The transformative potential of this technology is further underscored by the fact that, with the assistance of advanced digital features integrated into the smart glasses, such as adjustable zoom and enhanced contrast settings, some participants achieved visual sharpness levels that rivaled 20/42 vision. These groundbreaking findings, meticulously detailed and validated, were officially published on October 20th in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, a testament to the study’s scientific rigor and its profound implications for ophthalmology.

A Milestone Achieved: Restoring Functional Vision Beyond Light Perception

The implant, a marvel of bioengineering christened PRIMA and developed with dedication at Stanford Medicine, stands as the very first prosthetic eye device capable of restoring usable vision to individuals whose sight loss was previously considered untreatable. This remarkable technology empowers patients to discern shapes and recognize patterns, achieving a level of vision known as "form vision," a significant advancement beyond mere light sensitivity.

Daniel Palanker, PhD, a distinguished professor of ophthalmology and a co-senior author of the pivotal paper, articulated the magnitude of this achievement: "All previous attempts to provide vision with prosthetic devices resulted in basically light sensitivity, not really form vision. We are the first to provide form vision." This statement encapsulates the paradigm shift that PRIMA represents in the field of visual prosthetics.

The research initiative was a collaborative endeavor, co-led by José-Alain Sahel, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Frank Holz, MD, from the University of Bonn in Germany, served as the lead author, coordinating the extensive efforts of a global team.

Unveiling the Ingenious Mechanics of the PRIMA System

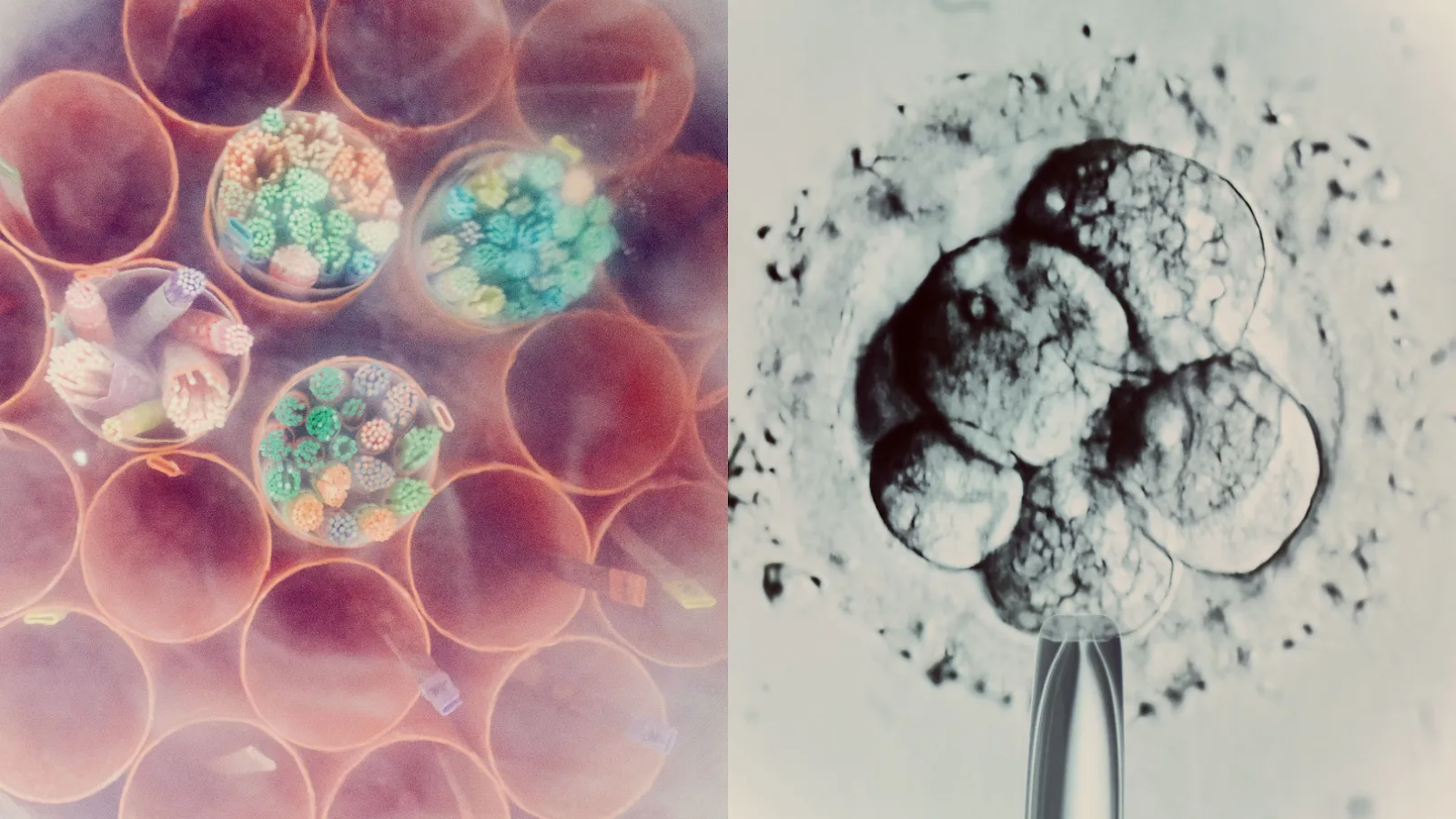

The PRIMA system is elegantly designed, comprising two principal components: a miniaturized camera, seamlessly integrated into a pair of advanced smart glasses, and a wireless chip that is surgically implanted within the retina. The camera functions as an external eye, capturing visual information from the environment. This captured data is then transmitted as an infrared light projection to the implanted chip. Upon receiving this projection, the chip skillfully converts the infrared signals into electrical impulses. These generated electrical signals effectively act as a surrogate for the damaged photoreceptor cells – the light-sensing cells in the eye that are responsible for detecting light and relaying visual information to the brain. In essence, PRIMA bypasses the defunct photoreceptors and directly stimulates the remaining retinal neurons, allowing the brain to interpret these signals as vision.

The development of the PRIMA project is the culmination of nearly two decades of relentless scientific pursuit, a journey marked by numerous iterative prototypes, extensive animal testing to refine its safety and efficacy, and an initial human trial that paved the way for this latest, highly successful clinical study.

Professor Palanker first conceived of this audacious idea twenty years ago, during his work with ophthalmic lasers aimed at treating various eye disorders. His realization was profound: "I realized we should use the fact that the eye is transparent and deliver information by light." This foundational insight, coupled with years of dedicated research and development, has brought his initial vision to fruition. As he aptly put it, "The device we imagined in 2005 now works in patients remarkably well."

Replacing Lost Photoreceptors: A Targeted Approach to Blindness

The participants in this latest, pivotal trial were individuals suffering from an advanced stage of age-related macular degeneration, specifically a condition known as geographic atrophy. This debilitating condition progressively destroys central vision, impacting the ability to see fine details. Globally, geographic atrophy affects over 5 million people and stands as the leading cause of irreversible blindness among older adults.

In the context of macular degeneration, the crucial light-sensitive photoreceptor cells located in the central retina deteriorate and die off, leaving individuals with only limited peripheral vision. However, a critical observation by researchers is that many of the retinal neurons responsible for processing visual information often remain intact, even when the photoreceptors are lost. The PRIMA system ingeniously capitalizes on these surviving neural structures, providing a pathway for vision restoration.

The implant itself is remarkably small, measuring just 2 by 2 millimeters. It is carefully positioned in the specific area of the retina where the photoreceptors have been irreversibly lost. A key distinction of the PRIMA chip is its operational mechanism: unlike natural photoreceptors that respond to visible light, the chip is designed to detect infrared light, which is emitted by the smart glasses.

"The projection is done by infrared because we want to make sure it’s invisible to the remaining photoreceptors outside the implant," explained Palanker. This strategic use of infrared light ensures that the prosthetic vision does not interfere with any residual natural vision that patients may still possess in their peripheral field.

The Synergy of Natural and Artificial Vision: A Holistic Approach

This sophisticated design offers a significant advantage: it enables patients to utilize both their natural peripheral vision and the newly restored prosthetic central vision simultaneously. This dual-vision capability greatly enhances their ability to orient themselves within their environment and navigate their surroundings with greater confidence and independence.

"The fact that they see simultaneously prosthetic and peripheral vision is important because they can merge and use vision to its fullest," Palanker emphasized. This integration of artificial and natural vision is a crucial aspect of achieving truly functional vision.

Furthermore, the PRIMA implant boasts a significant technological advantage: it is photovoltaic. This means it relies solely on light to generate its own electrical current, eliminating the need for external power sources, batteries, or cumbersome cables that would have to extend outside the eye. This wireless, self-powered operation ensures the safety and biocompatibility of the device when placed beneath the retina, a marked improvement over earlier generations of artificial eye devices that often required more invasive power delivery systems.

Rediscovering the Joy of Reading: A Profound Impact on Daily Life

The new clinical trial, which yielded such promising results, enrolled 38 participants, all of whom were over 60 years of age and had been diagnosed with geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration. Critically, these individuals had a visual acuity of worse than 20/320 in at least one eye, meaning they had severely impaired vision.

Following the implantation of the chip in one eye, patients began using the smart glasses four to five weeks later. While some individuals were able to discern basic patterns almost immediately, all participants showed significant improvements in their visual acuity over several months of dedicated training.

"It may take several months of training to reach top performance — which is similar to what cochlear implants require to master prosthetic hearing," Palanker noted, drawing a parallel to the rehabilitation process for other sensory prosthetics.

Of the 32 participants who successfully completed the one-year trial, a remarkable 27 were able to read, and 26 demonstrated a clinically meaningful improvement in their visual acuity. This improvement was defined as the ability to read at least two additional lines on a standard eye chart. On average, participants experienced an enhancement of their visual acuity by five lines, with one individual showing an astonishing improvement of twelve lines.

The practical impact of this restored vision on the participants’ daily lives cannot be overstated. They were able to use the prosthesis to engage in activities they had long been deprived of, such as reading books, deciphering food labels, and navigating public transportation by reading subway signs. The smart glasses provided them with fine-tuned control over contrast and brightness, and the ability to magnify objects up to twelve times, further enhancing their visual capabilities. The user satisfaction survey revealed that two-thirds of the participants reported medium to high levels of satisfaction with the device.

It is important to acknowledge that, as with any medical procedure, there were some side effects. Nineteen participants experienced adverse events, including ocular hypertension (an increase in pressure within the eye), tears in the peripheral retina, and subretinal hemorrhage (bleeding beneath the retina). However, none of these side effects were life-threatening, and almost all of them resolved within a two-month period, highlighting the generally safe profile of the implant.

Gazing Towards the Future: Enhancing Resolution and Expanding Applications

While the current PRIMA device offers black-and-white vision without intermediate shades, Professor Palanker is actively developing advanced software that will soon introduce the full range of grayscale, significantly enhancing the richness and detail of the restored vision.

"Number one on the patients’ wish list is reading, but number two, very close behind, is face recognition," he stated. "And face recognition requires grayscale." The ability to recognize faces is a deeply human need, and achieving this would represent another profound milestone for individuals with vision loss.

Furthermore, Palanker and his team are actively engineering new chips designed to deliver higher resolution vision. The current resolution is limited by the size of the pixels on the chip, which are approximately 100 microns wide, with a total of 378 pixels on each chip. The next generation of chips, which have already undergone successful testing in rats, are being developed with pixels as small as 20 microns wide, promising to accommodate an astonishing 10,000 pixels on each chip. This dramatic increase in pixel density will lead to a significant improvement in visual clarity and detail.

Beyond age-related macular degeneration, Palanker also expresses a strong desire to test the PRIMA device for other types of blindness caused by the loss of photoreceptor cells, broadening the potential impact of this revolutionary technology.

"This is the first version of the chip, and resolution is relatively low," Palanker acknowledged. "The next generation of the chip, with smaller pixels, will have better resolution and be paired with sleeker-looking glasses."

He projects that a chip with 20-micron pixels could potentially provide a patient with 20/80 vision. However, he optimistically adds, "But with electronic zoom, they could get close to 20/20." This suggests that with further technological advancements and the sophisticated capabilities of the smart glasses, vision approaching that of healthy, unimpaired sight may become a tangible reality for many.

The groundbreaking study benefited from the contributions of a vast network of researchers from institutions worldwide, including the University of Bonn, Germany; Hôpital Fondation A. de Rothschild, France; Moorfields Eye Hospital and University College London; Ludwigshafen Academic Teaching Hospital; University of Rome Tor Vergata; Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, University of Lübeck; L’Hôpital Universitaire de la Croix-Rousse and Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1; Azienda Ospedaliera San Giovanni Addolorata; Centre Monticelli Paradis and L’Université d’Aix-Marseille; Intercommunal Hospital of Créteil and Henri Mondor Hospital; Knappschaft Hospital Saar; Nantes University; University Eye Hospital Tübingen; University of Münster Medical Center; Bordeaux University Hospital; Hôpital National des 15-20; Erasmus University Medical Center; University of Ulm; Science Corp.; University of California, San Francisco; University of Washington; University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; and Sorbonne Université.

The crucial research was generously supported by funding from Science Corp., the National Institute for Health and Care Research, Moorfields Eye Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust, and University College London Institute of Ophthalmology, underscoring the collaborative and well-supported nature of this transformative scientific endeavor.