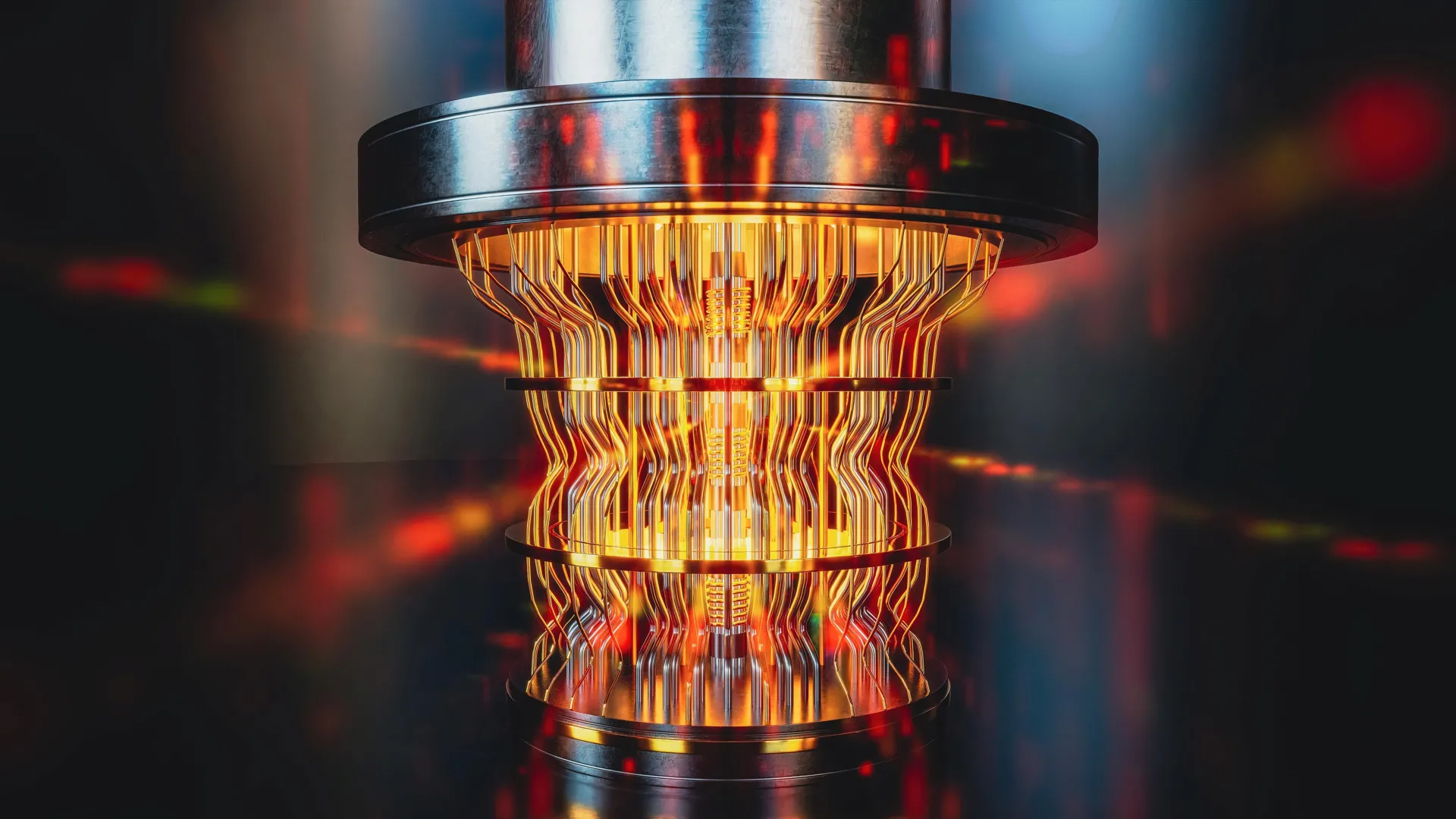

Quantum computing, a paradigm shift from the binary logic of classical computers, promises to tackle problems of immense complexity that are currently intractable. These machines harness the bizarre principles of quantum mechanics, such as superposition and entanglement, to perform calculations at speeds and scales unimaginable for even the most powerful supercomputers. The potential applications are vast and transformative. In physics, quantum computers could unlock deeper insights into the fundamental nature of the universe, simulating quantum systems with unparalleled fidelity. Medical research stands to benefit immensely, with the possibility of designing new drugs and personalized treatments by accurately modeling molecular interactions. Cryptography is another area ripe for revolution, as quantum computers could break existing encryption methods, necessitating the development of quantum-resistant security protocols.

However, as the race to build the first reliable, large-scale commercial quantum computer intensifies, a fundamental question looms large: how can we be certain that the answers these machines provide are correct? When a quantum computer tackles a problem that would take a classical supercomputer millions, or even billions, of years to solve, there is no practical way to cross-reference the result. This lack of verification has been a significant bottleneck, casting a shadow of doubt over the reliability of early quantum devices and slowing down their widespread adoption.

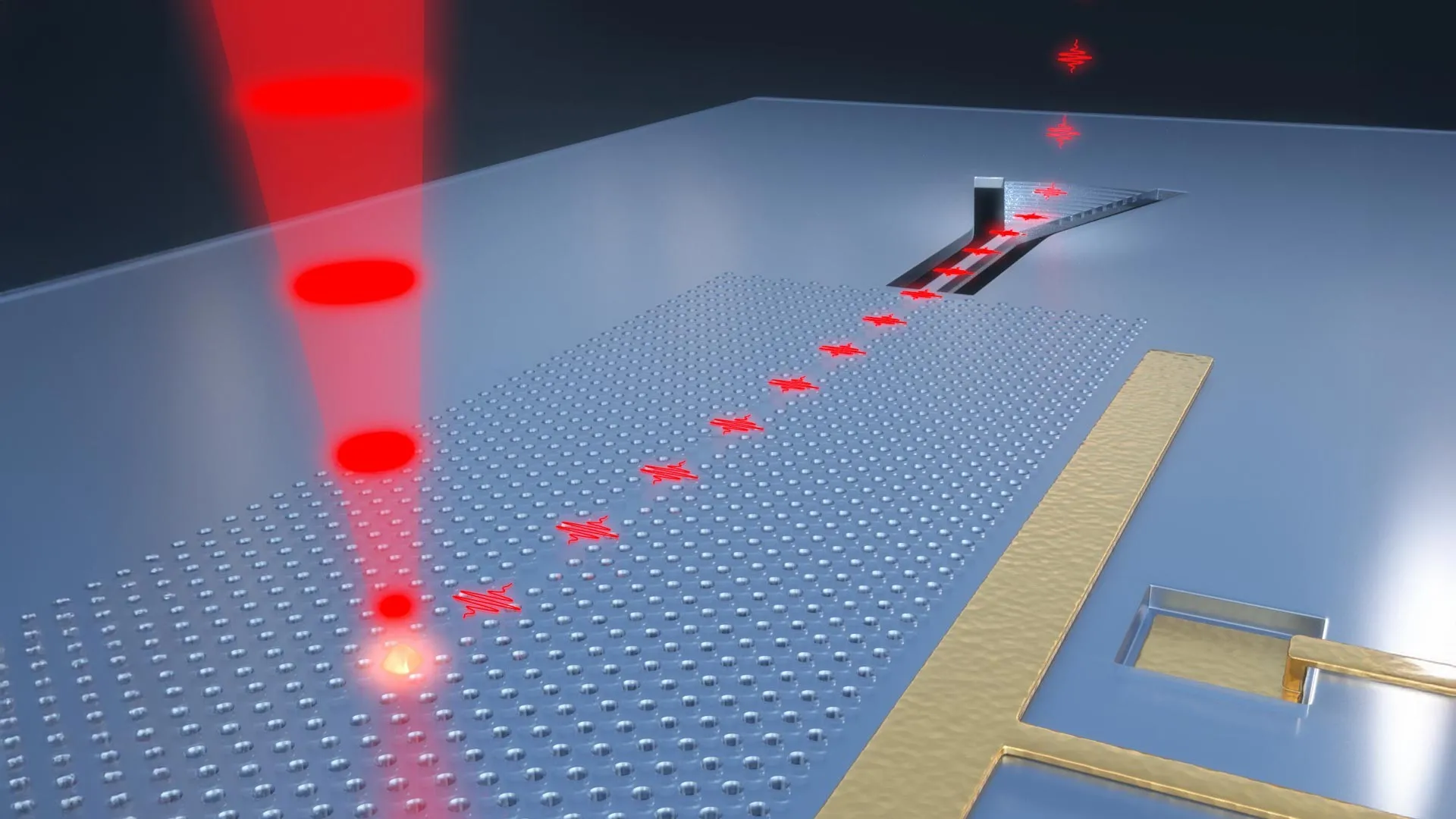

It is within this critical context that the recent study from Swinburne University emerges as a beacon of progress. Led by Alexander Dellios, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Swinburne’s Centre for Quantum Science and Technology Theory, the research team has developed novel techniques to address this dilemma head-on. Their work focuses on a specific type of quantum device known as a Gaussian Boson Sampler (GBS). GBS machines operate by manipulating photons, the fundamental particles of light, to generate complex probability distributions. These calculations are so computationally intensive that even the fastest classical supercomputers would require millennia to replicate them.

Dellios explains the core of the problem: "There exists a range of problems that even the world’s fastest supercomputer cannot solve, unless one is willing to wait millions, or even billions, of years for an answer. Therefore, in order to validate quantum computers, methods are needed to compare theory and result without waiting years for a supercomputer to perform the same task." This highlights the urgent need for efficient and scalable verification techniques that can keep pace with the rapid advancements in quantum hardware.

The Swinburne team’s innovative approach offers precisely this solution. They have devised new methods that can confirm the accuracy of a GBS experiment in a remarkably short timeframe – "in just a few minutes on a laptop," according to the researchers. These techniques not only determine whether the GBS experiment is outputting the correct answer but also identify any errors that may be present and quantify their impact. This is a monumental leap forward, transforming the process of quantum computer verification from an insurmountable challenge into a manageable and routine task.

To demonstrate the power of their new tools, the researchers applied them to a recently published GBS experiment. The original experiment’s results were so complex that reproducing them with current supercomputers was estimated to take at least 9,000 years. The analysis conducted by Dellios and his team revealed a critical discrepancy: the probability distribution generated by the experiment did not align with the intended target. Furthermore, their methods uncovered previously undetected noise within the experiment, suggesting that the device was not performing as expected.

This finding has significant implications. The next crucial step for the researchers is to determine whether the unexpected distribution observed is inherently computationally difficult to reproduce, a characteristic that would actually be a sign of genuine quantum advantage. Alternatively, the observed errors could indicate that the device has lost its crucial "quantumness," meaning it is no longer exhibiting quantum mechanical behavior. Distinguishing between these possibilities is essential for understanding the limitations and capabilities of current GBS devices.

The broader impact of this investigation extends far beyond the realm of GBS. The principles and techniques developed by the Swinburne team have the potential to be generalized and applied to other types of quantum computing architectures. This could pave the way for the development of large-scale, error-free quantum computers that are suitable for commercial use – a long-held aspiration in the field. Dellios expresses his hope to be at the forefront of this endeavor, stating, "Developing large-scale, error-free quantum computers is a herculean task that, if achieved, will revolutionize fields such as drug development, AI, cyber security, and allow us to deepen our understanding of the physical universe."

The ability to reliably verify quantum computations is not merely an academic exercise; it is a fundamental requirement for building trust and confidence in these powerful new machines. As Dellios emphasizes, "A vital component of this task is scalable methods of validating quantum computers, which increase our understanding of what errors are affecting these systems and how to correct for them, ensuring they retain their ‘quantumness’." By providing clear insights into the sources and nature of errors, this research will guide the development of more robust quantum hardware and sophisticated error correction strategies.

The implications of this breakthrough are far-reaching. Imagine a future where quantum computers can accurately simulate complex biological molecules, leading to the rapid discovery of life-saving drugs for diseases that currently have no cure. Envision artificial intelligence systems that can learn and solve problems with a level of insight and efficiency previously unimaginable, transforming everything from scientific research to everyday life. Consider the enhanced security of our digital world, with quantum-resistant cryptography protecting our sensitive data from the prying eyes of future adversaries. These are just a few of the transformative possibilities that hinge on the development of reliable and verifiable quantum computers.

This new verification method acts as a crucial diagnostic tool, allowing researchers to peek under the hood of quantum computations and identify precisely where things might be going wrong. It’s akin to having a highly sophisticated multimeter for the quantum realm. By quickly pinpointing deviations from expected behavior, scientists can then focus their efforts on understanding the root causes of these errors, whether they stem from imperfections in the quantum hardware, environmental noise, or limitations in the algorithms themselves. This targeted approach to error correction is paramount for building fault-tolerant quantum computers, which are essential for performing long and complex calculations reliably.

The scientific community is abuzz with excitement over this development. Many researchers have long recognized the "verification problem" as a major hurdle. This new work by Dellios and his team offers a tangible and practical solution, demonstrating that it is indeed possible to assess the validity of quantum computations without resorting to impractical classical simulations. This could accelerate the timeline for achieving quantum supremacy in various domains and bring the era of quantum advantage closer to reality.

Looking ahead, the Swinburne University team plans to explore the applicability of their methods to other quantum computing platforms, such as superconducting qubits and trapped ions. They also aim to further refine their techniques to detect and characterize an even wider range of errors. The ultimate goal is to develop a comprehensive suite of verification tools that can be integrated into the standard workflow of quantum computing research and development.

In conclusion, the discovery of a method to reliably tell if quantum computers are wrong is a pivotal moment in the quest for quantum computing’s full realization. This breakthrough from Swinburne University not only addresses a critical technical challenge but also fuels optimism for a future where quantum computers will drive unprecedented progress across a multitude of scientific and technological frontiers. The ability to verify quantum results is the bedrock upon which the future of this transformative technology will be built.