In a groundbreaking development that blurs the lines between laboratory innovation and biological reality, scientists have successfully achieved the implantation of human embryos into engineered uterine lining organoids, a feat that mirrors the critical first moments of natural pregnancy. This pioneering research, detailed in three significant papers published by Cell Press, represents the most accurate laboratory model to date of early human gestation, offering unprecedented insights into the complex processes of implantation and the potential to revolutionize In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) outcomes. The experiments, conducted in Beijing, with collaborations involving researchers from the United Kingdom, Spain, and the US, demonstrate a sophisticated approach to understanding the delicate dance between an embryo and the maternal uterus.

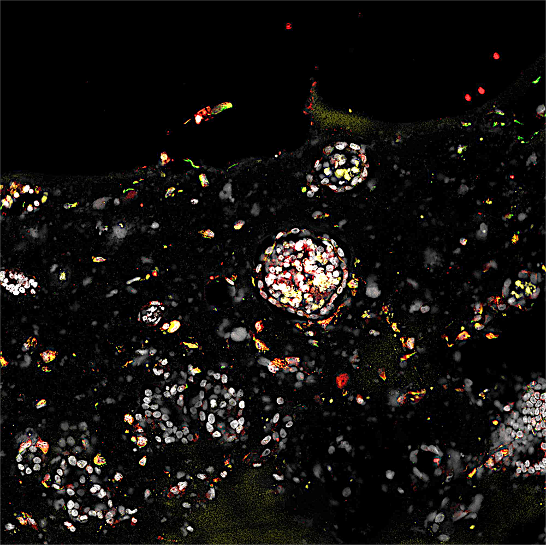

The visual representation of this scientific achievement is striking: a ball-shaped embryo gently presses against a receptive, artificially grown uterine lining, then firmly anchors itself, initiating the formation of placental structures. This process, known as implantation, marks the official commencement of pregnancy. However, these pivotal events are not unfolding within a human body, but rather within a meticulously designed microfluidic chip in a Beijing laboratory. These transparent chips, equipped with precisely measured channels, serve as miniature incubators, nurturing the organoids that mimic the uterine lining and facilitating the interaction with human embryos.

The core of this advancement lies in the creation of three-dimensional co-cultures where human embryos, sourced from IVF centers, are combined with "organoids" composed of endometrial cells, the functional layer of the uterus. These integrated systems are described by Jun Wu, a biologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who contributed to two of the Chinese reports, as the most complete re-creations of the initial days of pregnancy achieved in a lab. He emphasizes, "You have an embryo and the endometrial organoid together. That’s the overarching message of all three papers." The significance of these models extends to their potential utility in unraveling the reasons behind the frequent failures of IVF treatments, a persistent challenge in assisted reproduction.

Ethical and legal considerations impose a strict 14-day limit on the duration of such experiments, meaning these sophisticated laboratory pregnancies were terminated at or before this milestone. In a typical IVF procedure, a fertilized egg develops into a blastocyst, a spherical embryo, over several days in vitro before being transferred to a patient’s uterus. The hope is for this blastocyst to successfully implant and develop into a fetus. However, a common point of failure in IVF is the embryo’s inability to attach to the uterine wall, leading to a failed pregnancy. The new reports directly address this critical juncture by replicating the initial bond between mother and embryo in a controlled laboratory environment.

Matteo Molè, a biologist at Stanford University whose research is part of the published findings, aptly describes this advancement as moving beyond "in vitro fertilization" to "in vitro implantation." He notes, "Considering that implantation is a barrier [to pregnancy], we have the potential to increase the success rate if we can model it in the laboratory." The inherent difficulty in studying human implantation has historically been its private occurrence within the uterus. Hongmei Wang, a developmental biologist at the Beijing Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine and co-leader of the Beijing effort, highlights this challenge: "We’ve always hoped to understand human embryo implantation, but we have lacked a way to do so. It’s all happening in the uterus." Her previous research often involved studying monkeys to interrupt pregnancies and collect necessary tissues, underscoring the demand for a human-specific in vitro model.

The Beijing team’s experiments involved approximately 50 donated IVF embryos, but they also conducted over a thousand additional experiments using "blastoids." Blastoids are sophisticated mimics of early-stage human embryos, engineered from stem cells. Their advantage lies in their ease of production in large quantities and, importantly, their status as not being true embryos, thus circumventing some of the more stringent ethical regulations. Leqian Yu, the senior author of the Beijing report, poses the crucial question that drove this research: "The question was, if we have these blastoids, what can we use them for? The obvious next step was implantation. So how do you do that?"

The Beijing team’s ingenious solution involved constructing a soft silicone chamber with micro-channels. These channels are designed to deliver nutrients and provide a space for the uterine organoid to grow. Blastoids, or in some cases, real embryos, could then be introduced through a designated window, initiating the simulated pregnancy. Yu articulates the central aim of their work: "The key question we want to try to answer is what is the first cross-talk between embryo and mother. I think this is maybe the first time we can see the entire process."

The medical applications of this research are far-reaching. While not the first attempt at using organoids for such studies, the current work represents a significant leap in accuracy and sophistication. Several startup companies are already exploring the commercialization of similar systems, positioning them as tools to predict IVF success. Simbryo Technologies, based in Houston, has announced plans to offer "personalized" predictions for IVF patients by utilizing blastoids and endometrial organoids. This diagnostic approach would involve doctors taking a biopsy of a patient’s uterine lining, growing organoids from these cells, and then introducing blastoids to assess the uterus’s receptivity to implantation. A failure of the blastoids to implant could indicate a patient’s uterus is not conducive to supporting a pregnancy, offering a potential explanation for IVF failure.

The Beijing team further envisions their pregnancy organoids as a platform for identifying therapeutic drugs. They have demonstrated this potential by creating organoids from the uterine tissue of women who have experienced recurrent IVF failures. These organoids were then exposed to 1,119 approved drugs to identify any compounds that might enhance implantation. Encouragingly, several drugs showed promising effects. One such chemical, avobenzone, a common ingredient in sunscreens, significantly increased the implantation rate of blastoids from a mere 5% to approximately 25%. Yu expressed his center’s aspiration to initiate clinical trials if a suitable drug candidate is identified.

Looking ahead, the Beijing group is actively working to enhance the realism of their organoid system. Current iterations lack crucial cell types, including immune cells, and a functional blood supply. Yu’s immediate focus is on integrating blood vessels and micro-pumps into the chip device to establish a rudimentary circulatory system for the organoids. This development could allow for longer-term cultivation of blastoids or embryos, raising intriguing questions about the future capabilities of in-lab gestation.

Jun Wu acknowledges the potential implications, stating, "I think this technology does raise the possibility of growing things longer." He notes that some view this research as a potential precursor to creating babies entirely outside the body. However, Wu is quick to temper such speculation, emphasizing that incubating a human to term in a laboratory remains firmly in the realm of science fiction for the present. "This technology is certainly related to ectogenesis, or development outside the body," he concedes, "But I don’t think it’s anywhere near an artificial womb. That’s still science fiction." Nevertheless, this pioneering work marks a significant stride in our understanding of early human development and offers tangible hope for improving the lives of individuals undergoing fertility treatments.