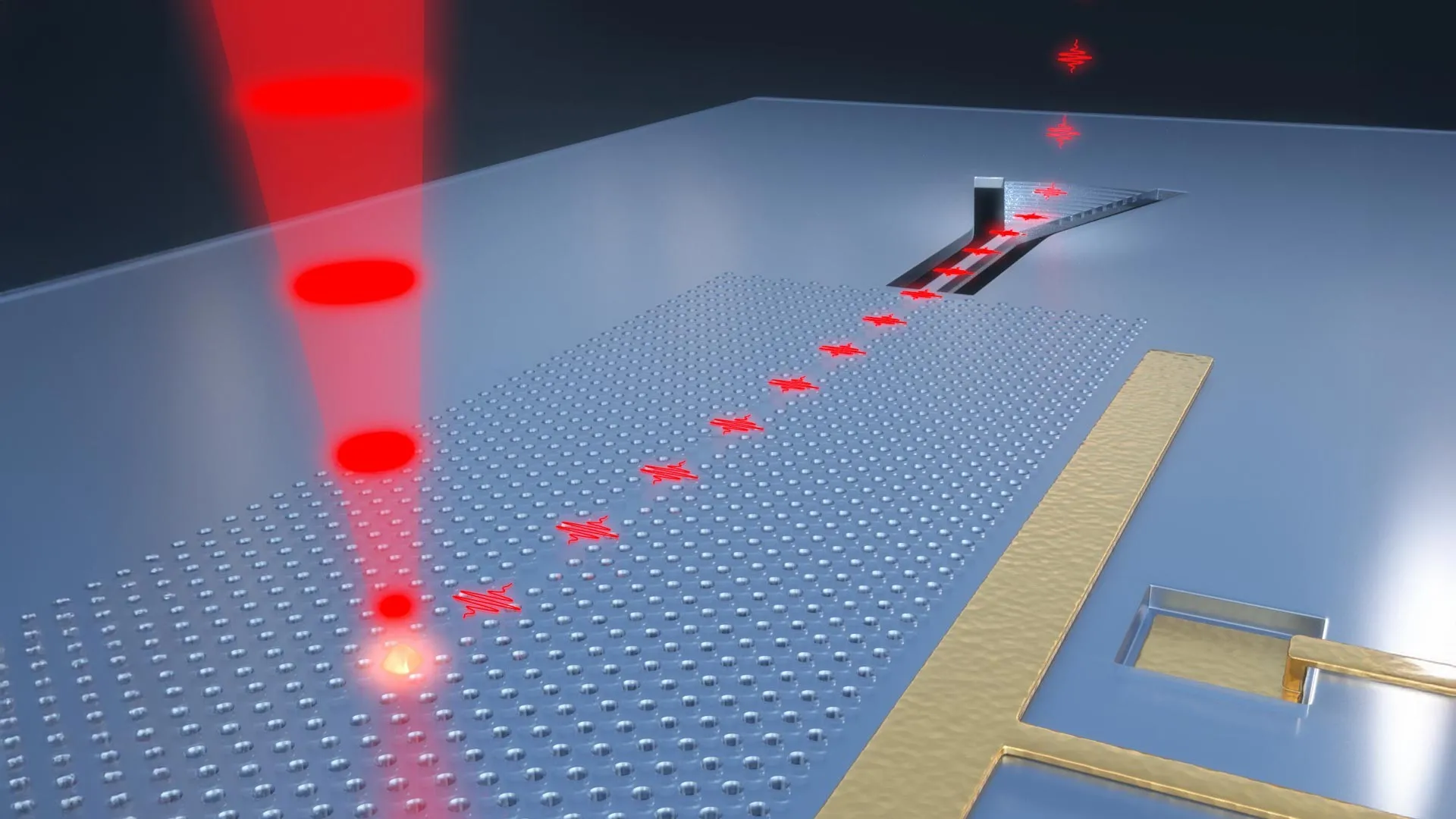

Imagine diving deep into the quantum realm, where unimaginably small particles can exist and interact in more than a trillion possible ways at the same time. This is the realm of quantum mechanics, a field that governs the fundamental fabric of reality. The behavior of atoms, molecules, and subatomic particles operates under rules that defy our everyday intuition. Unlike classical physics, where an object has a definite position and momentum, quantum particles can exist in multiple states simultaneously – a phenomenon known as superposition. Furthermore, these particles can become entangled, meaning their fates are intertwined, regardless of the distance separating them. Understanding these complex interactions and their myriad possibilities is crucial for developing new technologies and unraveling the universe’s deepest mysteries.

However, the sheer complexity of quantum systems presents a formidable challenge for physicists. As the number of interacting particles increases, the number of possible configurations grows exponentially. To model even a moderately sized quantum system, the computational power required can quickly overwhelm even the most advanced classical computers. This has historically necessitated the use of massive supercomputing clusters, often requiring weeks or months of processing time. Alternatively, researchers have turned to sophisticated artificial intelligence algorithms, which can learn patterns and make predictions, but still require substantial computational resources and expertise to develop and implement effectively.

For decades, scientists have theorized that a more efficient approach might be possible, one that leverages approximations to simplify the complex quantum mathematics without sacrificing crucial accuracy. The challenge has been to translate this theoretical possibility into a practical and accessible computational technique. Now, researchers at the University at Buffalo have made a significant leap forward by expanding a cost-effective computational method known as the truncated Wigner approximation (TWA).

The truncated Wigner approximation, first developed in the 1970s, is a type of physics "shortcut" that simplifies the notoriously difficult quantum equations. It operates on a semiclassical principle, blending elements of classical and quantum physics. In essence, TWA approximates the quantum system using classical-like trajectories, but with a crucial quantum flavor that captures the essential quantum effects. This approach has the potential to dramatically reduce the computational burden compared to full quantum mechanical calculations. However, its application has historically been limited to isolated, idealized quantum systems where no energy is exchanged with the environment.

The University at Buffalo team, led by Assistant Professor of Physics Jamir Marino, has successfully extended the TWA framework to handle more realistic and complex quantum systems. Their innovation lies in adapting TWA to account for dissipative spin dynamics, a common phenomenon in real-world quantum systems where particles are constantly influenced by external forces and lose energy to their surroundings. This expansion is critical because most interesting quantum phenomena, such as those in condensed matter physics or quantum chemistry, involve interactions with an environment. By incorporating these dissipative effects, the researchers have made TWA applicable to a much wider range of scientific problems.

"Plenty of groups have tried to do this before us," explains Marino. "It’s known that certain complicated quantum systems could be solved efficiently with a semiclassical approach. However, the real challenge has been to make it accessible and easy to do."

This is where the practical brilliance of the University at Buffalo team’s work shines. Beyond expanding the theoretical capabilities of TWA, they have also developed a user-friendly framework that simplifies its application. In the past, researchers attempting to use TWA often had to painstakingly re-derive the underlying mathematical equations from scratch for each new quantum problem they encountered. This was a time-consuming and error-prone process, effectively creating a significant barrier to entry.

Marino and his team have transformed this daunting mathematical hurdle into a straightforward process. They have developed a system that essentially acts as a "conversion table," translating a quantum problem into a set of solvable equations that can be handled by the expanded TWA. This means that instead of grappling with pages of dense, complex mathematics, physicists can now input their data and obtain meaningful results much more efficiently.

"Our approach offers a significantly lower computational cost and a much simpler formulation of the dynamical equations," says Marino. "We think this method could, in the near future, become the primary tool for exploring these kinds of quantum dynamics on consumer-grade computers."

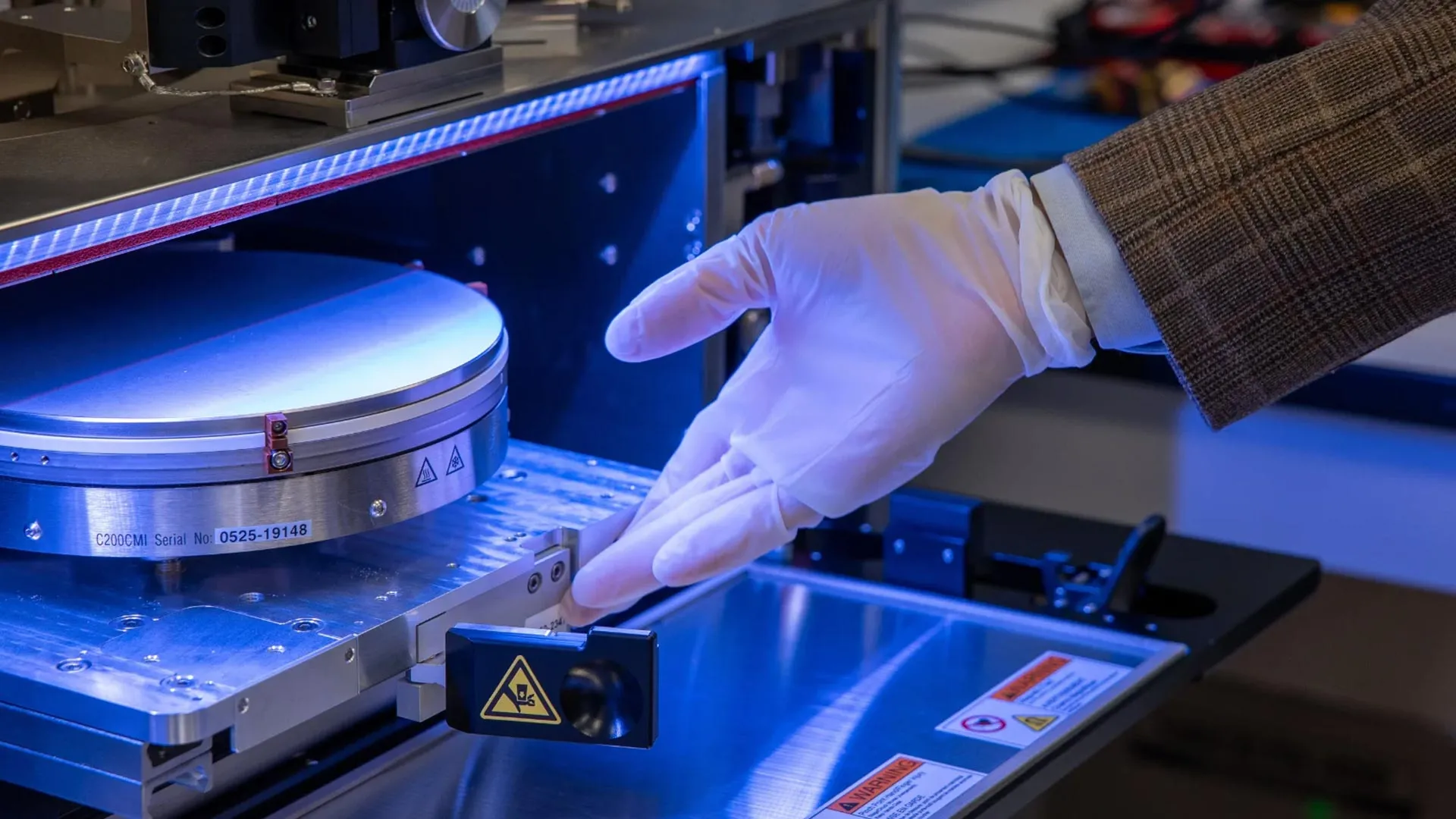

The impact of this development is profound. It means that research that once required access to expensive and limited supercomputing resources can now be conducted by individual scientists or smaller research groups using readily available hardware. This democratization of quantum simulation has the potential to accelerate discovery across numerous scientific disciplines. For instance, materials scientists could use this method to design novel materials with specific electronic or magnetic properties. Quantum chemists could explore the intricacies of chemical reactions with unprecedented detail. And researchers working on the development of quantum computers could use these simulations to test and refine their designs.

The study, published in September in PRX Quantum, a prestigious journal of the American Physical Society, outlines the methodology and demonstrates its effectiveness on several complex quantum systems. The researchers report that physicists can learn this method in about a day, and within three days, they can be running simulations of some of the most complex problems. This rapid learning curve further underscores the accessibility of their approach.

Marino, who joined UB this fall, began this work during his time at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany. His collaborators on the project include two of his former students from Mainz, Hossein Hosseinabadi and Oksana Chelpanova. Chelpanova is now a postdoctoral researcher in Marino’s lab at UB, continuing the collaborative spirit of this groundbreaking research. The project received crucial support from the National Science Foundation, the German Research Foundation, and the European Union, highlighting the international recognition and importance of this work.

The hope is that this new, accessible method will allow supercomputing clusters and AI models to be reserved for the truly intractable quantum systems – those with an astronomical number of states that cannot be approximated by semiclassical methods. These are systems so complex that they possess more possible configurations than there are atoms in the universe. By offloading the more manageable quantum dynamics problems to laptops, researchers can optimize their use of powerful computational resources.

"A lot of what appears complicated isn’t actually complicated," Marino emphasizes. "Physicists can use supercomputing resources on the systems that need a full-fledged quantum approach and solve the rest quickly with our approach." This strategic allocation of computational power ensures that the most challenging frontiers of quantum physics remain accessible for exploration, while simultaneously enabling a broader range of researchers to contribute to our understanding of the quantum world. The University at Buffalo’s innovation represents a significant stride towards making the complex language of quantum mechanics more comprehensible and actionable for scientists worldwide.