The global mental health crisis, marked by over a billion individuals suffering from conditions like anxiety and depression, particularly among the youth, and hundreds of thousands of annual suicides, has spurred a search for accessible and affordable solutions. Artificial intelligence has emerged as a potent, albeit controversial, contender in this landscape. Millions are already engaging with AI chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Anthropic’s Claude for therapeutic purposes, alongside specialized applications like Wysa and Woebot. Concurrently, researchers are investigating AI’s potential to monitor well-being through wearables, analyze vast clinical datasets for novel insights, and alleviate burnout among human mental health professionals.

However, this nascent field has yielded a spectrum of outcomes. While many have discovered solace and even experienced promise in AI therapists, others have been led into delusional states or, more tragically, have been linked to suicides, resulting in lawsuits against AI companies. OpenAI’s CEO, Sam Altman, revealed that a significant portion of ChatGPT users—approximately 0.15%—engage in conversations indicating potential suicidal ideation, translating to roughly a million individuals weekly sharing such thoughts with this single platform. The year 2025 has been pivotal, bringing to the forefront the tangible consequences of AI therapy, the fragility of AI guardrails, and the inherent risks of entrusting sensitive personal data to corporations driven by profit motives. This disorienting period, characterized by breakthroughs, scandals, and confusion, is deeply rooted in historical narratives of care, technology, and trust, as explored by several timely books.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are often referred to as "black boxes" due to the inscrutability of their output generation, stemming from their complex algorithms and immense training data. Similarly, the human mind, particularly in states of distress, is frequently described as a "black box" by mental health professionals, highlighting the inherent difficulty in understanding the precise origins of suffering. The convergence of these two "black boxes"—the AI and the human psyche—creates unpredictable feedback loops that can further obscure the causes of mental health struggles and their potential solutions. While contemporary anxieties are fueled by rapid AI advancements, they also echo the cautionary sentiments of pioneers like MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum, who questioned the efficacy and ethics of computerized therapy as early as the 1960s.

Charlotte Blease, a philosopher of medicine, presents an optimistic perspective in her book, Dr. Bot: Why Doctors Can Fail Us—and How AI Could Save Lives. Blease explores the potential positive impacts of AI across various medical domains, acknowledging risks while suggesting that AI models can alleviate both patient suffering and medical burnout. She posits that crumbling health systems, doctor shortages, and long waiting times create fertile ground for errors and patient frustration. Blease believes AI can not only ease the burden on medical professionals but also bridge the gap between patients and caregivers, particularly for those intimidated by or fearful of judgment from human providers, especially concerning mental health challenges. However, she is acutely aware of the drawbacks, citing a 2025 study highlighting the potential for inconsistent and dangerous AI responses, alongside privacy concerns, as AI companies are not bound by the same confidentiality standards as licensed therapists. Blease’s personal experiences, including the prolonged diagnostic journey of siblings with muscular dystrophy and the loss of her partner and father, inform her nuanced view, acknowledging both the brilliance of human care and its potential failures.

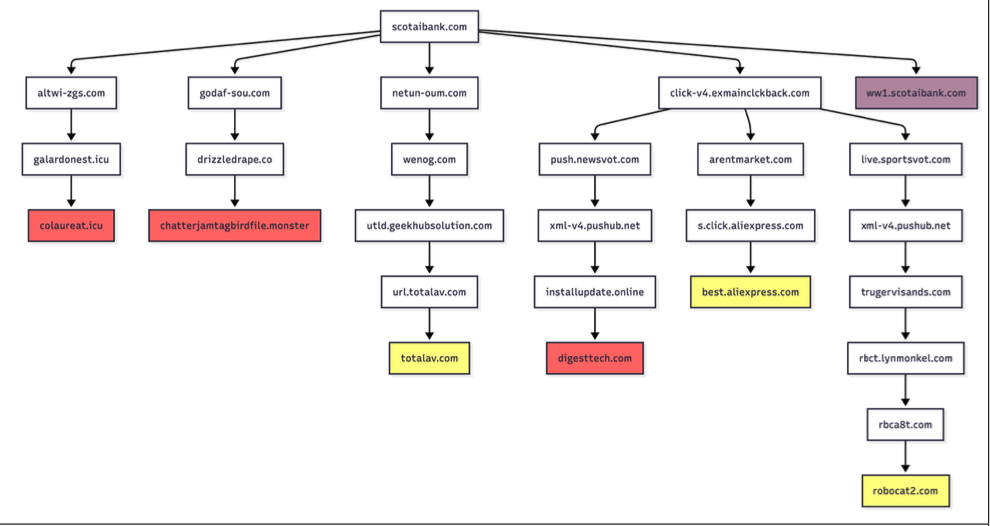

Daniel Oberhaus’s The Silicon Shrink: How Artificial Intelligence Made the World an Asylum delves into similar complexities, beginning with the tragic suicide of his younger sister. While navigating her digital footprint, Oberhaus contemplated whether technology could have offered support for her lifelong psychiatric struggles. He envisioned a scenario where her personal data might have provided crucial insights for her mental health providers, or where algorithms could have detected distress and triggered timely interventions. This concept of digital phenotyping—mining digital behavior for clues about mental state—appears elegant but raises profound ethical questions when integrated into psychiatric artificial intelligence (PAI). Oberhaus contends that PAI, far beyond chatbot therapy, risks exacerbating existing psychiatric challenges by imposing a veneer of precision onto a field fundamentally uncertain about the causes of mental illness. He likens PAI to "grafting physics onto astrology," suggesting that while digital data might be precise, its application within a field like psychiatry, based on less certain foundations, is problematic. Oberhaus coins the term "swipe psychiatry" to describe the outsourcing of clinical decisions to LLMs based on behavioral data, arguing that this approach fails to address fundamental psychiatric issues and could lead to the atrophy of human therapists’ skills. He draws parallels between PAI and historical asylums, where institutionalized patients lost autonomy, envisioning a more insidious digital captivity. Users surrendering privacy to AI chatbots contribute to a surveillance economy, where complex inner lives are commodified. Oberhaus warns that PAI could flatten human experience into predictable patterns, sacrificing individualized care and leading to a future where individuals are confined within an "algorithmic asylum," omnipresent and inescapable.

Eoin Fullam’s Chatbot Therapy: A Critical Analysis of AI Mental Health Treatment echoes these concerns, offering an academic examination of the assumptions underlying AI chatbot therapy and the potential for capitalist incentives to corrupt these tools. Fullam notes that the pursuit of market dominance often prioritizes company interests over user welfare. While he doesn’t claim therapy-bot creators will inevitably act nefariously, he highlights the inherent tension between the drive to profit and the goal of healing. In this paradigm, exploitation and therapy become intertwined: each digital session generates data that fuels a profitable system, where unpaid users seeking care are simultaneously exploited. The more effective the therapy appears, the more entrenched this cycle becomes, blurring the lines between genuine care and commodification. Fullam concludes that the more users benefit from AI therapy, the more they are subjected to exploitation.

This cyclical dynamic, akin to an ouroboros, serves as a central metaphor in Fred Lunzer’s debut novel, Sike. The novel follows Adrian, a ghostwriter of rap lyrics, and his relationship with Maquie, a business professional adept at identifying emerging technologies. Adrian utilizes "Sike," a commercial AI therapist embedded in smart glasses, to manage his anxieties. Sike meticulously analyzes a user’s "vitals"—including gait, eye contact, speech patterns, and even physiological functions—creating a comprehensive digital profile. Lunzer positions Sike as a luxury product, accessible only to the affluent, and explores its impact on the well-being of the privileged, portraying a boutique version of Oberhaus’s digital asylum. While the novel touches upon a "Japanese torture egg," it largely sidesteps the broader dystopian implications of its subject matter, focusing instead on the social interactions of the wealthy. The creator of Sike is portrayed as a benevolent figure with a grand vision, yet the anticipated dystopian turn never fully materializes, leaving the reader with a sense of unresolved unease.

The sudden proliferation of AI therapists, both in reality and fiction, feels remarkably futuristic, as if it belongs to an era of self-cleaning streets and pneumatic tube travel. However, this convergence of mental health and artificial intelligence has been developing for decades. Carl Sagan, the astronomer, envisioned a "network of computer psychotherapeutic terminals" to address the growing demand for mental health services. Frank Rosenblatt, a psychologist, developed the Perceptron, an early neural network, in 1958. The potential of AI in mental health was recognized by the 1960s, leading to early computerized psychotherapists like the DOCTOR script within Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA chatbot. Weizenbaum, deeply concerned about computerized therapy, argued in his 1976 book, Computer Power and Human Reason, that while computers might make psychiatric judgments, they "ought not to be given such tasks." His caution resonates as AI therapists emerge at scale, playing out a familiar dynamic: tools with ostensibly good intentions become enmeshed in systems that can exploit, surveil, and reshape human behavior. In the urgent pursuit of mental health support, the advent of AI may inadvertently close doors for those in need.