For decades, the concept of microscopic gears and the engines they power has been a tantalizing prospect. Gears, ubiquitous in everything from the intricate mechanisms of antique clocks to the powerful engines of automobiles and the sophisticated robotics shaping our future, have long been a focus of miniaturization efforts. The dream has been to shrink these essential components to a scale where they could be integrated into microscopic devices, enabling entirely new functionalities. However, progress in this field has been stymied by a seemingly insurmountable barrier: the drive trains themselves. Traditional mechanical linkages and power transmission systems required to make gears move proved exceedingly difficult to miniaturize beyond a certain point, with researchers finding themselves stuck at a limit of approximately 0.1 millimeters. This physical constraint effectively put a ceiling on the size of micro-engines that could be constructed.

The team at the University of Gothenburg, alongside collaborators, has now decisively broken through this long-standing impediment. Their ingenious solution lies in a radical departure from conventional mechanical drive trains. Instead of relying on physical connections, they have harnessed the power of laser light to directly set their microscopic gears in motion. This paradigm shift in thinking has unlocked the potential for unprecedented miniaturization, allowing for the creation of gears and motors that are orders of magnitude smaller than previously achievable.

Gears Powered by Light: A Novel Approach to Micro-Mechanics

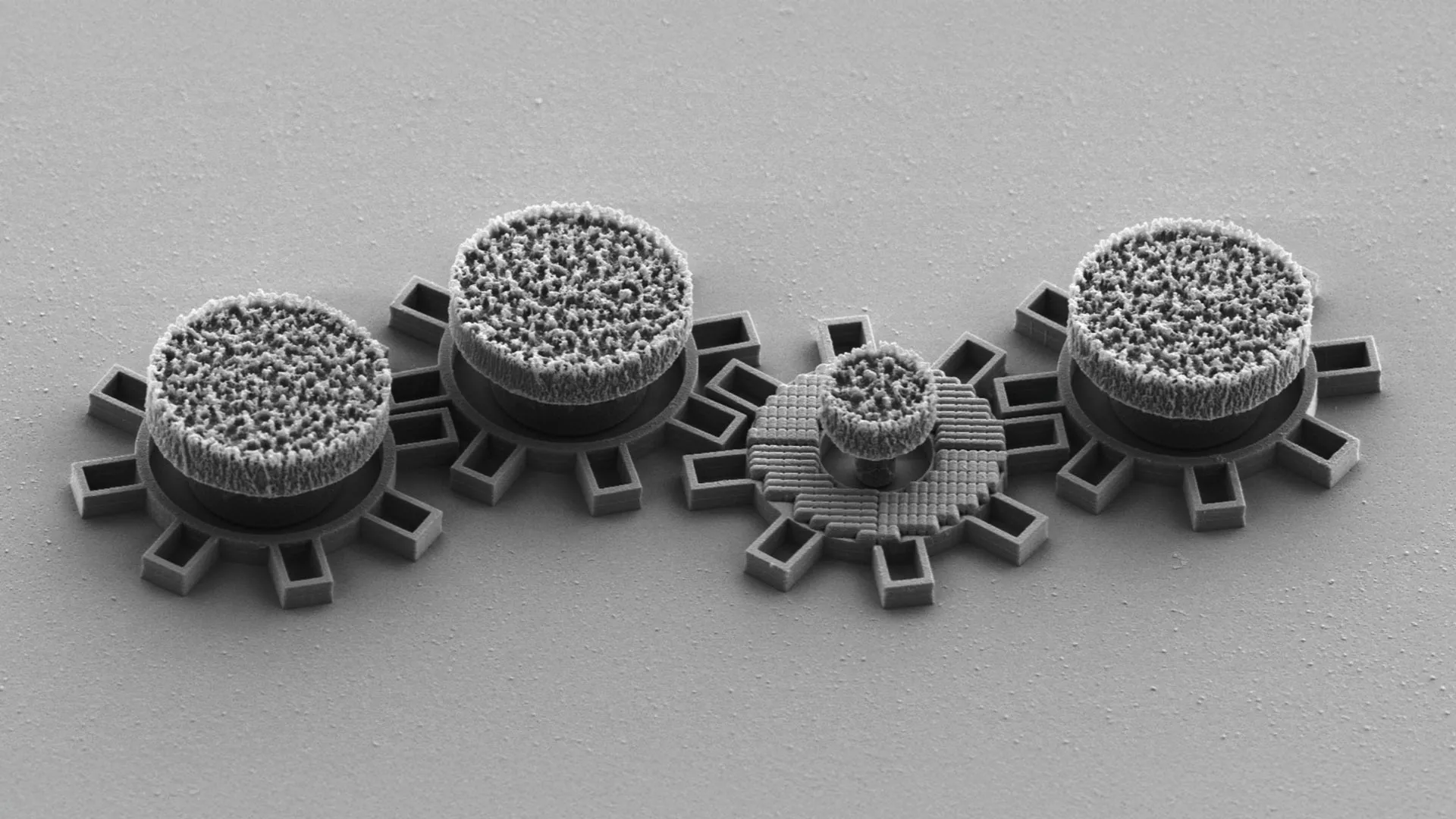

The core of this breakthrough lies in the researchers’ innovative use of optical metamaterials. These are not ordinary materials; they are meticulously engineered, small, patterned structures designed to interact with light in highly specific ways. In this instance, the metamaterials are capable of capturing and precisely controlling light on a nanoscale. Utilizing well-established lithography techniques, the researchers were able to fabricate these gears, embedded with optical metamaterials, directly onto a silicon microchip. The resulting gear wheels, a few tens of micrometers in diameter, are remarkably small, readily fitting within the width of a human hair.

The magic happens when a laser beam is directed at the metamaterial. The interaction between the light and the patterned structure causes the gear wheel to spin. Crucially, the intensity of the laser light serves as a precise control mechanism for the speed of rotation. Furthermore, the direction of the gear wheel’s spin can be manipulated by altering the polarization of the incident light. This level of fine-grained control, achieved through optical means, is what brings the researchers to the cusp of creating truly functional micromotors.

A Fundamentally New Way of Thinking About Microscale Mechanics

"We have built a gear train in which a light-driven gear sets the entire chain in motion," explains Gan Wang, the study’s first author and a researcher in soft matter physics at the University of Gothenburg. "The gears can also convert rotation into linear motion, perform periodic movements and control microscopic mirrors to deflect light." This ability to not only initiate motion but also to translate it into different forms of movement and to interact with other microscopic elements highlights the versatility of this new technology.

The profound implications of being able to integrate such intricate micro-machines directly onto a chip and power them remotely with light are vast. Unlike traditional mechanical systems that require physical connections, which are cumbersome and difficult to miniaturize, laser light offers a non-contact method of actuation that is both elegant and highly controllable. This freedom from bulky couplings is precisely what has allowed the researchers to overcome the size barrier that has long plagued micro-engineering. The ease with which light can be directed and modulated means that these micromotors can be scaled up to form incredibly complex microsystems, with a multitude of components working in concert.

"This is a fundamentally new way of thinking about mechanics on a microscale," emphasizes Gan Wang. "By replacing bulky couplings with light, we can finally overcome the size barrier." This shift in perspective, from purely mechanical interactions to light-driven actuation, represents a paradigm shift in the field of micro- and nanotechnology.

Reaching the Cell Size and Beyond: Medical and Scientific Frontiers

The current advancements have brought researchers to a point where they can envision micro- and nanomachines capable of a wide array of sophisticated tasks. These include the precise control of light, the delicate manipulation of microscopic particles, and seamless integration into the burgeoning field of future lab-on-a-chip systems. The gear wheels themselves can be as small as 16-20 micrometers in diameter, a size that is directly comparable to that of human cells. This proximity in scale immediately suggests a wealth of applications in the realm of medicine.

"Medicine is a field that is within reach," believes Gan Wang. The potential for these microscopic motors to revolutionize medical treatments and diagnostics is immense. For instance, they could be employed as incredibly precise pumps within the human body, regulating various fluid flows with unparalleled accuracy. This could be crucial for drug delivery, for managing bodily fluids in critical conditions, or for a myriad of other physiological interventions. Gan Wang is also actively exploring their functionality as valves that can precisely open and close, controlling the passage of fluids or other substances at the micro-level.

Beyond their direct medical applications, these light-powered micromotors hold promise for diagnostics. Imagine miniature robots that can navigate the bloodstream, delivering diagnostic agents or collecting tissue samples, all powered by external light sources. The ability to precisely control their movement and function within the complex environment of the human body, without the need for invasive power sources or bulky mechanical components, is a significant advantage.

The implications extend beyond internal medicine. In external medical devices, these micromotors could enable new forms of minimally invasive surgery, allowing for the manipulation of tiny instruments with extreme precision. They could also be used in advanced prosthetics, providing more nuanced and responsive movement.

The scientific community is abuzz with the potential of these tiny machines. The ability to create and control such small-scale mechanical systems opens doors to new avenues of scientific inquiry. For example, researchers could use these micromotors to build miniature experimental setups within microfluidic devices, allowing for the study of chemical reactions or biological processes at an unprecedented level of detail and control. The precise manipulation of individual cells or molecules could become a routine task.

Furthermore, the integration of these light-powered micromotors into on-chip systems suggests a future where computing and physical actuation are seamlessly intertwined at the nanoscale. This could lead to the development of novel sensors, advanced micro-robotics for manufacturing and assembly, and even new forms of data storage and processing. The ability to control these tiny machines with light also has implications for optical computing and the development of new types of optical switches and logic gates.

The University of Gothenburg’s achievement is not merely an incremental improvement; it is a fundamental breakthrough that redefines the boundaries of what is possible in micro-engineering. By cleverly leveraging the principles of light-matter interaction and optical metamaterials, these scientists have provided the world with a powerful new tool. As research progresses, we can anticipate these microscopic marvels moving from the laboratory benchtop into a wide array of practical applications, ushering in an era of unprecedented miniaturization and functional complexity. The future, it seems, is being built, one microscopic gear at a time, powered by the elegance of light.