This pioneering prosthetic eye device, named PRIMA and meticulously developed at Stanford Medicine, stands as the first of its kind to successfully restore usable vision to those afflicted with otherwise untreatable vision loss. The technology’s profound impact lies in its ability to enable patients to perceive shapes and patterns, a level of visual perception referred to as "form vision." Dr. Daniel Palanker, a distinguished professor of ophthalmology and a co-senior author of the study, emphasized the historical significance of this achievement. "All previous attempts to provide vision with prosthetic devices resulted in basically light sensitivity, not really form vision," he stated. "We are the first to provide form vision." The international research effort was co-led by Dr. José-Alain Sahel, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, with Dr. Frank Holz of the University of Bonn in Germany serving as the lead author, highlighting the global collaborative spirit behind this breakthrough.

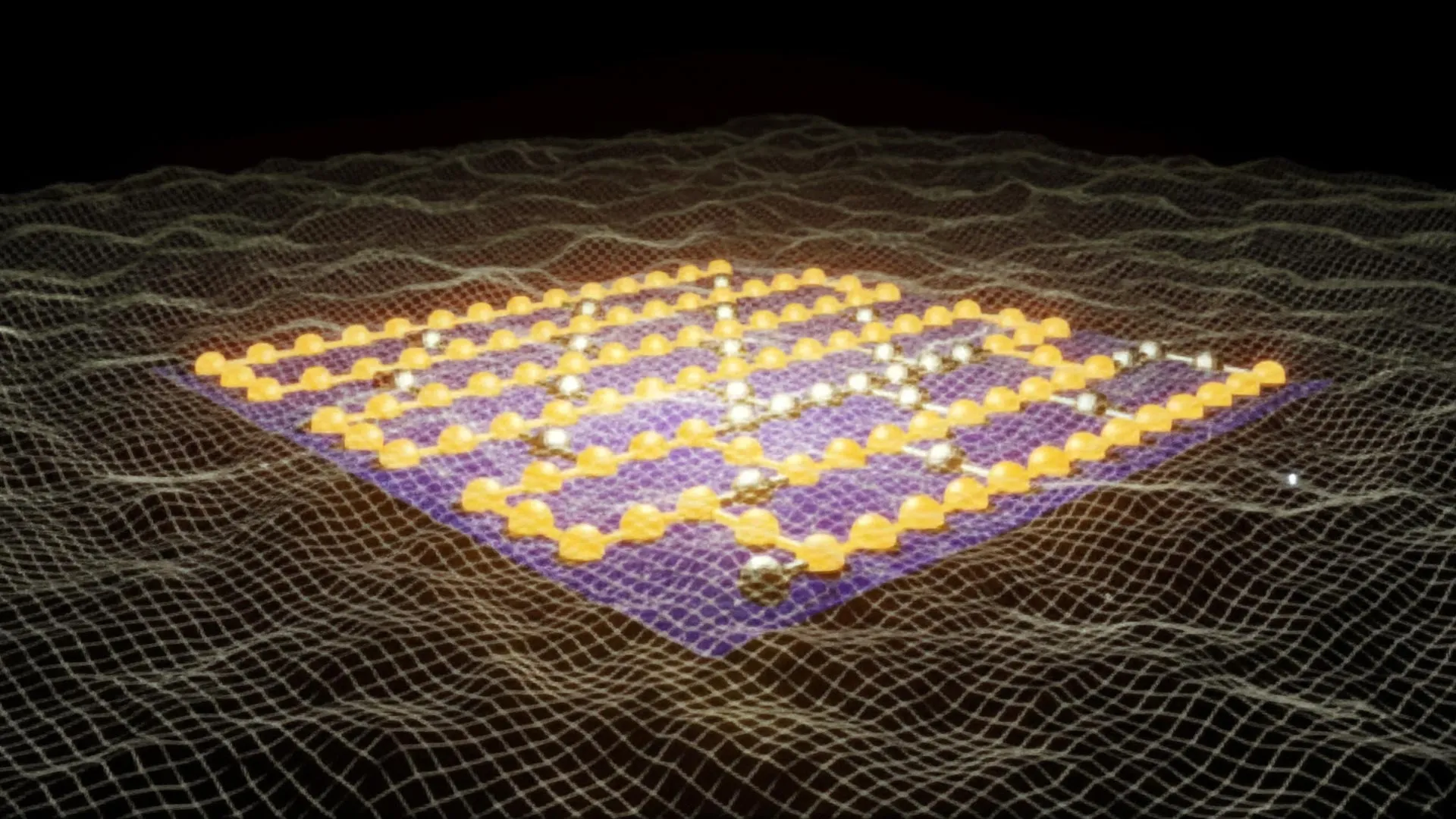

The sophisticated PRIMA system operates through a synergistic combination of two key components: a compact camera integrated into a pair of advanced smart glasses, and a state-of-the-art wireless chip surgically implanted within the retina. The camera meticulously captures visual information from the external environment and then transmits this data as infrared light to the retinal implant. Upon receiving this infrared projection, the chip ingeniously converts the light signals into electrical impulses. These generated electrical signals then serve as a direct replacement for the damaged photoreceptor cells – the light-sensing cells in the retina responsible for detecting light and transmitting visual data to the brain. In essence, the PRIMA system bypasses the defunct photoreceptors and directly stimulates the remaining intact retinal neurons, thereby reconstructing a visual pathway to the brain.

The development of the PRIMA project is the culmination of decades of dedicated scientific endeavor, involving extensive research, the creation of numerous prototypes, rigorous animal testing, and ultimately, a successful initial human trial. Dr. Palanker’s initial inspiration for this revolutionary technology dates back two decades, stemming from his work with ophthalmic lasers aimed at treating various eye disorders. "I realized we should use the fact that the eye is transparent and deliver information by light," he recalled. His vision, first conceptualized in 2005, has now materialized into a device that is performing remarkably well in patients.

Participants in the latest clinical trial were individuals diagnosed with an advanced stage of age-related macular degeneration, specifically geographic atrophy. This debilitating condition progressively destroys central vision, a severe form of AMD that affects over 5 million people worldwide and is the leading cause of irreversible blindness in older adults. In macular degeneration, the crucial light-sensitive photoreceptor cells located in the central retina deteriorate, leaving individuals with severely limited or absent central vision, often retaining only peripheral vision. Crucially, however, many of the retinal neurons responsible for processing visual information often remain functional. The PRIMA system masterfully capitalizes on these surviving neural structures, offering a lifeline to patients who would otherwise face a lifetime of profound vision impairment.

The implant itself is remarkably small, measuring a mere 2 by 2 millimeters, and is strategically placed in the area of the retina where photoreceptor cells have been lost. A key differentiator of the PRIMA chip is its unique response to infrared light, unlike natural photoreceptors which are stimulated by visible light. This allows the chip to function independently of the remaining functional photoreceptors in the periphery. "The projection is done by infrared because we want to make sure it’s invisible to the remaining photoreceptors outside the implant," explained Dr. Palanker, underscoring the precise engineering involved to avoid interference and maximize the integration of artificial and natural vision.

This innovative design enables patients to simultaneously utilize both their natural peripheral vision and the newly restored prosthetic central vision. This dual-vision capability significantly enhances their ability to orient themselves in their environment and navigate safely. "The fact that they see simultaneously prosthetic and peripheral vision is important because they can merge and use vision to its fullest," Dr. Palanker noted, highlighting the synergistic benefits of combining artificial and biological visual input. Furthermore, the PRIMA implant is photovoltaic, meaning it generates its own electrical current solely from light. This intrinsic power generation allows it to operate wirelessly and be safely implanted beneath the retina, eliminating the need for external power sources or invasive cables that characterized earlier artificial eye technologies.

The success of the PRIMA system is vividly illustrated by the participants’ renewed ability to read. The recent trial enrolled 38 patients, all over the age of 60, who had geographic atrophy due to AMD and experienced visual acuity worse than 20/320 in at least one eye. Following the implantation of the chip in one eye, patients began using the smart glasses four to five weeks later. While some individuals could discern patterns immediately after starting the training, all participants demonstrated consistent improvements in their visual acuity over the ensuing months. Dr. Palanker likened the rehabilitation process to that of cochlear implants, stating, "It may take several months of training to reach top performance – which is similar to what cochlear implants require to master prosthetic hearing."

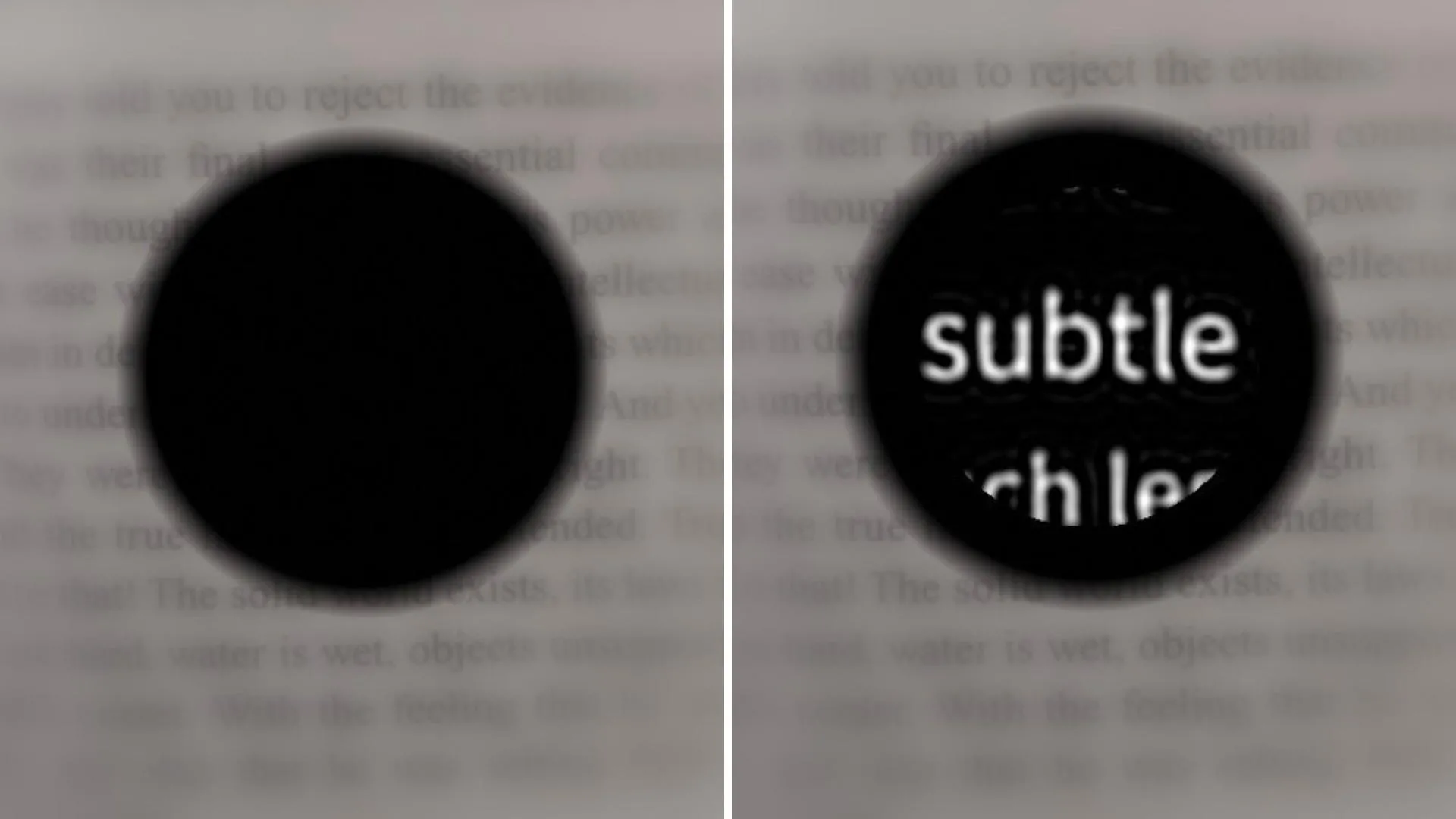

The results are compelling: of the 32 patients who successfully completed the one-year trial, a remarkable 27 could read again. Furthermore, 26 participants exhibited a clinically meaningful improvement in their visual acuity, defined as the ability to read at least two additional lines on a standard eye chart. On average, participants experienced an improvement of 5 lines on the eye chart, with one individual demonstrating an extraordinary improvement of 12 lines. The participants actively integrated the prosthesis into their daily lives, using it to read books, decipher food labels, and navigate public transportation by reading subway signs. The smart glasses provided crucial functionality, allowing users to adjust contrast and brightness, and magnify text up to 12 times. The user satisfaction was also notably high, with two-thirds of participants reporting medium to high levels of satisfaction with the device. While side effects were reported by 19 participants, including ocular hypertension, tears in the peripheral retina, and subretinal hemorrhage, these were generally non-life-threatening and resolved within approximately two months, underscoring the overall safety profile of the implant.

Looking towards the future, the PRIMA device, in its current iteration, provides black-and-white vision without intermediate shades. However, Dr. Palanker is actively developing software to introduce a full range of grayscale vision. "Number one on the patients’ wish list is reading, but number two, very close behind, is face recognition," he revealed. "And face recognition requires grayscale." This advancement will significantly enhance social interaction and recognition capabilities for users. Beyond grayscale, Dr. Palanker is also engineering chips with higher resolution. The current resolution is limited by the size of the pixels on the chip, which are 100 microns wide, with 378 pixels per chip. A new version, already tested in rats, aims to incorporate pixels as small as 20 microns wide, boasting an impressive 10,000 pixels per chip. This substantial increase in pixel density is expected to dramatically improve visual clarity.

Dr. Palanker also expressed his enthusiasm for testing the device’s efficacy in treating other forms of blindness caused by photoreceptor loss. He reiterated that the current chip represents the first generation and that future iterations will offer superior resolution. "The next generation of the chip, with smaller pixels, will have better resolution and be paired with sleeker-looking glasses," he stated. Projections indicate that a chip with 20-micron pixels could potentially restore a patient’s vision to 20/80, with the added benefit of electronic zoom potentially enabling them to achieve near 20/20 vision.

The groundbreaking research involved a vast network of esteemed institutions and researchers from around the globe, including the University of Bonn, Germany; Hôpital Fondation A. de Rothschild, France; Moorfields Eye Hospital and University College London; Ludwigshafen Academic Teaching Hospital; University of Rome Tor Vergata; Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, University of Lübeck; L’Hôpital Universitaire de la Croix-Rousse and Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1; Azienda Ospedaliera San Giovanni Addolorata; Centre Monticelli Paradis and L’Université d’Aix-Marseille; Intercommunal Hospital of Créteil and Henri Mondor Hospital; Knappschaft Hospital Saar; Nantes University; University Eye Hospital Tübingen; University of Münster Medical Center; Bordeaux University Hospital; Hôpital National des 15-20; Erasmus University Medical Center; University of Ulm; Science Corp.; University of California, San Francisco; University of Washington; University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; and Sorbonne Université. The study received crucial financial support from Science Corp., the National Institute for Health and Care Research, Moorfields Eye Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust, and University College London Institute of Ophthalmology, underscoring the collaborative and well-funded nature of this pivotal scientific endeavor. The PRIMA system represents a beacon of hope, transforming the lives of those with previously untreatable blindness and paving the way for future advancements in vision restoration.