Electricity, the invisible lifeblood of our modern world, powers everything from the smartphones in our pockets to the complex machinery that drives industry and innovation. This ubiquitous force is generated by the ceaseless, microscopic dance of electrons, particles so minuscule they elude our direct gaze. In conventional conductors, their collective movement through circuits mirrors the smooth, predictable flow of water through a pipe, an analogy that has long served to demystify the fundamental principles of electrical current. However, the realm of quantum mechanics offers a far more intricate and fascinating landscape, where the behavior of these fundamental particles can defy our everyday intuitions and unlock entirely new possibilities.

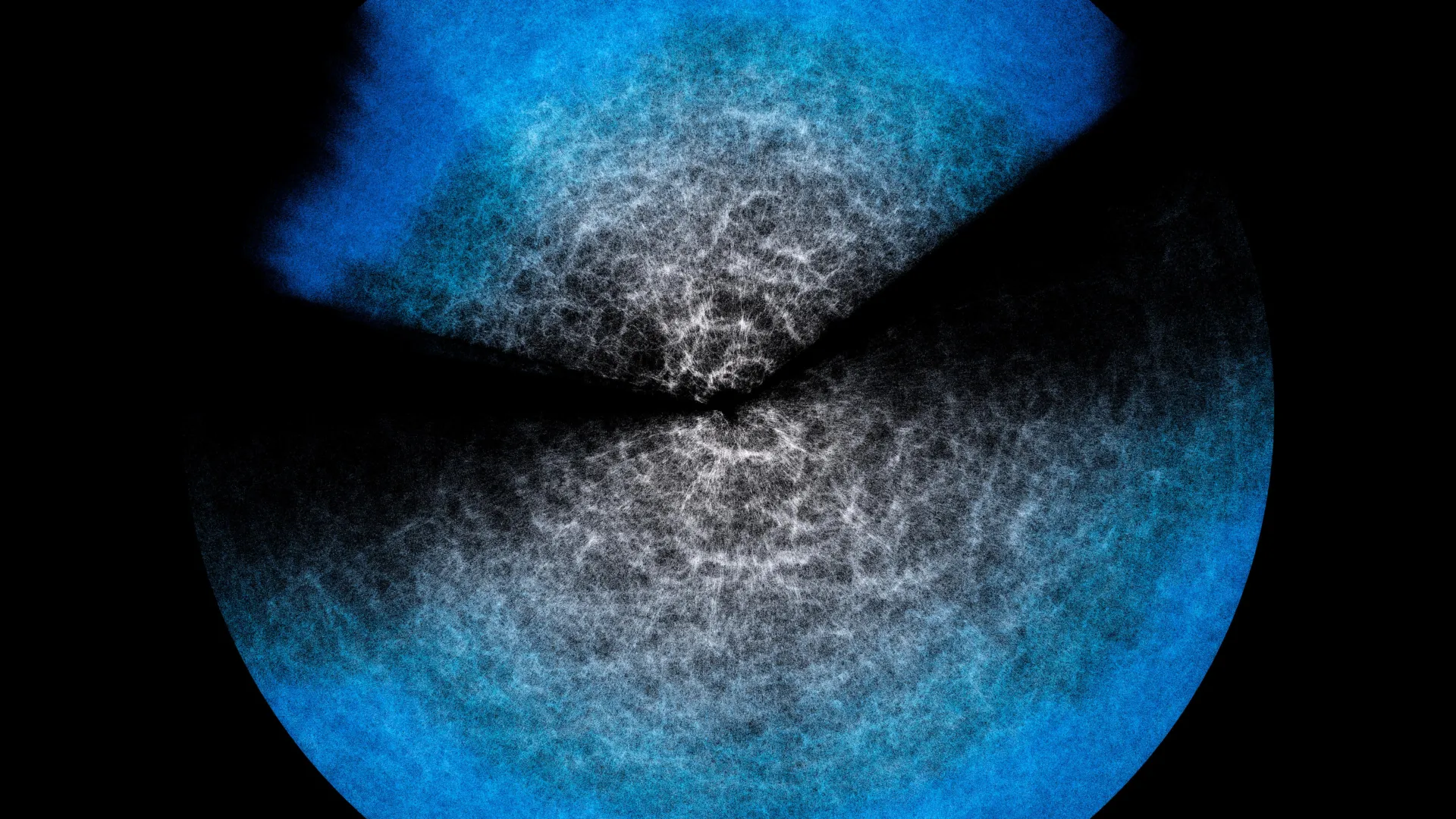

In certain specialized materials, this ordinarily predictable electron flow can undergo a dramatic transformation. Instead of a steady stream, the electrons can spontaneously organize themselves, locking into rigid, highly ordered, crystal-like patterns. This profound shift signifies a fundamental change in the material’s state of matter. When electrons solidify into these tightly packed arrangements, the material ceases to be a conductor of electricity, effectively transitioning from a metallic state to that of an insulator. This seemingly counterintuitive phenomenon, where electricity is shut off by the very particles that create it, is a treasure trove of insight for scientists striving to understand the intricate web of electron interactions. The implications of this research are vast, paving the way for revolutionary advancements in fields as diverse as quantum computing, the development of high-performance superconductors crucial for efficient energy transmission and advanced medical imaging techniques like MRI, the creation of more energy-efficient and innovative lighting systems, and the construction of atomic clocks of unprecedented precision.

A groundbreaking discovery has emerged from the laboratories of Florida State University, where a dedicated team of physicists, comprising National High Magnetic Field Laboratory Dirac Postdoctoral Fellow Aman Kumar, Associate Professor Hitesh Changlani, and Assistant Professor Cyprian Lewandowski, has meticulously identified the precise conditions necessary for the formation of a particularly intriguing type of electron crystal. This novel quantum state exhibits a remarkable duality: the electrons arrange themselves into a solid, ordered lattice, yet paradoxically retain the capacity to shift into a more fluid, mobile form. This hybrid phase, a fascinating blend of order and mobility, has been christened a generalized Wigner crystal. The team’s seminal findings, meticulously documented and analyzed, have been published in the esteemed scientific journal npj Quantum Materials, a prestigious publication within the Nature portfolio.

The Genesis of Electron Crystals: A Deeper Understanding

The concept of electrons solidifying into crystalline structures, known as Wigner crystals, is not entirely new to the scientific community. This theoretical framework was first posited by Eugene Wigner in 1934, envisioning a scenario where the repulsive forces between electrons in a sufficiently dilute system could overcome their kinetic energy, leading to their arrangement in a stable, ordered lattice. In more recent years, experimental evidence has begun to corroborate these theoretical predictions, with researchers detecting the physical manifestations of these electron crystals. However, a complete and comprehensive understanding of the intricate mechanisms governing their formation, particularly when considering the added complexity of quantum mechanical effects, had remained an elusive goal.

The research team at Florida State University has now successfully navigated this complex terrain. "In our study, we determined which ‘quantum knobs’ to turn to trigger this phase transition and achieve a generalized Wigner crystal," explained Professor Changlani. He elaborated on the significance of this achievement, highlighting how their approach, utilizing a 2D moiré system, unlocks the potential for a diverse array of crystalline shapes, including stripes and honeycomb arrangements. This stands in stark contrast to the traditional Wigner crystals, which are inherently limited to a triangular lattice structure. This ability to engineer different crystalline forms opens up a vast new landscape for scientific exploration and technological application.

To unravel these intricate conditions, the physicists leveraged the formidable computational resources available at FSU’s Research Computing Center, a vital academic service unit managed by Information Technology Services. Furthermore, their research was significantly enabled by the National Science Foundation’s ACCESS program, which provides access to advanced computing and data resources under the umbrella of the Office of Advanced Cyberinfrastructure. The team employed a sophisticated arsenal of computational methodologies, including exact diagonalization, density matrix renormalization group (DMRG), and Monte Carlo simulations. These powerful techniques allowed them to meticulously probe and analyze the behavior of electrons under a wide spectrum of simulated conditions, providing invaluable insights into the quantum mechanics at play.

Navigating the Labyrinth of Quantum Data

The sheer volume of information generated by quantum mechanical calculations is staggering. According to the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics, each electron is associated with two distinct pieces of information. When hundreds or even thousands of these particles engage in complex interactions, the total dataset escalates exponentially, presenting a formidable challenge for analysis. To overcome this hurdle, the researchers developed and employed sophisticated algorithms designed to compress and organize this overwhelming deluge of data. This intricate process transformed the raw quantum information into manageable networks that could be effectively examined and interpreted by the scientific team.

"We’re able to mimic experimental findings via our theoretical understanding of the state of matter," stated Dr. Kumar, highlighting the crucial link between theoretical prediction and experimental validation. He further detailed their rigorous computational approach: "We conduct precise theoretical calculations using state-of-the-art tensor network calculations and exact diagonalization, a powerful numerical technique used in physics to collect details about a quantum Hamiltonian, which represents the total quantum energy in a system." He emphasized the profound utility of this method: "Through this, we can provide a picture for how the crystal states came about and why they’re favored in comparison to other energetically competitive states." This meticulous theoretical work provides a crucial framework for understanding the observed phenomena.

Introducing the Quantum Pinball Phase: A Novel State of Matter

During their intensive investigation of the generalized Wigner crystal, the research team made an even more astonishing discovery, unearthing a previously unidentified state of matter. This newly characterized phase exhibits a truly remarkable characteristic: electrons simultaneously display both insulating and conducting behaviors. Within this peculiar state, a segment of the electrons remains rigidly anchored in place, locked within the crystalline lattice. Concurrently, another population of electrons breaks free from this confinement, embarking on a journey of free movement throughout the material. The motion of these mobile electrons has been likened to that of a pinball, ricocheting erratically between stationary obstacles.

"This pinball phase is a very exciting phase of matter that we observed while researching the generalized Wigner crystal," enthused Dr. Lewandowski. He elaborated on the profound implications of this observation: "Some electrons want to freeze and others want to float around, which means that some are insulating and some are conducting electricity. This is the first time this unique quantum mechanical effect has been observed and reported for the electron density we studied in our work." This groundbreaking discovery challenges conventional understandings of electron behavior and opens up new avenues for research into exotic states of matter.

The Far-Reaching Significance of These Discoveries

The ramifications of these discoveries extend far beyond the confines of theoretical physics, significantly enhancing humanity’s capacity to comprehend and manipulate the behavior of matter at its most fundamental, quantum level.

"What causes something to be insulating, conducting or magnetic? Can we transmute something into a different state?" posed Dr. Lewandowski, articulating the fundamental questions that drive condensed matter physics research. He continued, "We’re looking to predict where certain phases of matter exist and how one state can transition to another — when you think of turning a liquid into gas, you picture turning up a heat knob to get water to boil into steam. Here, it turns out there are other quantum knobs we can play with to manipulate states of matter, which can lead to impressive advances in experimental research." The analogy of "quantum knobs" effectively conveys the idea that by precisely controlling specific quantum parameters, scientists can induce phase transitions, akin to adjusting temperature to change the state of water.

By judiciously adjusting these "quantum knobs," which correspond to specific energy scales within the material, researchers gain the ability to transition electrons between solid and liquid phases. A profound understanding of Wigner crystals and their associated emergent states holds the potential to profoundly shape the future trajectory of quantum technologies. This includes the burgeoning field of quantum computing, which promises to solve problems currently intractable for even the most powerful classical supercomputers, and spintronics. Spintronics, a rapidly evolving frontier in condensed-matter physics, endeavors to harness the intrinsic spin of electrons, in addition to their charge, to create faster, more energy-efficient, and cost-effective nano-electronic devices.

The research team is committed to further unraveling the complex interplay of electron cooperation and mutual influence within intricate quantum systems. Their ultimate aspiration is to address fundamental scientific questions that could catalyze transformative innovations across a spectrum of advanced technologies, including quantum computing, superconductivity, and precision atomic measurements. This ongoing pursuit promises to unlock new frontiers in scientific understanding and technological capability.