The core of this breakthrough lies in strontium titanate’s unique electro-optic and piezoelectric characteristics, which become exceptionally pronounced at low temperatures. As explained by Jelena Vuckovic, professor of electrical engineering at Stanford and senior author of the study, "Strontium titanate has electro-optic effects 40 times stronger than the most-used electro-optic material today. But it also works at cryogenic temperatures, which is beneficial for building quantum transducers and switches that are current bottlenecks in quantum technologies." This means STO can manipulate light with unprecedented efficacy and efficiency in the extreme cold required for many quantum applications.

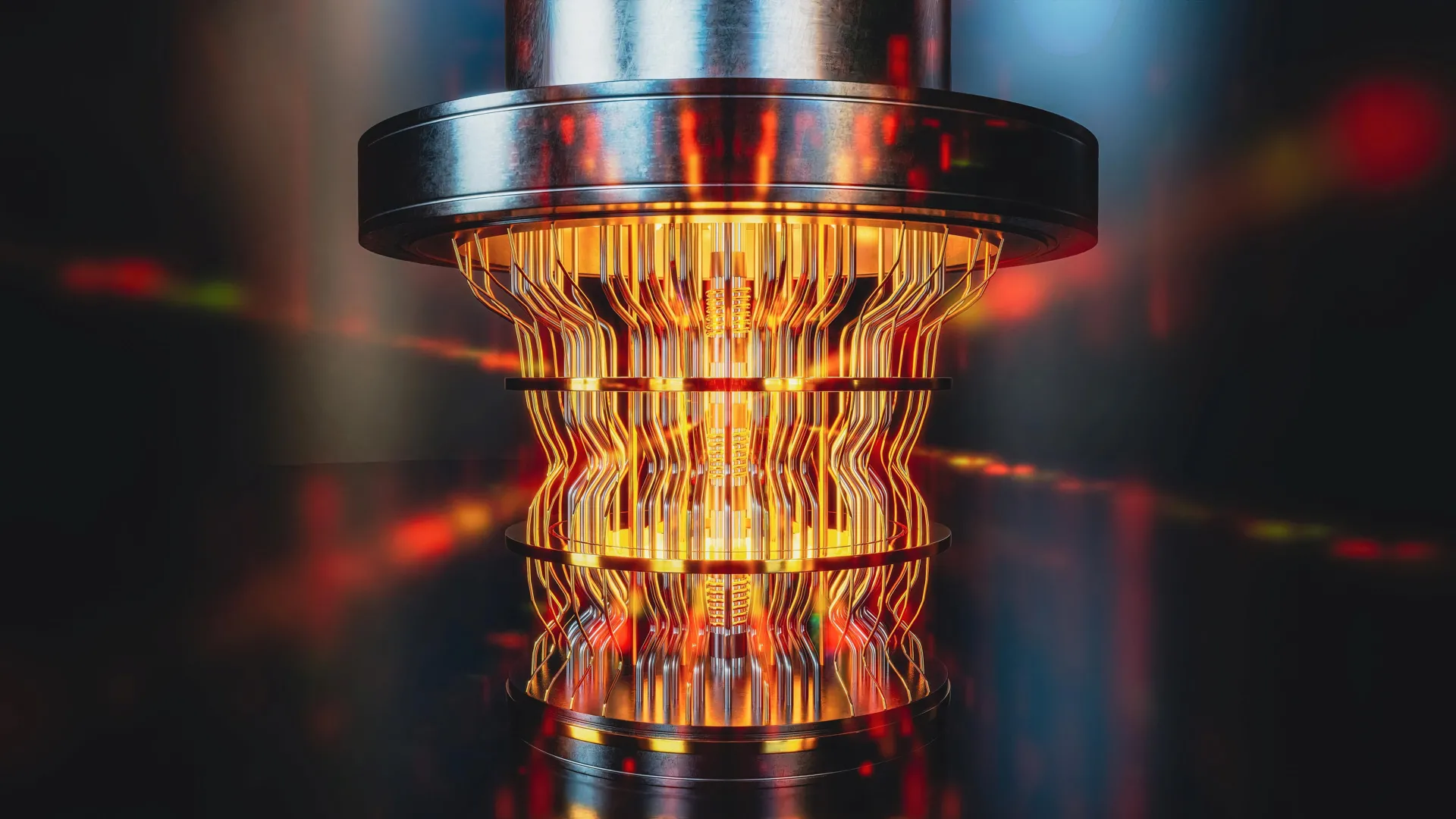

The "non-linear" optical behavior of STO is key to its transformative potential. This property signifies that its optical and mechanical characteristics can be dramatically altered by the application of an electric field. This tunability allows scientists to precisely control the frequency, intensity, phase, and direction of light, functionalities that are crucial for developing novel optical devices capable of operating in extreme environments. Imagine light-based switches for quantum computers that are not only incredibly fast but also operate flawlessly at near absolute zero, a feat previously considered challenging for many materials. This level of control is essential for building the complex infrastructure required for robust quantum computation, where even minute fluctuations can disrupt delicate quantum states.

Furthermore, STO’s piezoelectric nature, its ability to physically deform in response to electric fields, makes it an ideal candidate for developing advanced electromechanical components. These components are vital for various applications, including precise actuators and sensors that must function reliably in the vacuum of space or within the cryogenic fuel systems of rockets. Christopher Anderson, a co-first author of the study and now a faculty member at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, elaborated on this point: "At low temperature, not only is strontium titanate the most electrically tunable optical material we know of, but it’s also the most piezoelectrically tunable material." This dual capability of exceptional optical and mechanical tunability in extreme cold positions STO as a versatile material for a wide array of future technologies.

What makes this discovery even more remarkable is that strontium titanate is not a newly synthesized material. It has been known and studied for decades, readily available, and relatively inexpensive. Giovanni Scuri, a postdoctoral scholar in Vuckovic’s lab and a co-first author, highlighted this accessible nature: "STO is not particularly special. It’s not rare. It’s not expensive. In fact, it has often been used as a diamond substitute in jewelry or as a substrate for growing other, more valuable materials. Despite being a ‘textbook’ material, it performs exceptionally well in a cryogenic context." This accessibility means that the transition from laboratory discovery to real-world implementation could be significantly faster and more cost-effective than with exotic or newly developed materials. The researchers’ approach was to understand the fundamental principles of what makes a material highly tunable and then to identify existing materials that possessed these qualities. Anderson explained their strategic selection: "We knew what ingredients we needed to make a highly tunable material. We found those ingredients already existed in nature, and we simply used them in a new recipe. STO was the obvious choice. When we tried it, surprisingly, it matched our expectations perfectly." This intelligent application of existing knowledge to a readily available material underscores the elegance of the discovery. Scuri further added that the framework developed by the team could serve as a blueprint for identifying or improving other nonlinear materials for diverse operating conditions.

The performance of STO at cryogenic temperatures was nothing short of astonishing. Tested at a mere 5 Kelvin (-450°F), its nonlinear optical response was found to be an astounding 20 times greater than that of lithium niobate, the current industry standard for nonlinear optical materials. It also outperformed barium titanate, previously considered the benchmark for cryogenic applications, by nearly a factor of three. This dramatic improvement in performance at extremely low temperatures is a game-changer for quantum technology.

The researchers didn’t stop there; they further pushed the boundaries of STO’s capabilities by employing a clever isotopic substitution. By replacing a portion of the oxygen atoms in the crystal with heavier isotopes, specifically by adding just two neutrons to exactly 33 percent of the oxygen atoms, they were able to move STO closer to a state known as quantum criticality. This delicate manipulation resulted in an even more significant increase in tunability, boosting it by an astonishing factor of four. "We precisely tuned our recipe to get the best possible performance," Anderson stated, emphasizing the meticulous nature of their optimization process. This ability to fine-tune material properties through isotopic engineering opens up new avenues for developing highly specialized materials for specific quantum applications.

Beyond its exceptional performance, STO offers practical advantages that make it highly attractive to engineers for the development of next-generation cryogenic devices. It can be synthesized and modified structurally using existing semiconductor fabrication equipment, allowing for large-scale production at the wafer level. This compatibility with established manufacturing processes significantly lowers the barrier to entry for incorporating STO into complex quantum devices, such as the laser-based switches essential for controlling and transmitting quantum information.

The significance of this research has not gone unnoticed by industry leaders. Funding for this pioneering work was partially provided by tech giants such as Samsung Electronics and Google’s quantum computing division, both actively seeking materials to advance their quantum hardware. The Stanford team’s next objective is to leverage STO’s unique properties to design and build fully functional cryogenic devices. Anderson aptly summarized the journey: "We found this material on the shelf. We used it and it was amazing. We understood why it was good. Then the cherry on the top — we knew how to do better, added that special sauce, and we made the world’s best material for these applications. It’s a great story." This narrative of rediscovering and enhancing an overlooked material highlights the power of fundamental research combined with innovative engineering.

The study received additional support from a Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship through the U.S. Department of Defense and the Department of Energy’s Q-NEXT program, underscoring the broad national interest in advancing quantum technologies. The collaborative effort involved researchers from multiple institutions, including Aaron Chan and Lu Li from the University of Michigan, and Sungjun Eun, Alexander D. White, Geun Ho Ahn, Amir Safavi-Naeini, and Kasper Van Gasse from Stanford’s E. L. Ginzton Laboratory, as well as Christine Jilly from the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities. This multidisciplinary approach was instrumental in achieving such a significant breakthrough. The discovery of strontium titanate’s extraordinary cryogenic capabilities represents a pivotal moment in the pursuit of advanced technologies, promising to accelerate the development of powerful quantum computers, enable more ambitious space missions, and unlock entirely new possibilities in fields demanding extreme cold performance.