UNSW engineers have achieved a monumental leap in quantum computing by successfully creating ‘quantum entangled states’ between two separate atomic nuclei within silicon chips. This profound connection, where the particles become so deeply intertwined they defy independent behavior, is the cornerstone of the immense power that quantum computers promise over their classical counterparts. The groundbreaking research, published on September 18th in the prestigious journal Science, marks a pivotal step towards realizing large-scale quantum computers, a challenge at the forefront of 21st-century scientific and technological ambition.

Dr. Holly Stemp, the lead author of the study, emphasized the transformative potential of this achievement, stating that it unlocks the possibility of constructing the future microchips essential for quantum computing by leveraging existing technological infrastructure and manufacturing processes. "We succeeded in making the cleanest, most isolated quantum objects talk to each other, at the scale at which standard silicon electronic devices are currently fabricated," she declared, highlighting the seamless integration of quantum capabilities with established silicon fabrication.

The persistent hurdle in quantum computer engineering has been the delicate balancing act between isolating sensitive quantum elements from the cacophony of external interference and noise, while simultaneously enabling them to interact to perform complex computations. This intricate challenge has fueled a diverse landscape of hardware approaches vying for dominance in the quantum computing race. Some systems excel at rapid operations but are susceptible to noise, while others offer superior noise resilience but face significant operational and scaling difficulties.

The UNSW team has strategically focused on a platform that, until this breakthrough, resided firmly in the latter category. Their approach encodes quantum information using the nuclear spin of phosphorus atoms meticulously implanted within a silicon chip. Scientia Professor Andrea Morello from the UNSW School of Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications explained the fundamental advantage of this strategy: "The spin of an atomic nucleus is the cleanest, most isolated quantum object one can find in the solid state." He further elaborated on the extensive groundwork laid by his group over the past 15 years, which has propelled this technology into serious contention. "We already demonstrated that we could hold quantum information for over 30 seconds – an eternity, in the quantum world – and perform quantum logic operations with less than 1% errors. We were the first in the world to achieve this in a silicon device, but it all came at a price: the same isolation that makes atomic nuclei so clean, makes it hard to connect them together in a large-scale quantum processor."

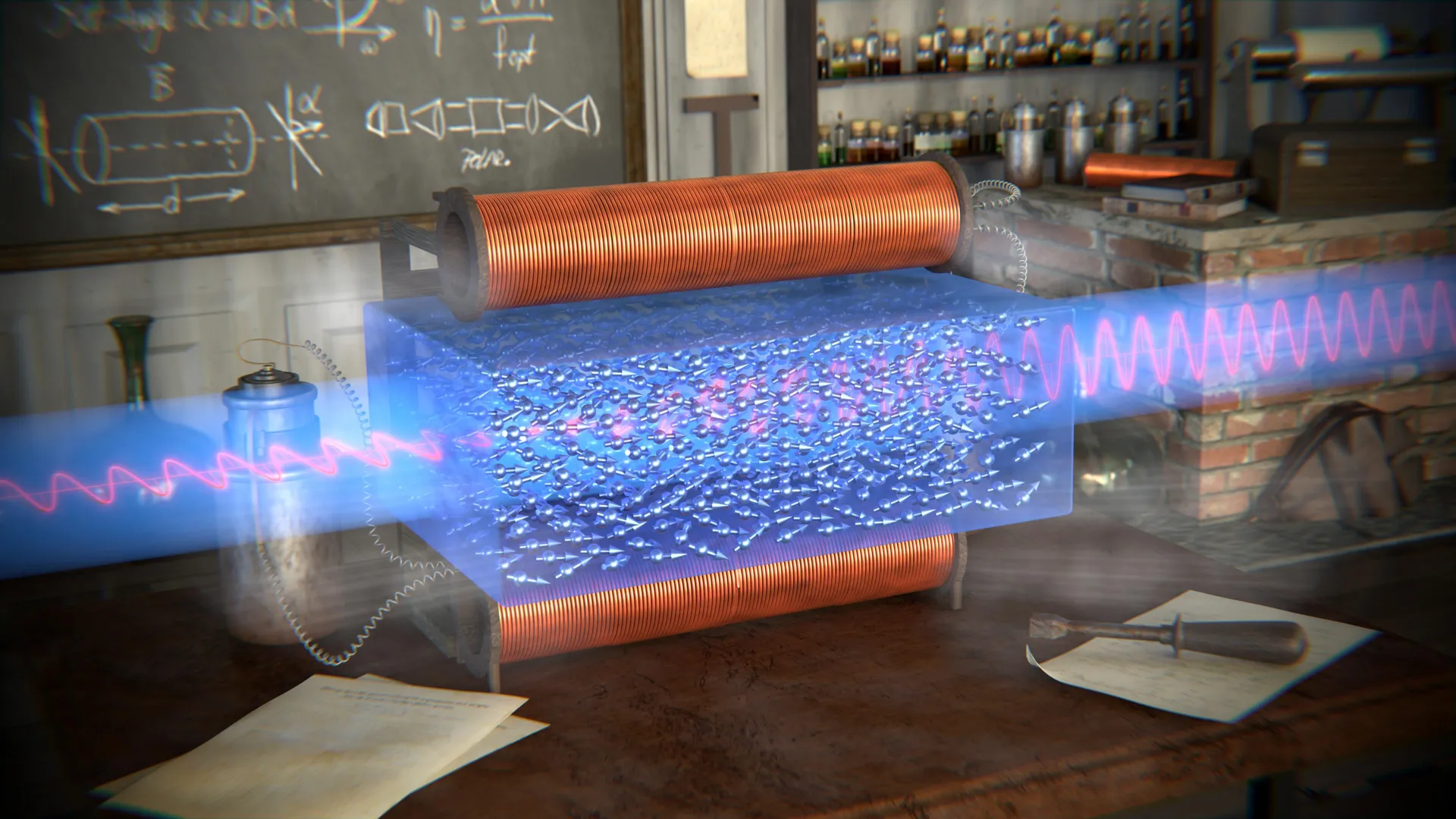

Historically, connecting multiple atomic nuclei for quantum operations necessitated their proximity, often residing within the same solid material and sharing a single electron. Dr. Stemp, who conducted this research at UNSW and is now a postdoctoral researcher at MIT, offered a fascinating insight into the quantum mechanical behavior of electrons: "Most people think of an electron as the tiniest subatomic particle, but quantum physics tells us that it has the ability to ‘spread out’ in space, so that it can interact with multiple atomic nuclei." However, she cautioned, "Even so, the range over which the electron can spread is quite limited. Moreover, adding more nuclei to the same electron makes it very challenging to control each nucleus individually."

Making Atomic Nuclei "Talk" Through Electronic ‘Telephones’

To illuminate this complex interaction, Dr. Stemp employed a compelling metaphor: "By way of metaphor, one could say that, until now, nuclei were like people placed in a sound-proof room. They can talk to each other as long as they are all in the same room, and the conversations are really clear. But they can’t hear anything from the outside, and there’s only so many people who can fit inside the room. This mode of conversation doesn’t ‘scale’."

The profound shift brought about by the UNSW breakthrough, she explained, is akin to equipping these individuals with "telephones to communicate to other rooms. All the rooms are still nice and quiet on the inside, but now we can have conversations between many more people, even if they are far away."

These "telephones," in the realm of quantum physics, are indeed electrons. Mark van Blankenstein, another key author on the paper, provided a more granular explanation of the sub-atomic mechanics at play: "By their ability to spread out in space, two electrons can ‘touch’ each other at quite some distance. And if each electron is directly coupled to an atomic nucleus, the nuclei can communicate through that."

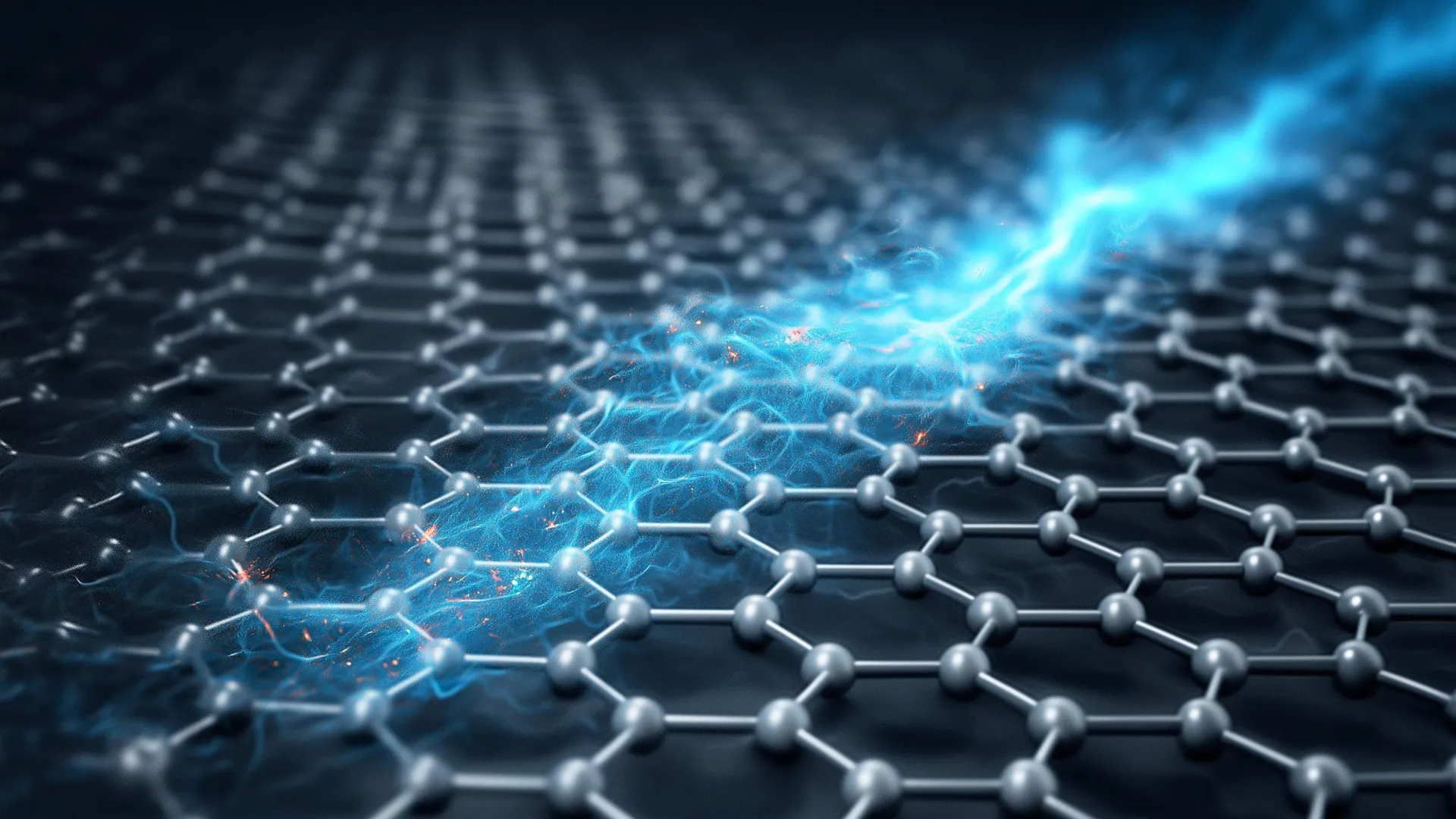

The spatial separation achieved in the experiments is particularly remarkable. "The distance between our nuclei was about 20 nanometers – one thousandth of the width of a human hair," Dr. Stemp revealed. She then offered a striking analogy to contextualize this microscopic distance: "That doesn’t sound like much, but consider this: if we scaled each nucleus to the size of a person, the distance between the nuclei would be about the same as that between Sydney and Boston!" This comparison underscores the immense progress in manipulating matter at such infinitesimal scales.

Crucially, Dr. Stemp emphasized the technological significance of this distance: "20 nanometers is the scale at which modern silicon computer chips are routinely manufactured to work in personal computers and mobile phones. You have billions of silicon transistors in your pocket or in your bag right now, each one about 20 nanometers in size. This is our real technological breakthrough: getting our cleanest and most isolated quantum objects talking to each other at the same scale as existing electronic devices. This means we can adapt the manufacturing processes developed by the trillion-dollar semiconductor industry, to the construction of quantum computers based on the spins of atomic nuclei."

A Scalable Way Forward

Despite the inherently exotic nature of quantum entanglement, the UNSW researchers underscored the fundamental compatibility of their devices with established computer chip manufacturing paradigms. The precise implantation of phosphorus atoms into the chip was a collaborative effort, involving the expertise of Professor David Jamieson’s team at the University of Melbourne and an ultra-pure silicon slab supplied by Professor Kohei Itoh at Keio University in Japan.

By liberating atomic nuclei from their reliance on being tethered to the same electron, the UNSW team has effectively dismantled the most significant impediment to the large-scale production of silicon quantum computers utilizing atomic nuclei. Professor Morello expressed optimism about the future scalability and robustness of their method: "Our method is remarkably robust and scalable. Here we just used two electrons, but in the future we can even add more electrons, and force them in an elongated shape, to spread out the nuclei even further." He concluded by highlighting the inherent advantages of electrons in this context: "Electrons are easy to move around and to ‘massage’ into shape, which means the interactions can be switched on and off quickly and precisely. That’s exactly what is needed for a scalable quantum computer." This breakthrough therefore represents not just a scientific curiosity, but a tangible pathway towards realizing the transformative potential of quantum computing within the familiar framework of silicon technology.