However, as the global race to develop the first robust and commercially viable large-scale quantum computer intensifies, a fundamental and increasingly pressing issue has emerged: how can we definitively confirm the correctness of the answers produced by these revolutionary devices, especially when they are designed to solve problems deemed computationally intractable for classical machines? This critical question has spurred significant research efforts, and a recent landmark study emanating from Swinburne University offers a promising solution, presenting novel techniques to address this very dilemma.

The inherent difficulty in verifying quantum computations stems from their very nature. As articulated by lead author Alexander Dellios, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Swinburne’s Centre for Quantum Science and Technology Theory, "There exists a range of problems that even the world’s fastest supercomputer cannot solve, unless one is willing to wait millions, or even billions, of years for an answer." This temporal barrier makes direct comparison with classical computation an impractical, if not impossible, method for validation. Consequently, for quantum computers to gain widespread trust and adoption, innovative approaches are imperative to compare theoretical predictions with experimental results without succumbing to prohibitive waiting times.

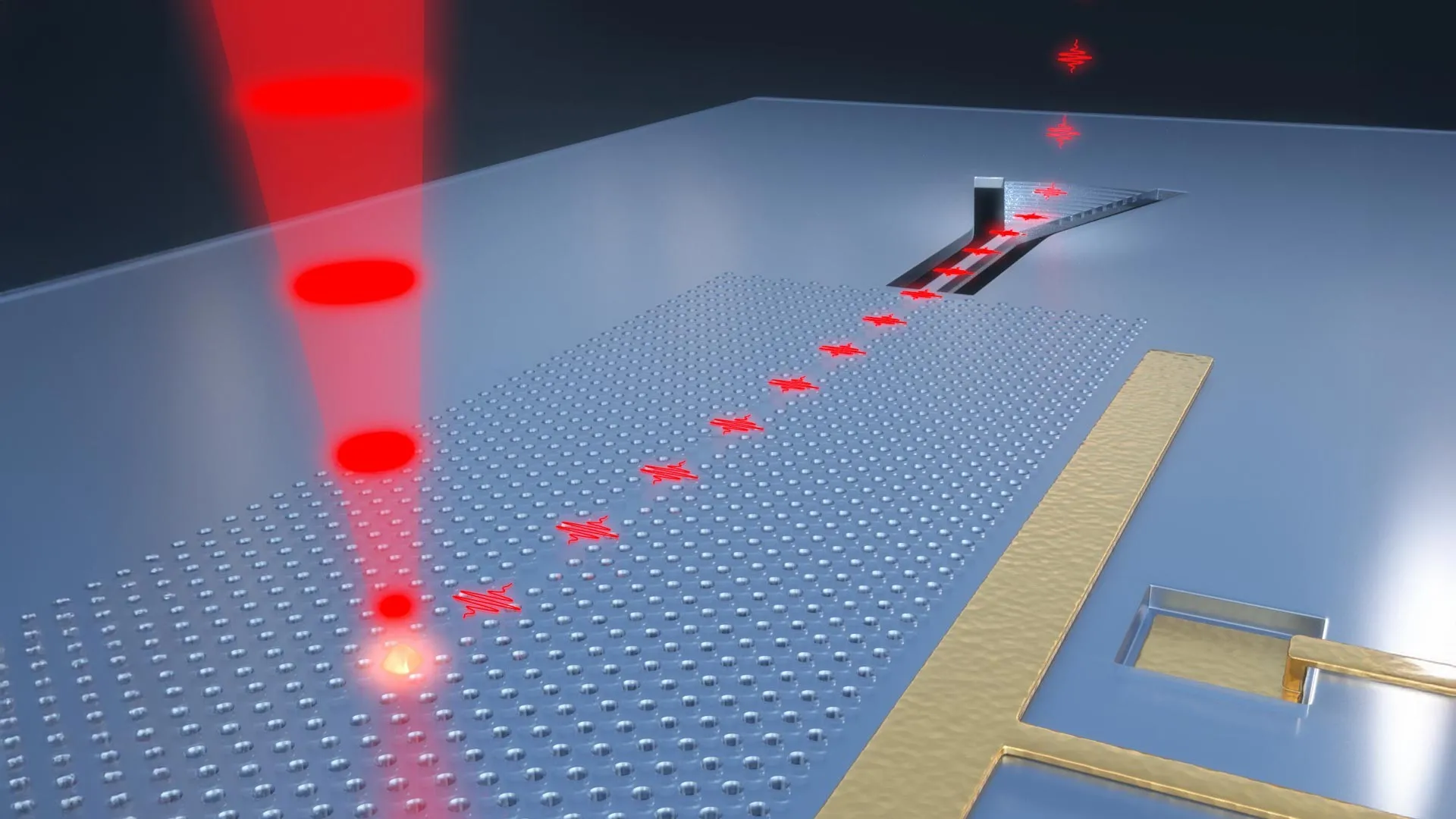

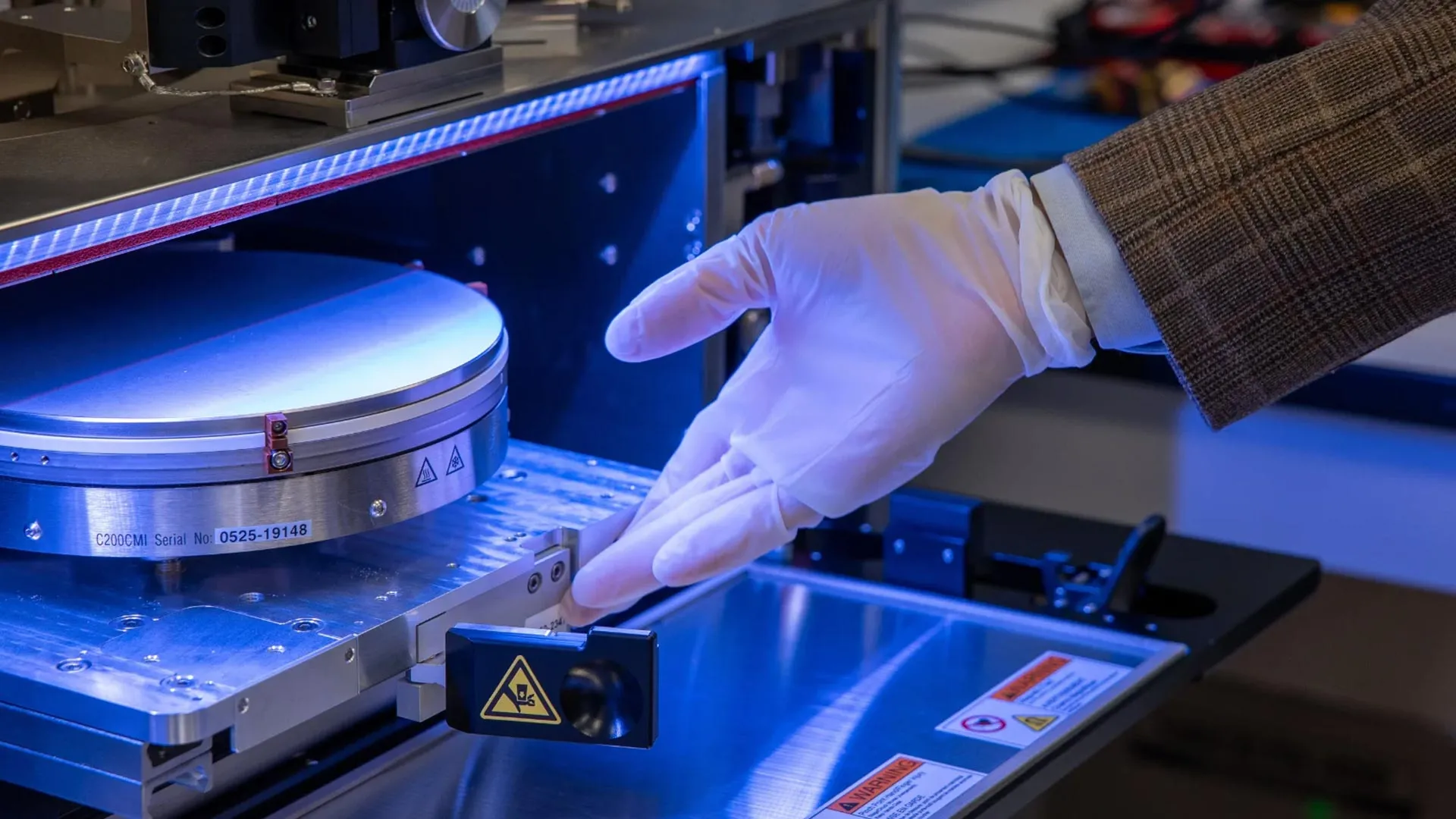

The research team at Swinburne University has risen to this challenge by developing ingenious new techniques specifically designed to confirm the accuracy of a particular class of quantum devices known as Gaussian Boson Samplers (GBS). These GBS machines operate by harnessing photons, the fundamental particles of light, to perform complex probability calculations. The sheer scale of these calculations is staggering; for a classical supercomputer, even the most advanced available today, to replicate the probability distributions generated by a GBS machine would necessitate thousands of years of continuous operation. This highlights the profound computational advantage offered by quantum systems, but simultaneously underscores the validation conundrum.

The newly developed techniques offer a remarkably efficient solution to this validation problem. Dellios elaborates on their significance: "In just a few minutes on a laptop, the methods developed allow us to determine whether a GBS experiment is outputting the correct answer and what errors, if any, are present." This dramatic reduction in verification time, from millennia to mere minutes, represents a monumental leap forward. It democratizes the validation process, making it accessible to a much wider range of researchers and developers, and crucially, enabling rapid iteration and improvement of quantum hardware.

To rigorously test and demonstrate the efficacy of their novel approach, the Swinburne researchers applied it to a recently published GBS experiment. This particular experiment, according to their analysis, would have required a minimum of 9,000 years for current supercomputers to reproduce. The results of their verification were eye-opening. The analysis revealed a significant discrepancy: the probability distribution produced by the GBS experiment did not align with the intended target, suggesting an issue with the computation itself. Furthermore, their techniques uncovered additional sources of "noise" within the experiment that had not been identified or accounted for in the original publication. This ability to pinpoint previously unknown errors is a testament to the sensitivity and power of the new validation tools.

The discovery of this unexpected distribution and the presence of uncharacterized noise raises further questions that are central to the advancement of quantum computing. The next critical step for the researchers is to determine whether the reproduction of this anomalous distribution is itself a computationally demanding task, or whether the observed errors are a consequence of the device losing its crucial "quantumness." This distinction is vital, as it helps differentiate between errors that can be corrected through algorithmic adjustments and those that point to fundamental limitations or malfunctions in the quantum hardware itself. Understanding and mitigating these errors is paramount to achieving reliable quantum computation.

The implications of this groundbreaking investigation extend far beyond the specific domain of GBS machines. The outcome of this research has the potential to profoundly shape the trajectory of development for large-scale, error-free quantum computers that are suitable for widespread commercial application. This is a goal that Dellios ardently hopes to contribute to leading. He emphasizes the immense undertaking involved in realizing this vision: "Developing large-scale, error-free quantum computers is a herculean task that, if achieved, will revolutionize fields such as drug development, AI, cyber security, and allow us to deepen our understanding of the physical universe."

The newly developed validation methods are not merely an academic curiosity; they represent a vital component in the arduous journey towards fault-tolerant quantum computing. By providing scalable and efficient ways to verify quantum computations, these techniques will significantly enhance our understanding of the types of errors that plague quantum systems and, more importantly, offer pathways to correct them. This meticulous process of error identification and correction is essential to ensuring that quantum computers retain their extraordinary "quantumness" – the unique quantum mechanical properties that grant them their computational power.

The ability to reliably verify quantum computations is an indispensable prerequisite for building trust in these nascent technologies. Without robust validation mechanisms, the revolutionary potential of quantum computers will remain largely theoretical, hampered by skepticism and the inability to confirm their outputs. The work by Dellios and his team at Swinburne University marks a significant stride towards overcoming this hurdle, providing a tangible and practical solution that will accelerate the development of quantum computers capable of ushering in a new era of scientific discovery and technological innovation. This breakthrough not only addresses the immediate need for validation but also lays a crucial foundation for the future of quantum computing, promising to unlock its full transformative potential across a vast spectrum of human endeavor. The ability to confidently state that a quantum computer’s answer is correct is as important as the ability to arrive at that answer in the first place, and this research has provided a critical piece of that puzzle.