A perplexing, spire-shaped organism that dominated terrestrial landscapes over 400 million years ago, known as Prototaxites, is now challenging the fundamental classification of life on Earth, with a groundbreaking study published in Science Advances arguing it represents an entirely new biological kingdom hitherto unknown to science. For over a century, Prototaxites has baffled paleontologists, oscillating between classifications as an extinct tree, a giant alga, and most recently, an enormous fungus, but new analyses of its intricate internal structures reveal features so distinct they defy placement within any existing biological grouping. Matthew Nelsen, a senior research scientist at the Field Museum of Natural History, aptly captures the scientific community’s bewilderment, stating, "It feels like it doesn’t fit comfortably anywhere. People have tried to shoehorn it into these different groups, but there are always things that don’t make sense." This revelation compels scientists to reconsider the early evolution of complex life and the very structure of the tree of life itself, proposing a profound reevaluation of how life colonized and transformed Earth’s primordial landmasses.

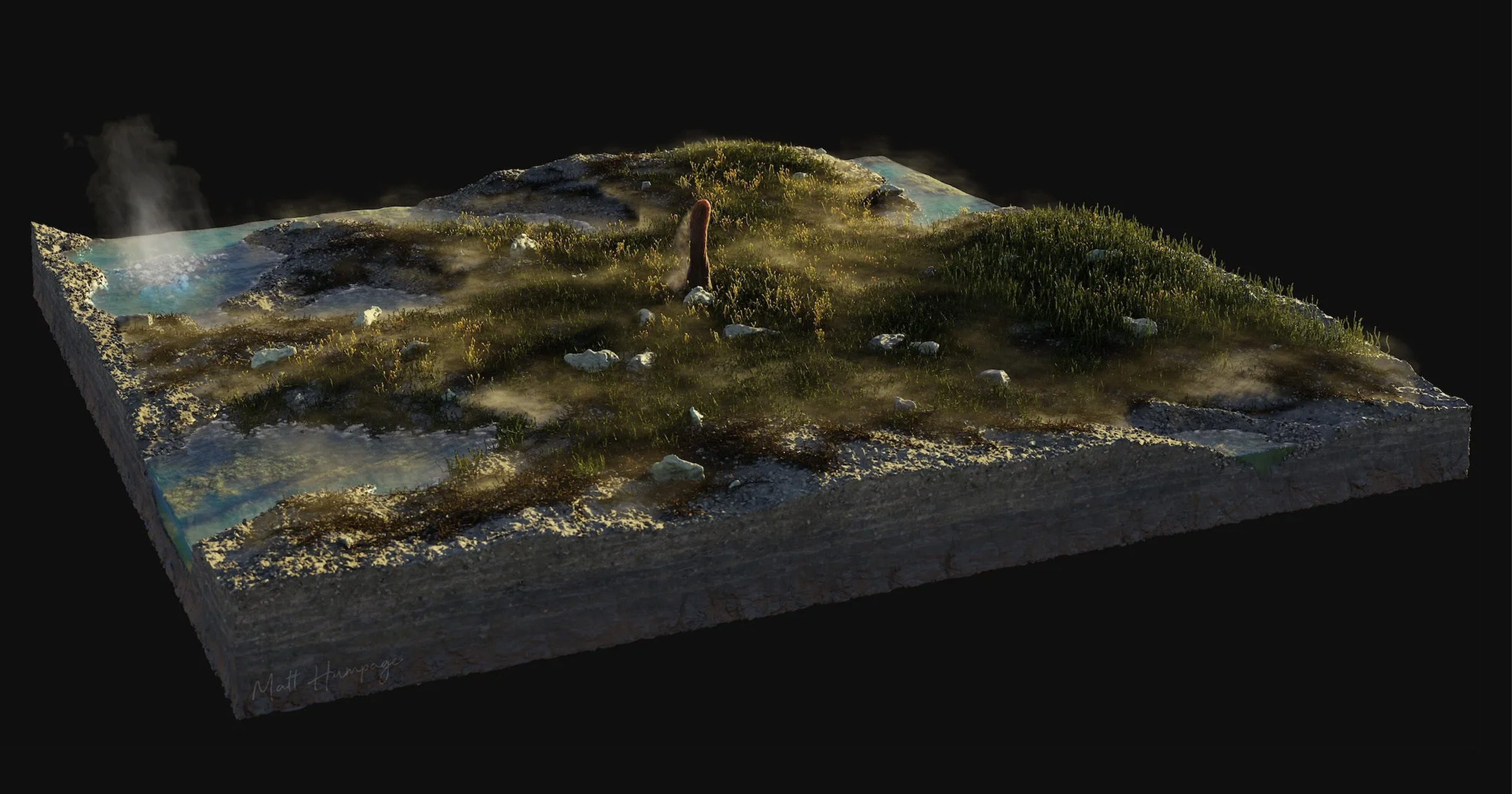

The saga of Prototaxites began in 1855 with the discovery of massive, columnar fossils in Gaspé Bay, Quebec, by Canadian geologist John William Dawson. Resembling petrified tree trunks, the fossils were initially named "Prototaxites," meaning "early yew," reflecting the prevailing assumption that they were the remains of an ancient conifer, an ancestor to modern yew trees. This interpretation held sway for decades, particularly because these "trunks" could reach an astonishing height of up to 26 feet (around 8 meters) and a diameter of 3 feet, making them the tallest organisms on land during the Silurian and early Devonian periods. To put this into perspective, during a time when the tallest terrestrial plants were merely knee-high, these colossal structures would have towered majestically over the nascent land ecosystems, creating the planet’s first "forests" long before true trees with woody stems evolved.

However, as paleontological techniques advanced and understanding of early Earth’s flora expanded, the "early yew" hypothesis began to unravel. The internal anatomy of Prototaxites, with its unique arrangement of tubular structures, bore little resemblance to the vascular tissues found in true trees. By the mid-20th century, the consensus shifted, proposing that Prototaxites was a gigantic form of alga, perhaps a brown alga, adapted to terrestrial or semi-terrestrial environments. This theory, though more plausible given the organism’s non-woody structure, also faced challenges, particularly regarding its sheer size and complex internal organization, which seemed uncharacteristic of known algal forms.

The most compelling hypothesis prior to the current study emerged in the early 2000s, suggesting Prototaxites was a massive fungus. This idea gained significant traction due to analysis of carbon isotopes within the fossils. Fungi, being heterotrophs (organisms that absorb nutrients from external sources), often exhibit distinctive carbon isotope ratios, particularly a depletion of carbon-13, due to their metabolic pathways. Studies found that Prototaxites fossils displayed these tell-tale isotopic signatures, seemingly cementing its place within the fungal kingdom. This interpretation envisioned Prototaxites as an immense, stalk-like fruiting body of a subterranean fungal mycelium, playing a crucial role as a decomposer in early terrestrial ecosystems, recycling nutrients and contributing to the formation of the first true soils.

Yet, the new paper boldly challenges this long-held fungal consensus, spearheaded by co-lead author Laura Cooper, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh. Her team’s meticulous re-examination of Prototaxites’ internal structures, using advanced microscopy and chemical analysis, revealed critical discrepancies. While fungi are characterized by a network of ordered, branching filaments called hyphae, the tubelike structures within Prototaxites were found to be remarkably wild and varied, lacking the consistent morphology seen in modern fungi. Crucially, the researchers detected no traces of chitin, a robust polysaccharide that forms the primary component of cell walls in all known fungi. The absence of chitin is a powerful argument against a fungal classification, as it is a defining characteristic of the entire kingdom. "It doesn’t seem to have any of the characteristic features of the living fungal groups," Cooper explained to Scientific American, highlighting that many aspects of its biology, not just its taxonomy, remain profoundly enigmatic. "How it actually works energetically is still a complete mystery."

The implications of this finding are profound. If Prototaxites is neither plant, animal, alga, nor fungus, it forces science to confront the possibility of a truly unique and extinct lineage of complex life that doesn’t fit into any of the established biological kingdoms (Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista, and Monera/Bacteria/Archaea). The concept of a "kingdom" represents a fundamental division in the classification of life, based on shared evolutionary history and distinct biological characteristics. To propose a new kingdom for an organism that vanished hundreds of millions of years ago is a radical step, underscoring how fundamentally different Prototaxites appears to be.

During the Silurian and Devonian periods, Earth’s landmasses were undergoing a dramatic transformation. Primitive plants were just beginning to establish themselves, creating new niches and altering atmospheric composition. Arthropods were also making their first forays onto land. In this nascent terrestrial environment, Prototaxites would have been a dominant feature, its towering structures potentially influencing microclimates, providing shelter, and playing an essential, albeit still mysterious, ecological role. Was it a photosynthetic organism, despite its un-plant-like features? Was it a saprophyte, like a fungus, but employing entirely different biochemical mechanisms? Or did it engage in some form of symbiosis, perhaps with early microbial communities, to derive its energy? The "energetic mystery" Cooper refers to is central to understanding its place in the ancient world.

Some scientists, like Kevin Boyce, a paleobotanist at Stanford University, acknowledge the challenges but suggest that Prototaxites might represent an entirely extinct lineage within the fungal kingdom, one that independently evolved complex, macroscopic forms. Such an evolutionary trajectory would still be astounding, demonstrating parallel evolution of complexity. However, Cooper remains steadfast in her belief that Prototaxites is too "fundamentally different" to be simply shoehorned into the fungi, even as an extinct branch. Science, by its nature, seeks patterns and classifications, and the existence of such a stark outlier hints at an incomplete picture of ancient biodiversity.

The next steps in unraveling the mystery of Prototaxites involve a broader search for its biological kin. Vivi Vajda, a paleobiologist at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, suggests that researchers should now "find other fossil life forms with similar chemical fingerprints to trace this enigmatic life form through the tree of life." Discovering other organisms with shared, unique characteristics could help establish a new, coherent lineage, potentially forming the basis of a new kingdom. Such discoveries would not only expand our understanding of ancient Earth but also force a re-evaluation of the early diversification of complex life and the diverse evolutionary paths taken during the planet’s formative eras. The towering Prototaxites, once a mere curiosity, has now become a profound challenge to our understanding of life itself, a silent sentinel from a distant past that continues to reshape our view of Earth’s biological heritage.