For decades, theoretical physicists have harbored the conviction that many quantum simulations, despite their daunting complexity, could be rendered tractable with more efficient computational methods. Yet, bridging the gap between theoretical possibility and practical implementation has been a formidable hurdle. The UB team, led by Assistant Professor of Physics Jamir Marino, has now cleared a significant portion of this chasm by ingeniously expanding the capabilities of a cost-effective computational technique known as the truncated Wigner approximation (TWA). This method acts as a sophisticated "shortcut" in the labyrinthine world of quantum mathematics, simplifying calculations without sacrificing essential accuracy. By enhancing TWA, the researchers have unlocked the potential to tackle quantum systems that were previously thought to be exclusively within the purview of immense computing power.

The significance of their achievement is amplified by the practical nature of their innovation. The study, published in the esteemed journal PRX Quantum in September, presents not just a theoretical leap but a tangible, user-friendly TWA framework. This framework empowers researchers to input their quantum data and, remarkably, obtain meaningful results within a matter of hours, a stark contrast to the days or even weeks previously required. "Our approach offers a significantly lower computational cost and a much simpler formulation of the dynamical equations," explains Dr. Marino, the study’s corresponding author. "We think this method could, in the near future, become the primary tool for exploring these kinds of quantum dynamics on consumer-grade computers." Dr. Marino, who joined UB this fall, initiated this pioneering work during his tenure at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany. His collaborative efforts were further bolstered by his former students at Mainz, Hossein Hosseinabadi and Oksana Chelpanova, the latter now a postdoctoral researcher diligently continuing this research in Marino’s lab at UB. The foundational support for this transformative research was generously provided by esteemed institutions, including the National Science Foundation, the German Research Foundation, and the European Union, underscoring the global importance of this scientific endeavor.

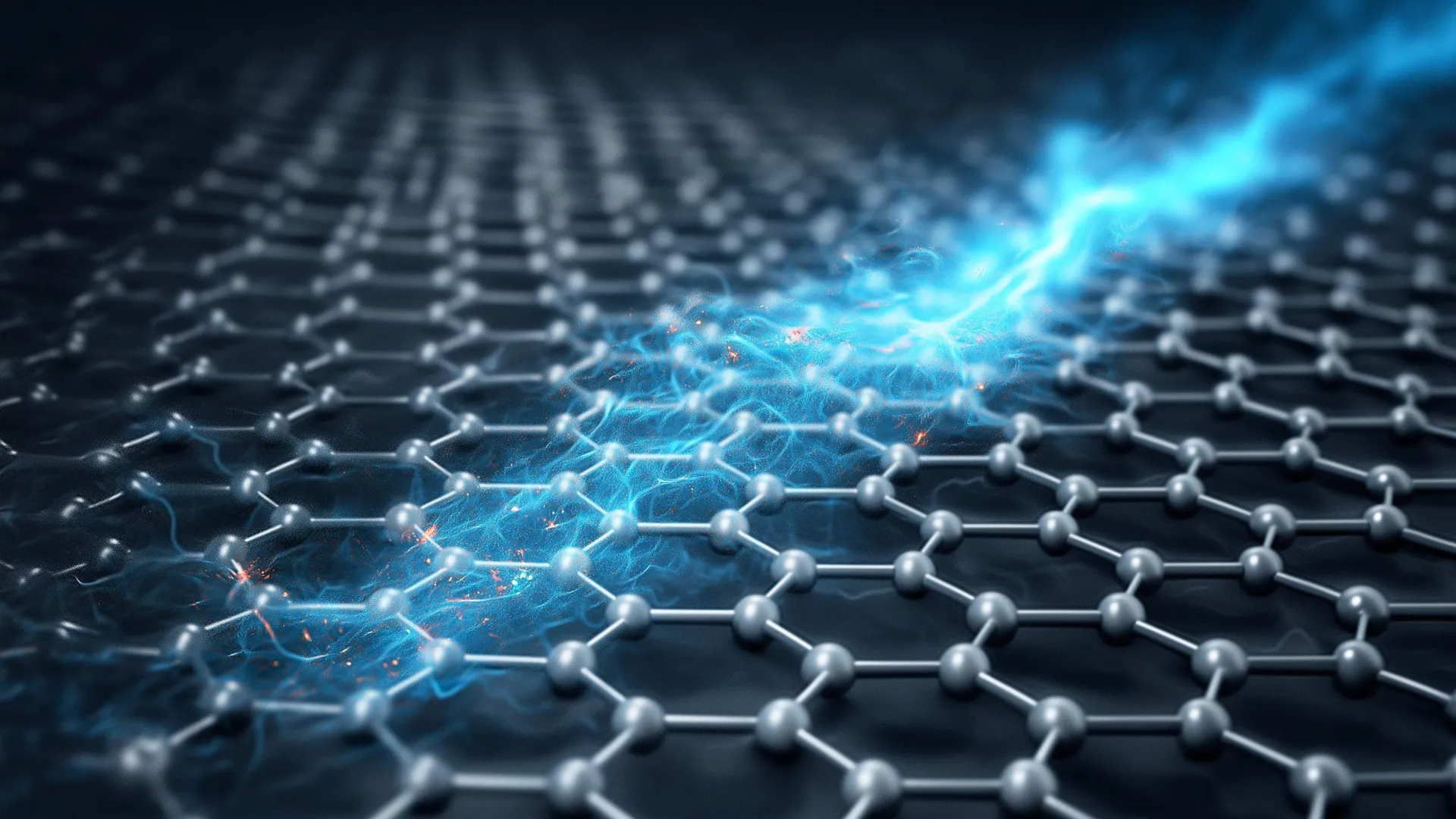

The core of the breakthrough lies in the researchers’ embrace of a "semiclassical approach." It’s a widely acknowledged reality in physics that not every quantum system can be solved with exactitude. The computational resources required to model such systems grow exponentially with their complexity, rendering exact solutions practically unattainable for all but the simplest cases. To circumvent this limitation, physicists often resort to semiclassical physics – a pragmatic middle ground that retains just enough quantum mechanical essence to ensure accuracy while judiciously discarding finer details that have a negligible impact on the overall outcome.

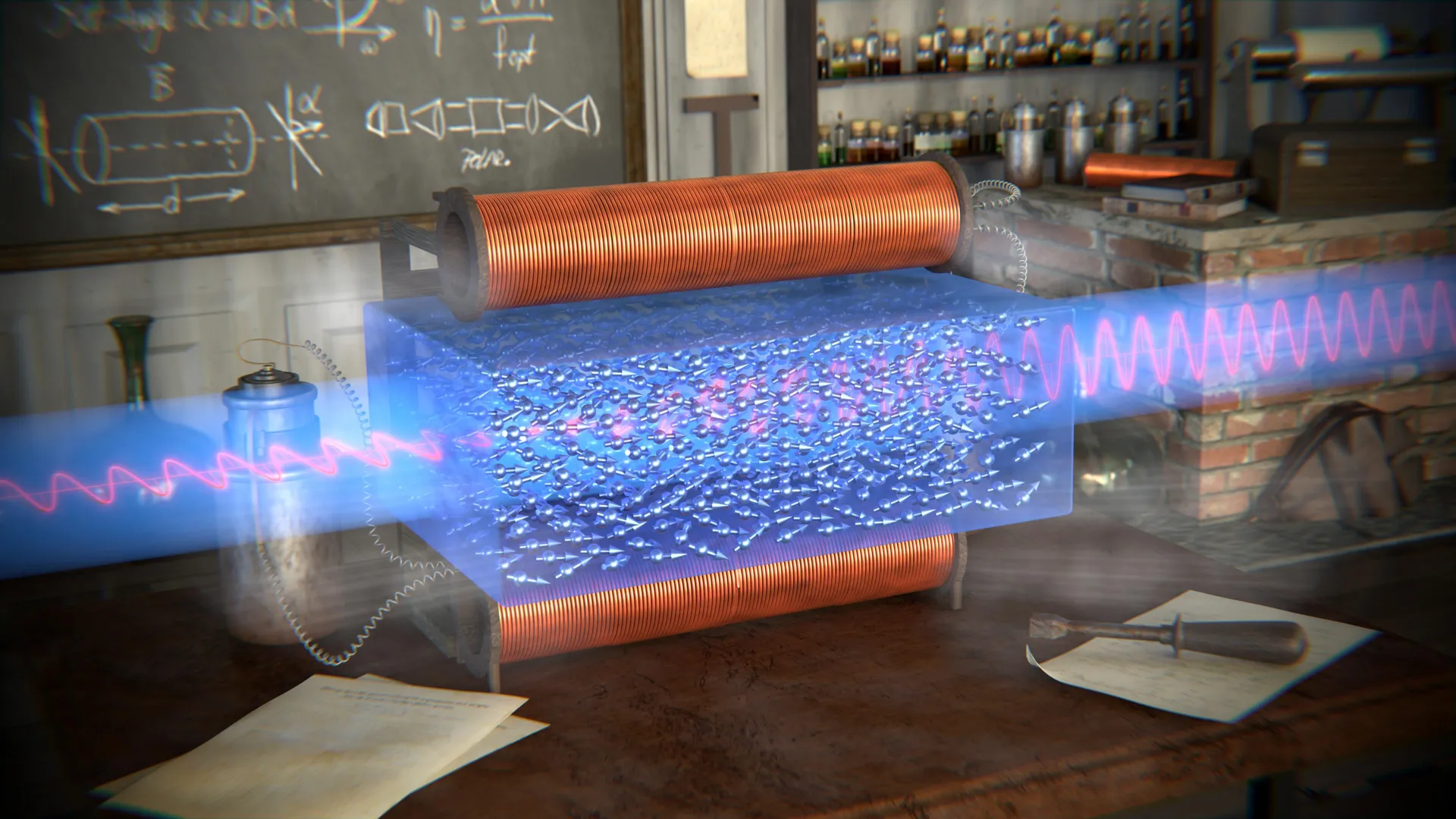

The truncated Wigner approximation (TWA) itself is a well-established semiclassical approach, originating from the 1970s. However, its utility was historically confined to isolated, idealized quantum systems – scenarios where no energy is exchanged with the external environment. This limitation meant that TWA struggled to accurately model the more complex and realistic scenarios encountered in the real world, where particles are perpetually influenced by external forces and inevitably lose energy to their surroundings. This phenomenon, known as dissipative spin dynamics, is ubiquitous in many physical systems. Marino’s team has ingeniously extended TWA to encompass these "messier" systems, thereby broadening its applicability to a far wider range of scientific investigations.

"Plenty of groups have tried to do this before us," Dr. Marino elaborates. "It’s known that certain complicated quantum systems could be solved efficiently with a semiclassical approach. However, the real challenge has been to make it accessible and easy to do." This accessibility is precisely what the UB team has achieved. Previously, researchers wishing to employ TWA would face a daunting task: they had to meticulously re-derive the underlying mathematical framework from scratch for every new quantum problem they tackled. This bespoke approach was not only time-consuming but also a significant barrier to entry for many aspiring quantum physicists.

The UB researchers have elegantly transformed this arduous process into a remarkably straightforward one. They have effectively distilled complex, often pages-long, dense mathematical formulations into a simple "conversion table." This table acts as a translator, enabling a direct mapping of a quantum problem into a set of solvable equations. "Physicists can essentially learn this method in one day, and by about the third day, they are running some of the most complex problems we present in the study," exclaims Chelpanova, highlighting the pedagogical and practical ease of their new framework. This dramatic reduction in the learning curve and implementation effort is a monumental step towards democratizing advanced quantum simulations.

The ultimate aspiration behind this innovation is to judiciously allocate precious supercomputing resources. By enabling laptops to handle a significant portion of quantum simulations, the UB team aims to free up supercomputer clusters and sophisticated AI models for the truly intractable problems. These are the systems that defy even the most advanced semiclassical approaches, systems possessing not merely a trillion possible states, but states numbering more than all the atoms in the known universe. "A lot of what appears complicated isn’t actually complicated," Dr. Marino emphasizes. "Physicists can use supercomputing resources on the systems that need a full-fledged quantum approach and solve the rest quickly with our approach." This strategic allocation will accelerate progress across a multitude of scientific disciplines, from materials science and drug discovery to fundamental physics and cosmology. The ability to simulate complex quantum phenomena on readily available hardware promises to foster a new generation of researchers equipped with powerful tools, driving innovation and deepening our understanding of the universe at its most fundamental level. The quantum realm, once a distant and computationally expensive frontier, is now becoming increasingly accessible, thanks to the ingenuity and dedication of scientists like those at the University at Buffalo.