencing in June, is not a permanent retirement but a strategic pause for a transformative upgrade designed to dramatically enhance its capabilities. Simultaneously, the global scientific community is actively contemplating the LHC’s eventual successor, a next-generation atom smasher that promises to push the boundaries of human knowledge even further into the mysteries of the universe. This period marks a pivotal moment for CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, and indeed for the entire field of particle physics, as it prepares for a new era of exploration and discovery.

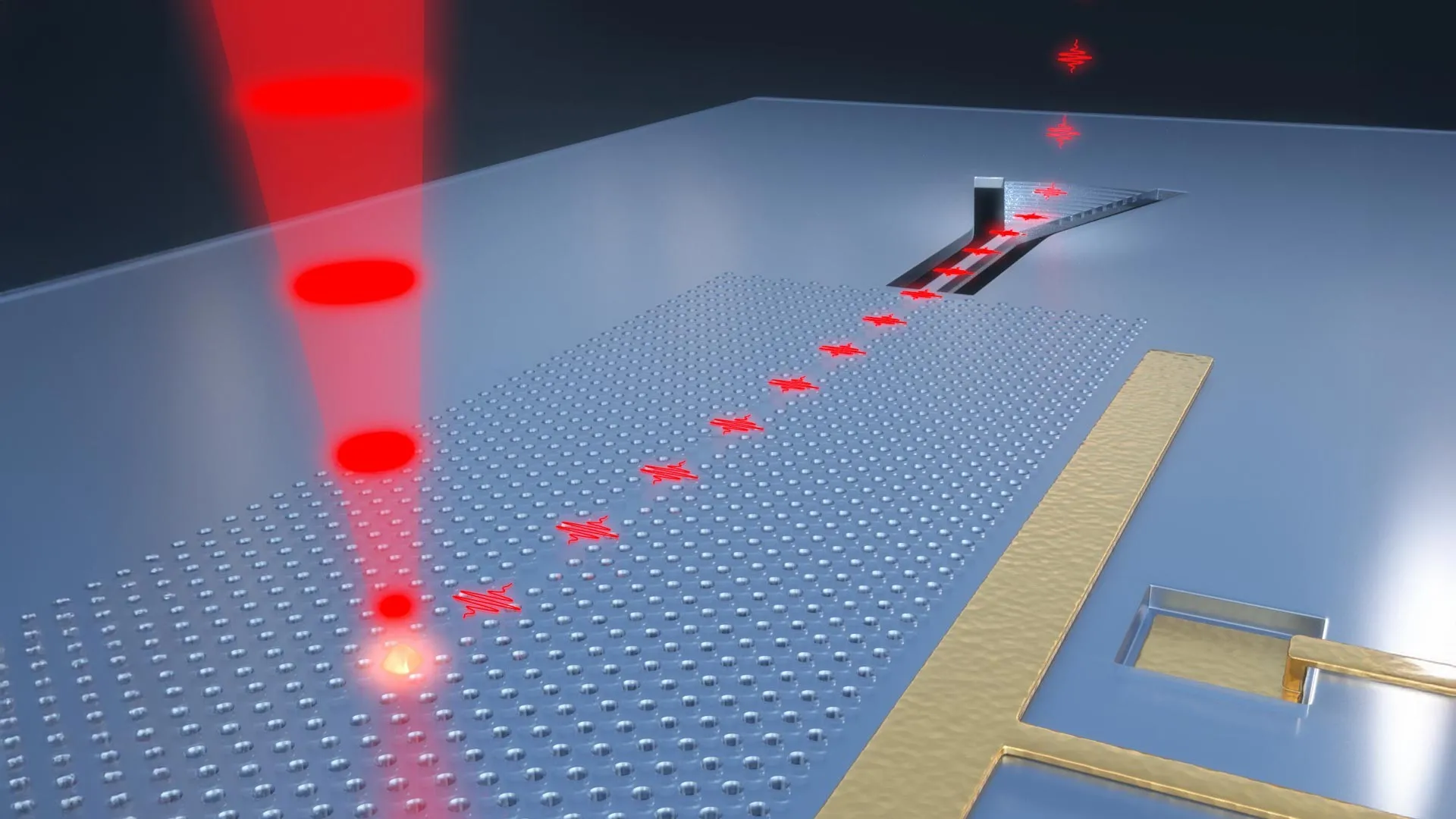

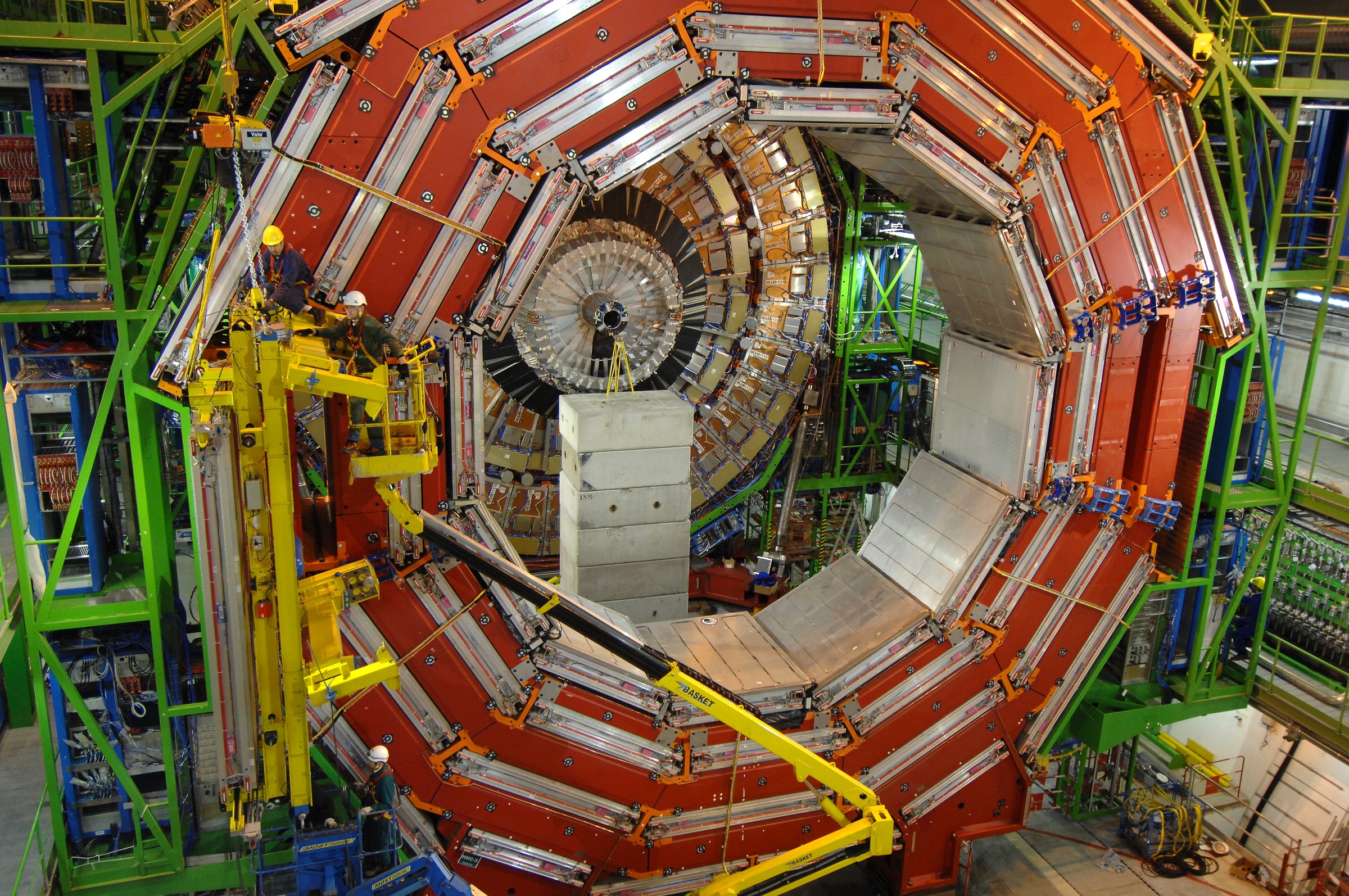

The LHC, an colossal 16-mile (27-kilometer) ring-shaped tunnel, has been instrumental in replicating the extreme conditions that existed just moments after the Big Bang. By accelerating protons and heavy ions to nearly the speed of light and then smashing them together, physicists delve into a realm where the laws of physics become exquisitely strange and counterintuitive. Its most celebrated achievement came in 2012 with the confirmed discovery of the Higgs boson, an elementary particle that had eluded detection for decades. This particle, through its incredibly esoteric quantum properties and interaction with the omnipresent Higgs field, is fundamentally responsible for endowing all other fundamental particles with their mass. The discovery of the Higgs boson was not merely a scientific triumph; it completed the Standard Model of particle physics, the most comprehensive theory describing the fundamental forces and particles that make up our universe, earning the Nobel Prize in Physics for Peter Higgs and François Englert.

Beyond the Higgs, the LHC has been a prolific engine of research. It has meticulously studied the properties of the Higgs boson itself, confirming its spin and parity, and probing its interactions with other particles. Physicists have also utilized the LHC to create and study quark-gluon plasma, a state of matter thought to have existed fractions of a second after the Big Bang, where quarks and gluons are deconfined. This "mini-Big Bang" research offers insights into the strong nuclear force and the early universe. Furthermore, the LHC has been on a relentless quest for physics beyond the Standard Model, searching for exotic particles and phenomena that could explain enduring cosmic puzzles like dark matter and dark energy. While definitive proof of supersymmetry (SUSY) or extra dimensions remains elusive, the LHC has significantly constrained theoretical models, narrowing the search space for future experiments. The collider has also contributed to precision measurements of known particles, refining our understanding of their fundamental properties and interactions. The LHC is a testament to international collaboration, with thousands of scientists and engineers from around the globe contributing to its design, operation, and data analysis.

Even an instrument responsible for one of the most profound scientific breakthroughs in history requires periodic enhancements to remain at the cutting edge. The upcoming five-year shutdown is dedicated to a monumental undertaking: the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) upgrade. Luminosity, in the context of particle accelerators, refers to the number of particle collisions per unit of time and area. By increasing the luminosity tenfold, the HL-LHC will produce a significantly larger dataset, allowing for an exponential increase in the number of experiments that can be conducted. This will provide physicists with unprecedented statistical power to observe rare events, make more precise measurements, and increase their sensitivity to potential new particles or interactions.

The HL-LHC project involves a comprehensive overhaul of key components within the accelerator complex. This includes installing new, more powerful superconducting magnets, particularly "crab cavities" which tilt the proton bunches to maximize overlap during collisions, and improved focusing systems to squeeze the particle beams into incredibly dense packets. The upgrade also necessitates enhancing the detectors themselves – ATLAS and CMS, the two largest experiments – to handle the increased data rates and higher radiation levels. The engineering challenges are immense, requiring meticulous planning and execution to integrate these advanced technologies into the existing infrastructure. While the five-year downtime, with the HL-LHC not expected to be operational again until mid-2030, represents a substantial pause in active data collection, it is an investment deemed absolutely essential for the next generation of discoveries.

Rest assured, the LHC will not go dark without leaving physicists with an immense amount of "homework" to complete before its glorious return. As Mark Thomson, the newly appointed Director-General of CERN, who commenced his term on New Year’s Day, affirmed to The Guardian, "The machine is running brilliantly and we’re recording huge amounts of data. There’s going to be plenty to analyze over the period. The physics results will keep on coming." This period of intense data analysis will allow researchers to meticulously scrutinize the existing troves of information, potentially unearthing subtle signals or unexpected correlations that could point towards new physics. Furthermore, the shutdown provides an invaluable opportunity for detector maintenance, upgrades, and the development of sophisticated new analysis techniques and theoretical models that will be crucial for interpreting the forthcoming deluge of HL-LHC data. Thomson, a professor of experimental particle physics at the University of Cambridge, expressed his enthusiasm for this transformative phase, stating, "It’s an incredibly exciting project. It’s more interesting than just sitting here with the machine hammering away." His leadership during this crucial upgrade phase underscores CERN’s commitment to long-term vision and innovation.

Beyond the HL-LHC, CERN is already looking ahead to the LHC’s ultimate successor, a truly gargantuan machine designed to push the energy and precision frontiers even further. The leading candidate is the Future Circular Collider (FCC), a proposed ring with an astounding circumference of 56 miles (90 kilometers), dwarfing the LHC. The FCC concept envisions a phased construction. The first stage, planned for the late 2040s, would operate as an electron-positron collider, acting as a high-precision "Higgs factory" to meticulously study the properties of the Higgs boson in unprecedented detail. This would provide crucial insights into its interactions and potential connections to new physics. The second stage, slated for the 2070s, would then transform the tunnel into a proton-proton collider, capable of accelerating protons to energies far exceeding those of the LHC, enabling a deeper probe into the fundamental forces and potentially unveiling entirely new particles and interactions.

The scientific potential of the FCC is immense. It could provide definitive answers to questions about dark matter, dark energy, and the very fabric of spacetime. However, the project comes with an equally immense price tag, estimated at nearly $19 billion, a sum too large for CERN to shoulder independently. This financial hurdle necessitates broad international collaboration and significant political will. Furthermore, the scientific community grapples with fundamental questions about the optimal path forward. There’s an ongoing debate about whether increasingly larger and more expensive particle accelerators represent the most efficient way to address some of the biggest questions in science, such as the nature of dark matter and dark energy. Some argue for diversifying research investments into astrophysical observations, quantum gravity theories, or smaller, specialized experiments.

Despite these challenges and debates, Mark Thomson remains a staunch believer in the power of large atom smashers. He articulated this conviction to The Guardian, stating, "We’ve not got to the point where we have stopped making discoveries and the FCC is the natural progression. Our goal is to understand the universe at its most fundamental level. And this is absolutely not the time to give up." His statement encapsulates the enduring human drive to explore the unknown, to push the boundaries of what is conceivable, and to seek fundamental truths about our existence. The pursuit of such knowledge often leads to unexpected technological spin-offs and inspires generations of scientists and engineers, making the investment in "big science" not just about fundamental physics, but also about societal progress.

As the LHC enters its crucial upgrade phase, the global scientific community stands on the cusp of a new era of discovery. The High-Luminosity LHC promises to unlock further secrets of the universe, providing a clearer window into the workings of fundamental particles and forces. Simultaneously, the visionary plans for the Future Circular Collider underscore humanity’s relentless ambition to reach even higher energies and greater precision in its quest to understand the cosmos. This journey, from the current LHC to its upgraded form and the potential successor, is a testament to scientific ingenuity, international cooperation, and the unyielding human desire to comprehend the universe at its most profound level. It is, unequivocally, not the time to give up.