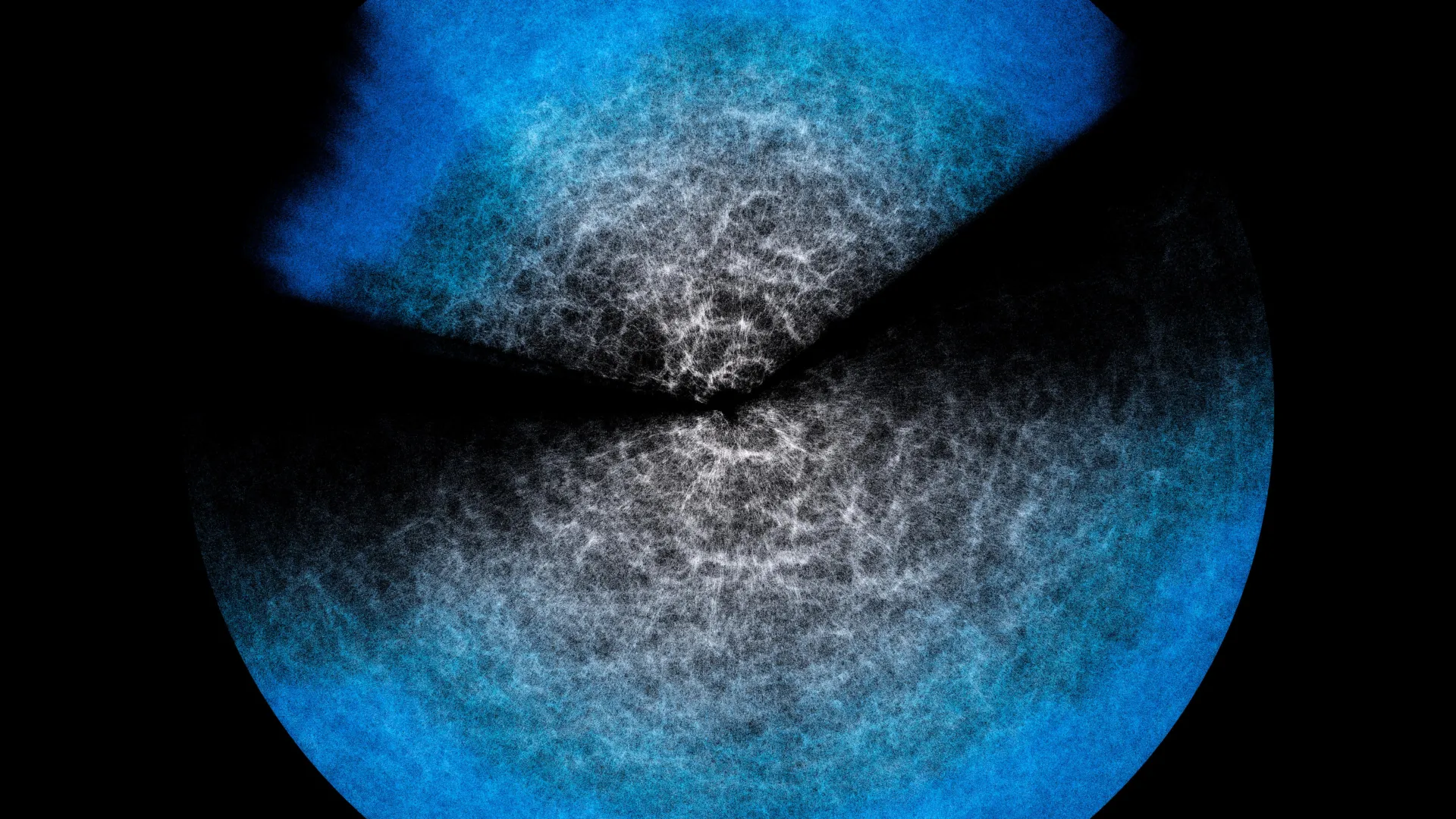

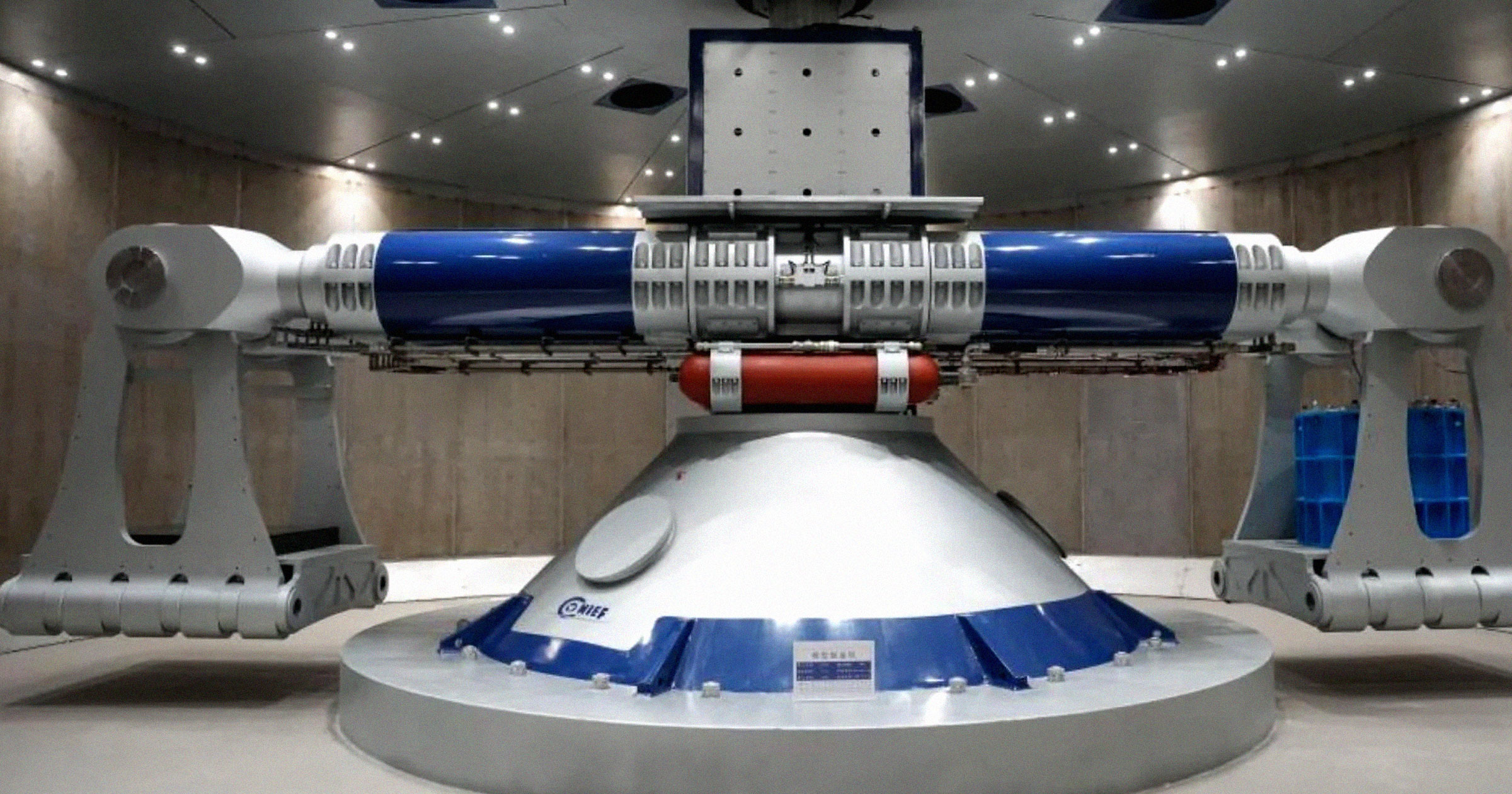

Picture diving deep into the quantum realm, where unimaginably small particles can exist and interact in more than a trillion possible ways at the same time. This is a universe of mind-bending complexity, a realm governed by probabilities and superposition, where the very fabric of reality behaves in ways that defy our everyday intuition. For decades, physicists have strived to understand these enigmatic systems, to unravel the intricate dance of quantum particles and predict their behavior. The sheer number of possible configurations, the exponential growth of complexity as systems expand, has historically relegated the study of many quantum phenomena to the exclusive domain of supercomputers and advanced artificial intelligence. These behemoths of computation, costing millions and consuming vast amounts of energy, were the only tools capable of grappling with the daunting mathematical challenges posed by quantum mechanics. However, a groundbreaking development from researchers at the University at Buffalo is poised to democratize quantum exploration, bringing the power of sophisticated quantum simulations out of the hushed halls of high-performance computing centers and onto the desks of ordinary scientists – running on nothing more than a standard laptop.

This paradigm shift is the result of a significant advancement in a cost-effective computational technique known as the truncated Wigner approximation (TWA). For years, TWA has served as a valuable "shortcut" in physics, a clever way to simplify the notoriously complex mathematics of quantum mechanics. It offers a semiclassical approach, a middle ground that retains enough quantum essence to remain accurate for many problems while shedding the computational burden of purely quantum calculations. The theoretical underpinnings of TWA suggested its potential for broader application, but translating this potential into practical, widespread use had remained an elusive goal. The primary limitation of earlier TWA methods was their restriction to isolated, idealized quantum systems – scenarios where energy exchange with the environment was negligible. This meant that many real-world quantum systems, those constantly interacting with their surroundings and experiencing energy dissipation, were beyond the reach of TWA’s simplifying power.

The University at Buffalo team, led by Assistant Professor of Physics Jamir Marino, has successfully expanded the capabilities of TWA to encompass these more realistic, "messier" systems. Their innovative approach allows TWA to handle dissipative spin dynamics, a crucial aspect of quantum behavior in many physical phenomena, including the behavior of magnetic materials and the dynamics of chemical reactions. This expansion is not merely an incremental improvement; it represents a significant leap forward, unlocking the ability to study systems previously thought to demand the immense computational muscle of supercomputers.

What makes this research particularly impactful is not just the expanded capability of the TWA, but also its newfound accessibility. The study, published in the September issue of PRX Quantum, a prestigious journal of the American Physical Society, details a practical and user-friendly TWA framework. This framework dramatically simplifies the process for researchers, allowing them to input their specific quantum system data and obtain meaningful results within a matter of hours, rather than days or weeks of intensive computation.

"Our approach offers a significantly lower computational cost and a much simpler formulation of the dynamical equations," explained Jamir Marino, the study’s corresponding author. "We think this method could, in the near future, become the primary tool for exploring these kinds of quantum dynamics on consumer-grade computers." This statement encapsulates the transformative potential of their work: making cutting-edge quantum research accessible to a much wider audience of scientists, independent of their institution’s access to supercomputing resources.

Marino, who joined UB this fall, initiated this research during his time at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany. His collaborators on this pivotal study include two of his former students from that period, Hossein Hosseinabadi and Oksana Chelpanova. Chelpanova has since joined Marino’s lab at UB as a postdoctoral researcher, continuing the collaborative spirit that fostered this breakthrough. The research was bolstered by significant financial support from esteemed institutions, including the National Science Foundation, the German Research Foundation, and the European Union, underscoring the perceived importance and potential impact of this work.

The core of the challenge in quantum physics lies in the exponential growth of complexity. As the number of particles or degrees of freedom in a quantum system increases, the number of possible states grows exponentially. Exactly solving the quantum mechanical equations for such systems quickly becomes computationally intractable, even for the most powerful supercomputers. This is where semiclassical physics, and TWA in particular, enters the picture. By cleverly approximating certain quantum behaviors and focusing on the most significant interactions, semiclassical methods can provide accurate insights without the overwhelming computational demands.

TWA, in its original form, was a powerful tool for idealized systems, but its limitations became apparent when applied to the complex, dynamic environments found in the real world. The expansion of TWA to include dissipative spin dynamics is akin to developing a more robust and versatile tool that can handle a wider range of real-world challenges. Instead of being confined to perfectly insulated quantum boxes, researchers can now use TWA to explore systems that are constantly exchanging energy with their surroundings, a far more common scenario in experimental physics and materials science.

"Plenty of groups have tried to do this before us. It’s known that certain complicated quantum systems could be solved efficiently with a semiclassical approach," Marino acknowledged. "However, the real challenge has been to make it accessible and easy to do." This highlights a common hurdle in scientific advancement: the gap between theoretical possibility and practical implementation. The University at Buffalo team has not only pushed the theoretical boundaries but has also engineered a solution that bridges this crucial gap.

The key to this newfound accessibility lies in their innovative approach to the mathematical formulation of TWA. Previously, researchers using TWA often had to embark on a laborious process of re-deriving the complex mathematical equations from scratch for each new quantum problem they investigated. This presented a significant barrier to entry, requiring deep expertise in both quantum mechanics and advanced mathematical techniques. The Buffalo team has transformed this daunting task into a straightforward conversion process. They have essentially created a "translation table" that allows a physicist to convert a quantum problem into a set of solvable equations that TWA can handle.

"Physicists can essentially learn this method in one day, and by about the third day, they are running some of the most complex problems we present in the study," stated Oksana Chelpanova, offering a testament to the method’s user-friendliness. This rapid learning curve is a game-changer, empowering graduate students, postdocs, and even established researchers to incorporate advanced quantum simulation techniques into their work without years of specialized training.

The ultimate vision behind this development is to judiciously allocate computational resources. Supercomputers and sophisticated AI models will remain indispensable for tackling the most extreme quantum problems – those involving systems with an astronomical number of states, far exceeding even the number of atoms in the universe. However, for a vast array of "lesser" quantum problems, which still present significant challenges but do not require the absolute pinnacle of computational power, the new TWA method offers an efficient and accessible alternative.

"A lot of what appears complicated isn’t actually complicated," Marino emphasized. "Physicists can use supercomputing resources on the systems that need a full-fledged quantum approach and solve the rest quickly with our approach." This pragmatic approach promises to accelerate scientific discovery across numerous fields. By freeing up supercomputing clusters for the truly intractable problems, and by enabling laptop-based simulations for a wide range of others, the new TWA framework democratizes access to quantum simulation, fosters collaboration, and ultimately, speeds up the pace of scientific innovation. The quantum realm, once a distant frontier accessible only to a select few with access to immense computing power, is now opening its doors to a much broader community of explorers, thanks to this revolutionary advancement.