What do children’s building blocks and quantum computing have in common? The answer is modularity. It is difficult for scientists to build quantum computers monolithically – that is, as a single large unit. Quantum computing relies on the manipulation of millions of information units called qubits, but these qubits are difficult to assemble. The solution? Finding modular ways to construct quantum computers. Like plastic children’s bricks that lock together to create larger, more intricate structures, scientists can build smaller, higher quality modules and string them together to form a comprehensive system.

Recognizing the immense potential of these modular systems, researchers from The Grainger College of Engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have unveiled a groundbreaking, enhanced approach to scalable quantum computing. Their work, detailed in a pivotal publication in Nature Electronics, demonstrates a highly viable and remarkably high-performance modular architecture specifically designed for superconducting quantum processors. This innovative design significantly expands upon previous modular concepts and lays a robust foundation for the future development of quantum computing systems that are not only scalable but also fault-tolerant and dynamically reconfigurable.

The inherent limitations of monolithic superconducting quantum systems have long been a significant bottleneck in the advancement of quantum computing. These systems, built as single, large units, are inherently constrained in terms of their overall size and, crucially, their fidelity – a measure of how accurately quantum operations are performed. Scientists strive to achieve a fidelity as close to 1 as possible, signifying near-perfect execution of quantum logic. In contrast to these size-limited monolithic designs, the adoption of modularity offers a compelling suite of advantages. It unlocks the potential for substantial system scalability, facilitates seamless hardware upgrades, and introduces a crucial tolerance to inherent variability within the quantum components. These benefits collectively make modularity a far more attractive and pragmatic strategy for constructing complex quantum computing networks.

Wolfgang Pfaff, an assistant professor of physics and the senior author of the Nature Electronics paper, eloquently articulated the essence of their achievement. "We’ve created an engineering-friendly way of achieving modularity with superconducting qubits," he stated. "The fundamental question we sought to answer was: Can I build a system that I can bring together, allowing me to manipulate two qubits jointly so as to create entanglement or gate operations between them? And crucially, can we achieve this at a very high quality? Furthermore, can we design it such that we can take it apart and put it back together? Typically, we only discover that something has gone wrong after the entire monolithic system has been assembled. Therefore, we are immensely motivated by the prospect of having the ability to reconfigure the system at a later stage."

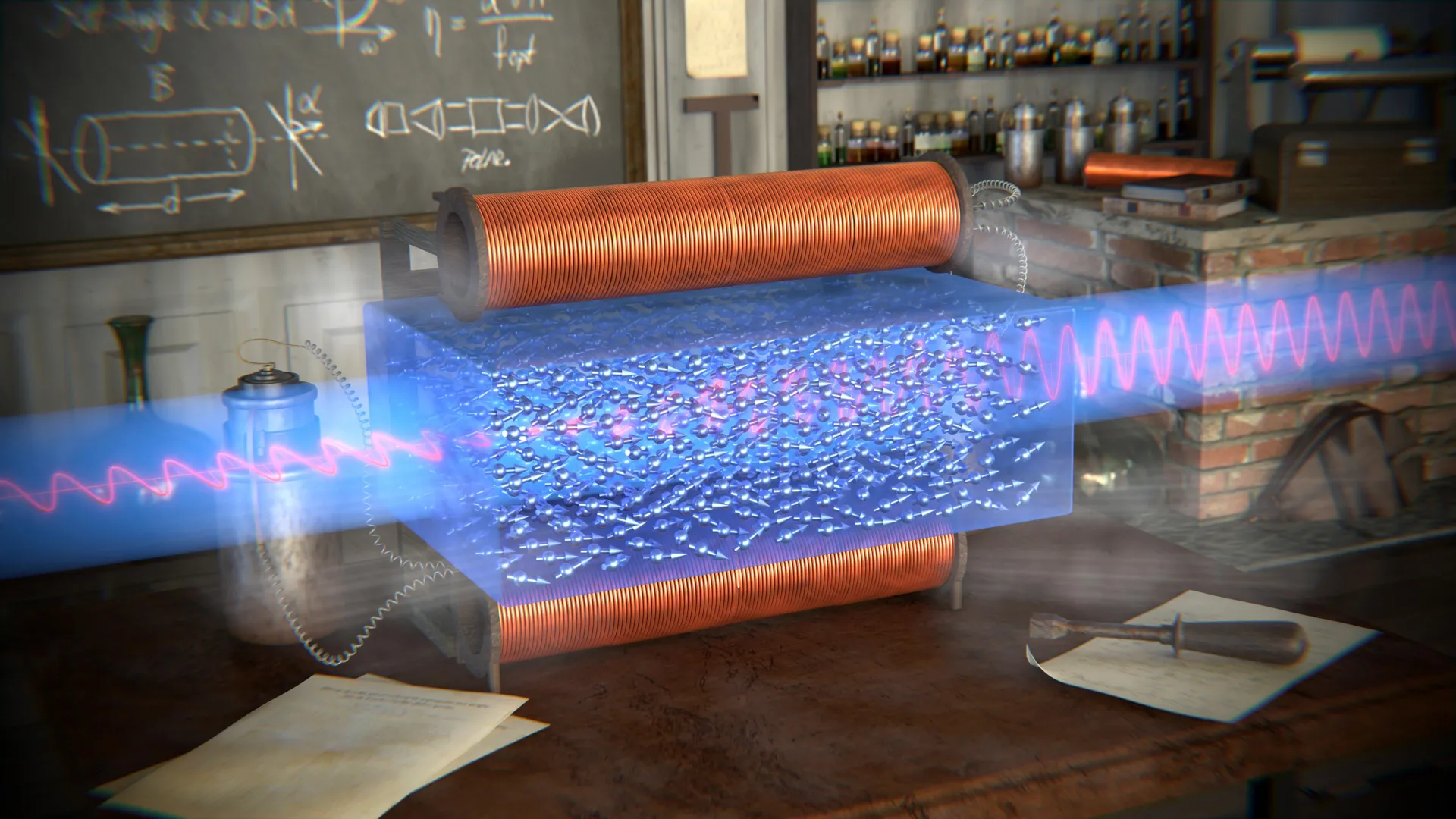

The team’s innovative approach hinges on a clever design where two distinct quantum processing devices are interconnected using specialized superconducting coaxial cables. These cables act as high-speed conduits, effectively linking qubits situated across different modules. Through this elegant modular construction, Pfaff’s team achieved a remarkable SWAP gate fidelity of approximately 99%. This translates to a minuscule loss of less than 1%, signifying an exceptionally high level of precision and reliability in inter-qubit operations. Their demonstrated ability to connect and reconfigure separate quantum modules with a simple cable connection, all while meticulously preserving this high level of operational quality, offers entirely novel and invaluable insights into the critical field of designing robust communication protocols for quantum systems.

"Finding an approach that truly works has been a significant journey for our field," Pfaff reflected. "Many research groups have converged on the understanding that our ultimate goal is the ability to stitch increasingly larger and more complex quantum systems together using cables. Simultaneously, we need to achieve performance metrics that are sufficiently impressive to justify the ambitious undertaking of scaling. The persistent challenge has been identifying the precise combination of engineering tools and quantum design principles that can effectively address these dual demands."

Looking ahead, the dedicated engineers at The Grainger College of Engineering are sharply focused on the next critical phase: scaling their modular architecture. Their immediate objective is to successfully connect more than two quantum processing devices together while meticulously retaining their established ability to efficiently detect and correct errors. This ambitious endeavor will push the boundaries of current quantum interconnectivity and error mitigation strategies.

"We have achieved demonstrably good performance with our current modular design," Pfaff affirmed, emphasizing the solid foundation they have built. "Now, the imperative is to rigorously put this to the test and critically assess whether this modular path truly represents a viable and progressive direction for quantum computing. We need to definitively answer the question: Does it really make sense to pursue this further, and does it hold the key to unlocking the true potential of quantum computation?" The successful realization of this next phase will undoubtedly be a monumental step towards building the powerful and versatile quantum computers of the future.