The genesis of this remarkable innovation can be traced back to the laboratory of Michal Lipson, a distinguished Eugene Higgins Professor of Electrical Engineering and professor of Applied Physics. Her team was initially focused on developing high-power chips designed to produce more intense light beams for LiDAR, a sophisticated technology that utilizes light waves to measure distances with remarkable accuracy. However, during their experiments, a serendipitous observation emerged. Andres Gil-Molina, a former postdoctoral researcher in Lipson’s lab and now a principal engineer at Xscape Photonics, recounts the pivotal moment: "As we sent more and more power through the chip, we noticed that it was creating what we call a frequency comb."

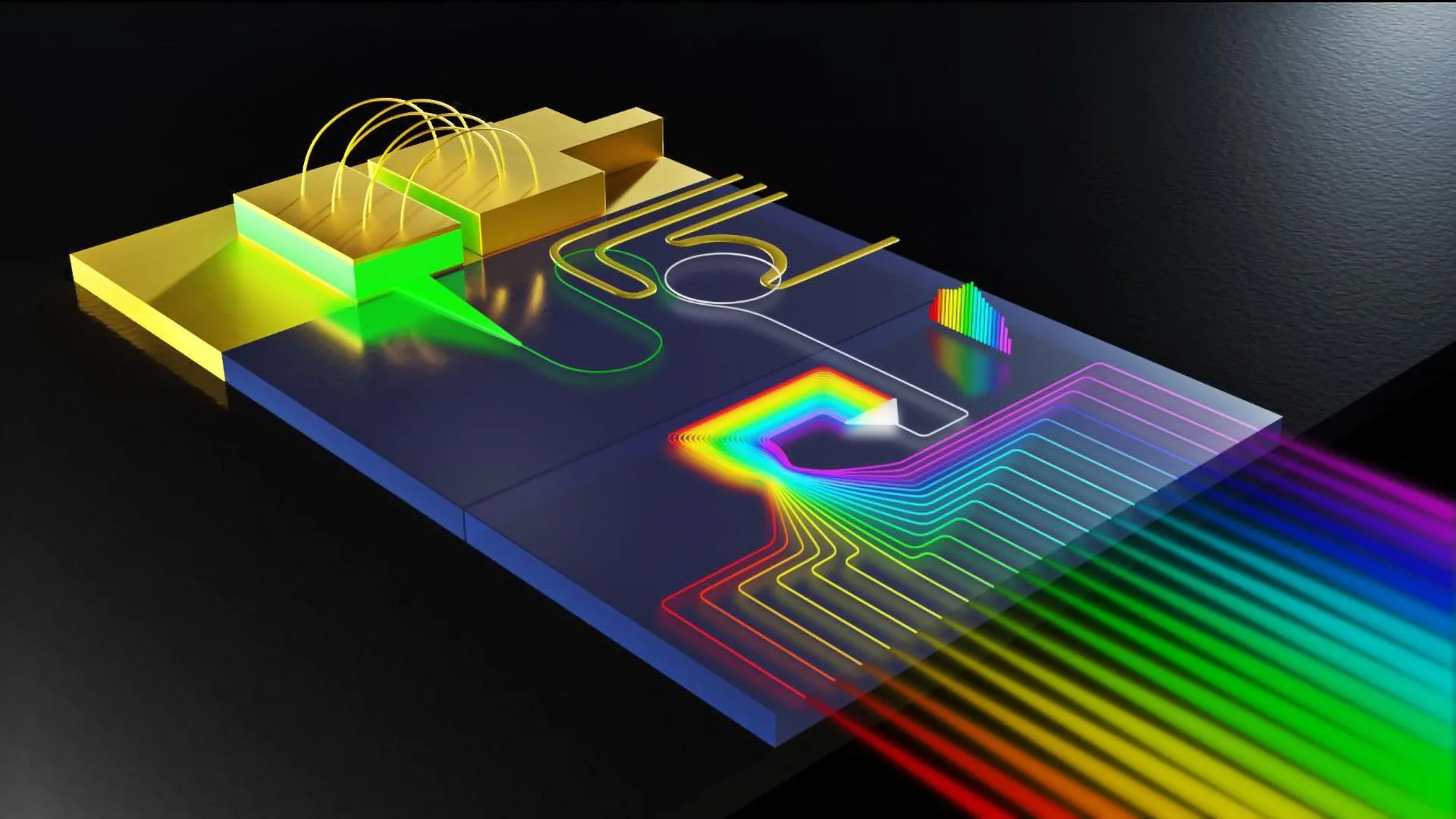

A frequency comb is not just any light; it’s a precisely structured illumination composed of numerous distinct colors, or frequencies, arranged side-by-side in a highly organized sequence. This unique characteristic is visually reminiscent of the distinct bands of color in a rainbow. Crucially, each of these individual colors shines with considerable intensity, while the spaces separating them remain conspicuously dark. When visualized on a spectrogram, these bright, discrete frequencies manifest as evenly spaced spikes, creating a pattern that strikingly resembles the teeth of a comb. This intricate arrangement is the key to its revolutionary potential: it allows for dozens, if not hundreds, of data channels to operate simultaneously. Each individual color of light within the comb can effectively carry its own independent stream of information without interfering with the others, thereby exponentially increasing the data-carrying capacity of a single optical fiber.

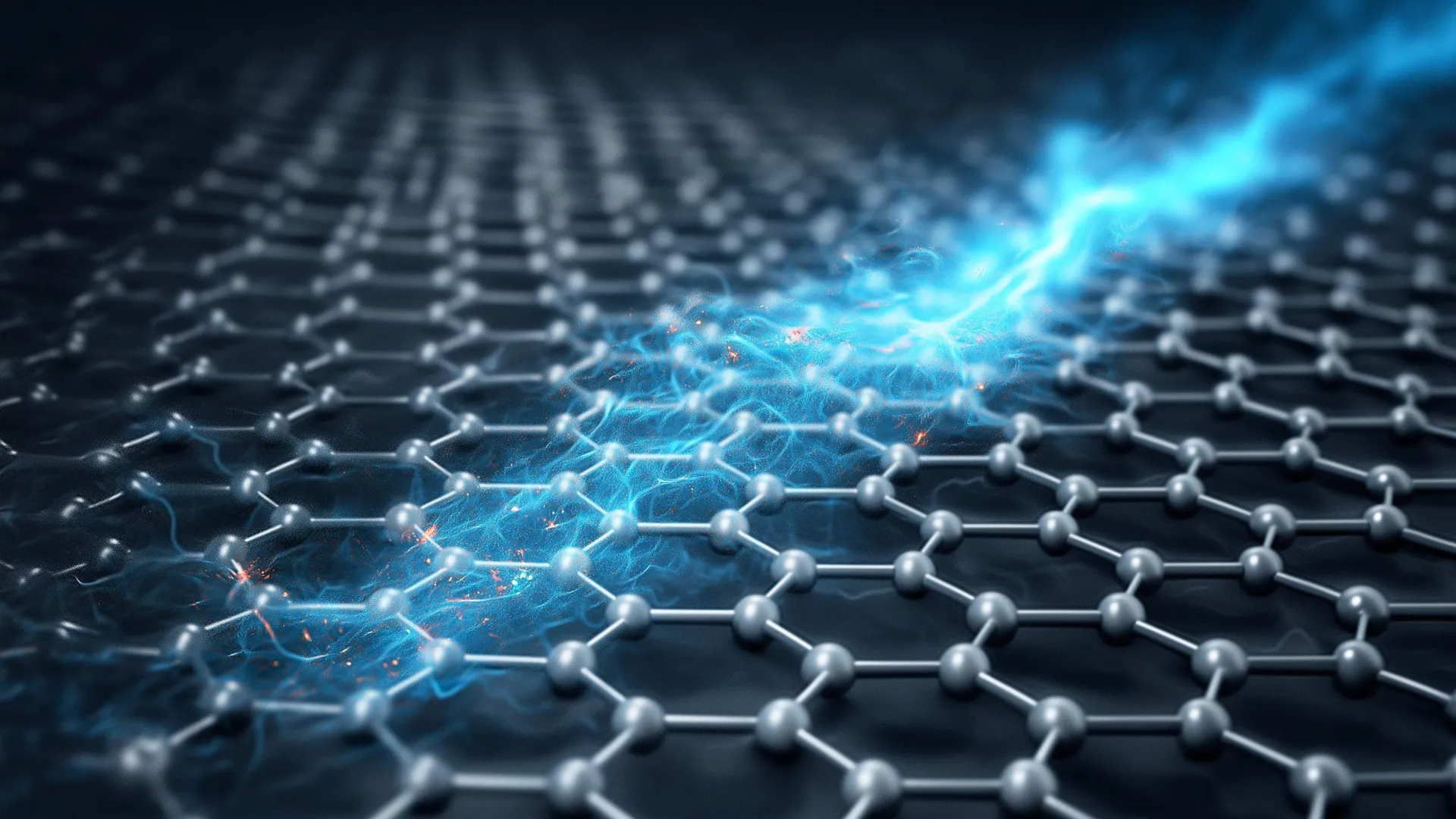

Historically, the generation of a powerful and useful frequency comb has been a complex and resource-intensive endeavor. It typically necessitates the use of bulky, expensive, and energy-hungry lasers and amplifiers. These traditional setups often occupy significant physical space and contribute to higher operational costs. However, in a pivotal new study published in the prestigious journal Nature Photonics, Lipson and her accomplished colleagues have demonstrated a paradigm shift. They have successfully achieved the same powerful frequency comb effect, but instead of relying on cumbersome external equipment, they have managed to integrate this capability onto a single, compact microchip.

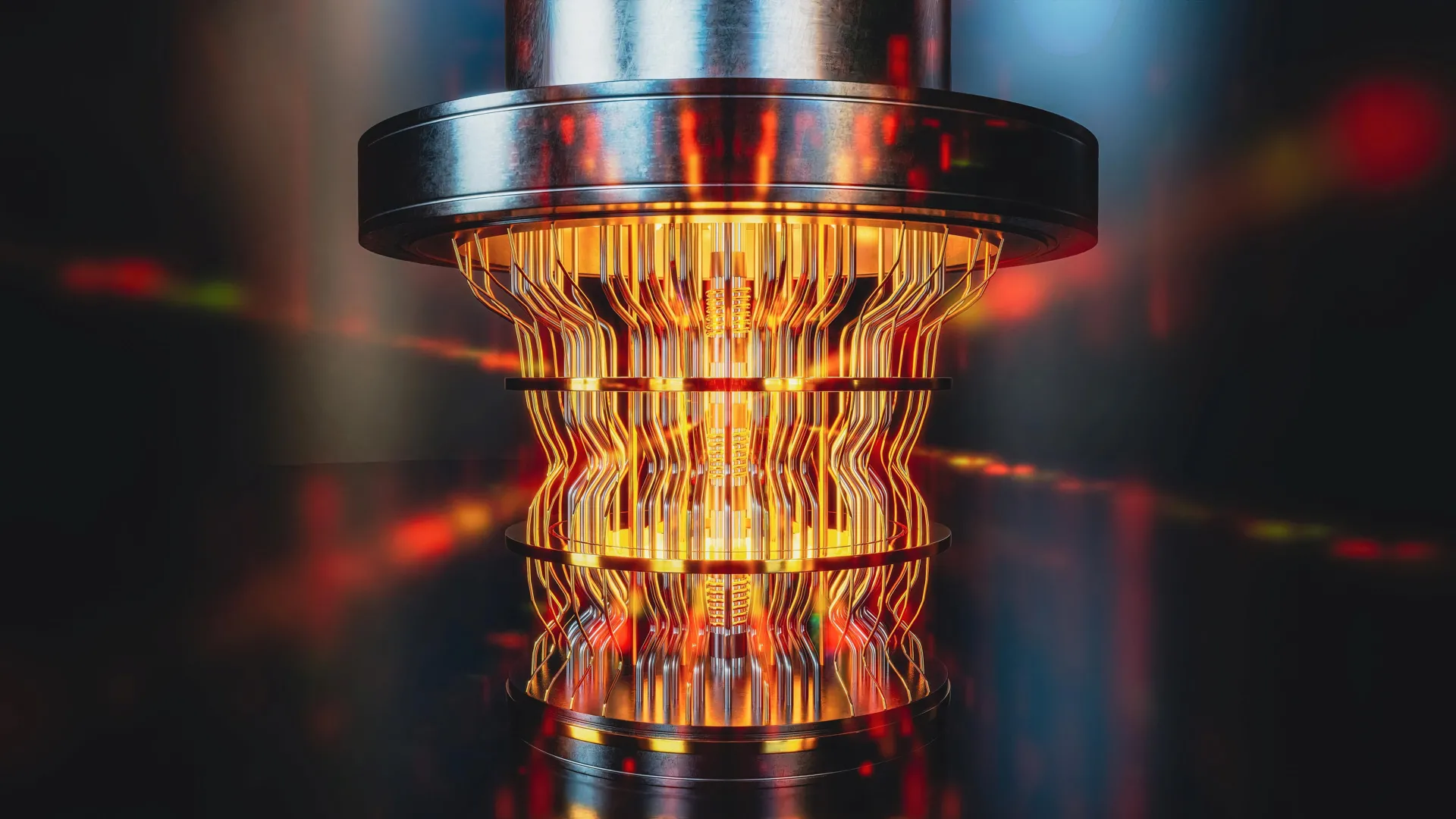

The implications of this miniaturization are profound, particularly for the burgeoning field of data centers. Gil-Molina elaborates on the critical need that this technology addresses: "Data centers have created tremendous demand for powerful and efficient sources of light that contain many wavelengths." He further explains the transformative impact of their invention: "The technology we’ve developed takes a very powerful laser and turns it into dozens of clean, high-power channels on a chip. That means you can replace racks of individual lasers with one compact device, cutting cost, saving space, and opening the door to much faster, more energy-efficient systems." This transition from large-scale infrastructure to a single, integrated chip represents a monumental leap in terms of both economic viability and operational efficiency.

Professor Lipson emphasizes the significance of this achievement within the broader context of her lab’s ongoing research: "This research marks another milestone in our mission to advance silicon photonics." She underscores the growing importance of efficient data transmission in our increasingly digitized world: "As this technology becomes increasingly central to critical infrastructure and our daily lives, this type of progress is essential to ensuring that data centers are as efficient as possible." Silicon photonics, the field that integrates electronic and optical functionalities onto silicon chips, is poised to become a cornerstone of future computing and communication technologies, and this "rainbow chip" is a testament to its immense potential.

The genesis of this remarkable breakthrough was driven by a deceptively simple yet ambitious question: "how powerful a laser could they integrate onto a chip?" This fundamental inquiry set the team on a path that would ultimately lead to the creation of their revolutionary device.

Their approach involved working with a multimode laser diode, a type of laser commonly employed in demanding industrial applications such as medicine and heavy-duty cutting tools. While these lasers are known for their ability to generate substantial amounts of light, their beams are often characterized as chaotic or "messy," meaning they lack the precise order and coherence required for sensitive and precision-oriented applications. The challenge then became how to harness this raw power within the confined and delicate environment of a silicon photonics chip, where light propagates through microscopic pathways that can be mere microns or even hundreds of nanometers in width.

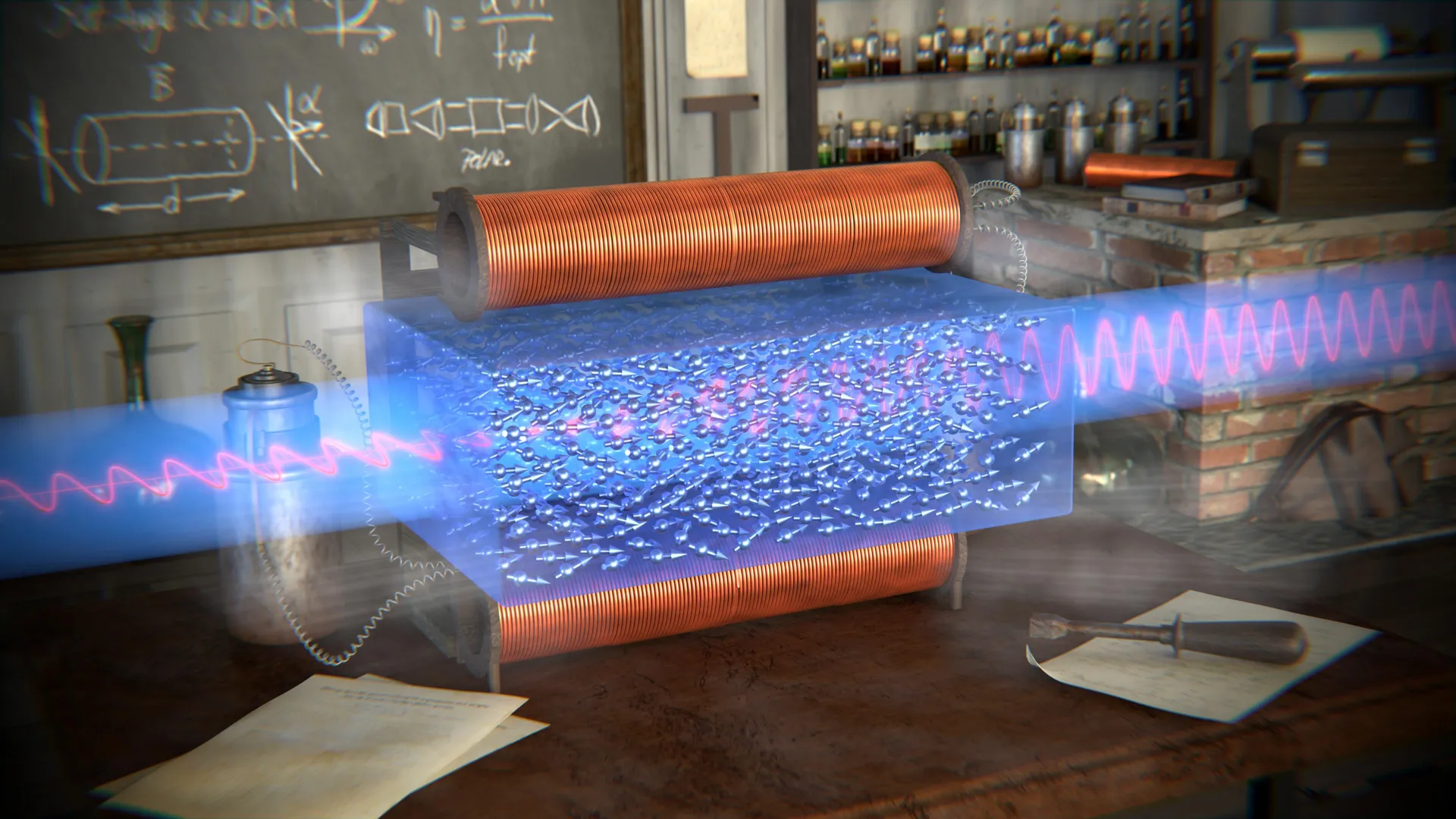

To overcome this hurdle, the team implemented an ingenious solution: "We used something called a locking mechanism to purify this powerful but very noisy source of light," Gil-Molina explains. This sophisticated method leverages the inherent capabilities of silicon photonics to meticulously reshape and refine the laser’s output. The result is a significantly cleaner, more stable, and highly ordered beam of light—a characteristic that scientists refer to as high coherence. This purification step is absolutely critical for the subsequent creation of the frequency comb.

Once the light has been meticulously purified, the chip’s intrinsic nonlinear optical properties come into play. These properties enable the chip to take the single, purified, powerful beam and effectively split it into dozens of evenly spaced colors, thus generating the defining feature of a frequency comb. The ultimate outcome of this intricate process is a light source that is not only compact and highly efficient but also combines the immense power of an industrial-grade laser with the precision and stability that are indispensable for advanced communication systems and sophisticated sensing technologies.

The timing of this breakthrough is particularly noteworthy, coinciding with a period of unprecedented growth in artificial intelligence. The insatiable demand for AI-driven applications is placing immense strain on the infrastructure within data centers, particularly in the critical task of moving information at breakneck speeds between processors and memory modules. While state-of-the-art data centers already rely on fiber optic links for data transmission, a significant limitation persists: most of these links still operate with single-wavelength lasers, meaning each fiber carries only one data stream.

Frequency combs offer a revolutionary solution to this bottleneck. Instead of a single beam carrying a single data stream, the "rainbow chip" enables dozens of distinct beams, each carrying its own independent data stream, to travel in parallel through the same optical fiber. This principle is the very foundation of wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM), the groundbreaking technology that was instrumental in transforming the internet into the global, high-speed network we know today during the late 1990s.

By successfully miniaturizing the generation of high-power, multi-wavelength frequency combs to the point where they can be integrated directly onto a chip, Lipson’s team has democratized this advanced capability. This innovation makes it feasible to incorporate this high-density data transmission technology into the most compact and cost-sensitive components of modern computing systems. Beyond the immediate benefits for data centers, the potential applications of these "rainbow chips" extend far beyond. They could pave the way for portable spectrometers, enabling rapid and precise chemical analysis; ultra-precise optical clocks, which are crucial for scientific research and navigation; compact quantum devices, opening new frontiers in computing and sensing; and even significantly advanced LiDAR systems for autonomous vehicles and environmental monitoring.

"This is about bringing lab-grade light sources into real-world devices," Gil-Molina concludes with a sense of profound optimism. "If you can make them powerful, efficient, and small enough, you can put them almost anywhere." This sentiment encapsulates the transformative power of their accidental discovery—a tiny chip, born from scientific curiosity, that holds the potential to reshape the very fabric of our digital world, ushering in an era of unparalleled speed, efficiency, and connectivity.