The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), a beacon of scientific endeavor and human exploration, finds itself once again embroiled in a deeply unsettling budgetary crisis, exacerbated by recent governmental disruptions. The government shutdown late last year not only stalled crucial legislative processes but also cast a long shadow over the agency’s operational future. At the heart of the contention lies a stark divergence in vision: while the Trump administration has proposed a drastic, nearly 50 percent reduction in NASA’s science budget—a move critics have decried as an “extinction-level” event for American space exploration and scientific research—Congress appears inclined to maintain the agency’s funding largely intact, safeguarding a multitude of vital missions.

This budgetary standoff places NASA in a precarious position, its fate hanging in the balance between executive austerity and legislative preservation. The proposed cuts by the White House are not merely abstract figures; they threaten to dismantle ongoing projects and future initiatives that are fundamental to our understanding of Earth, our solar system, and the cosmos beyond. Missions ranging from climate monitoring satellites to deep-space probes designed to unlock the secrets of distant planets and moons could find themselves on the chopping block, potentially halting decades of progress and squandering significant investments in scientific capital and human ingenuity. The short-term resolution passed on November 12, extending government funding only until January 31, merely postpones the inevitable confrontation, leaving NASA in a perpetual state of uncertainty.

Adding another layer to this complex situation is the agency’s recently sworn-in administrator, Jared Isaacman. A former SpaceX space tourist and a prominent figure in the private space industry, Isaacman has yet to offer a definitive public statement directly addressing the library closure. However, his previously articulated alignment with the Trump administration’s emphasis on private industry-led space exploration signals a potential shift in NASA’s strategic direction. This approach, while championed by some as a path to innovation and efficiency, raises concerns among others about the prioritization of commercial ventures over fundamental scientific research and public-funded exploratory missions, particularly when it comes to critical Earth science and climate research initiatives.

Amidst this prevailing atmosphere of financial ambiguity and strategic reevaluation, the Trump administration has embarked on a controversial campaign to “gut” entire buildings at NASA’s iconic Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC). Located in Greenbelt, Maryland, GSFC is not merely a collection of offices; it is a historical and intellectual powerhouse, having played an indispensable role in the development and operation of some of humanity’s most groundbreaking scientific instruments. This includes the revolutionary James Webb Space Telescope, the venerable Hubble Space Telescope, and a myriad of other critical missions focused on Earth science, astrophysics, planetary science, and heliophysics. The center is a hub for research, engineering, and mission management, making the systematic emptying of its facilities a profound concern for the scientific community.

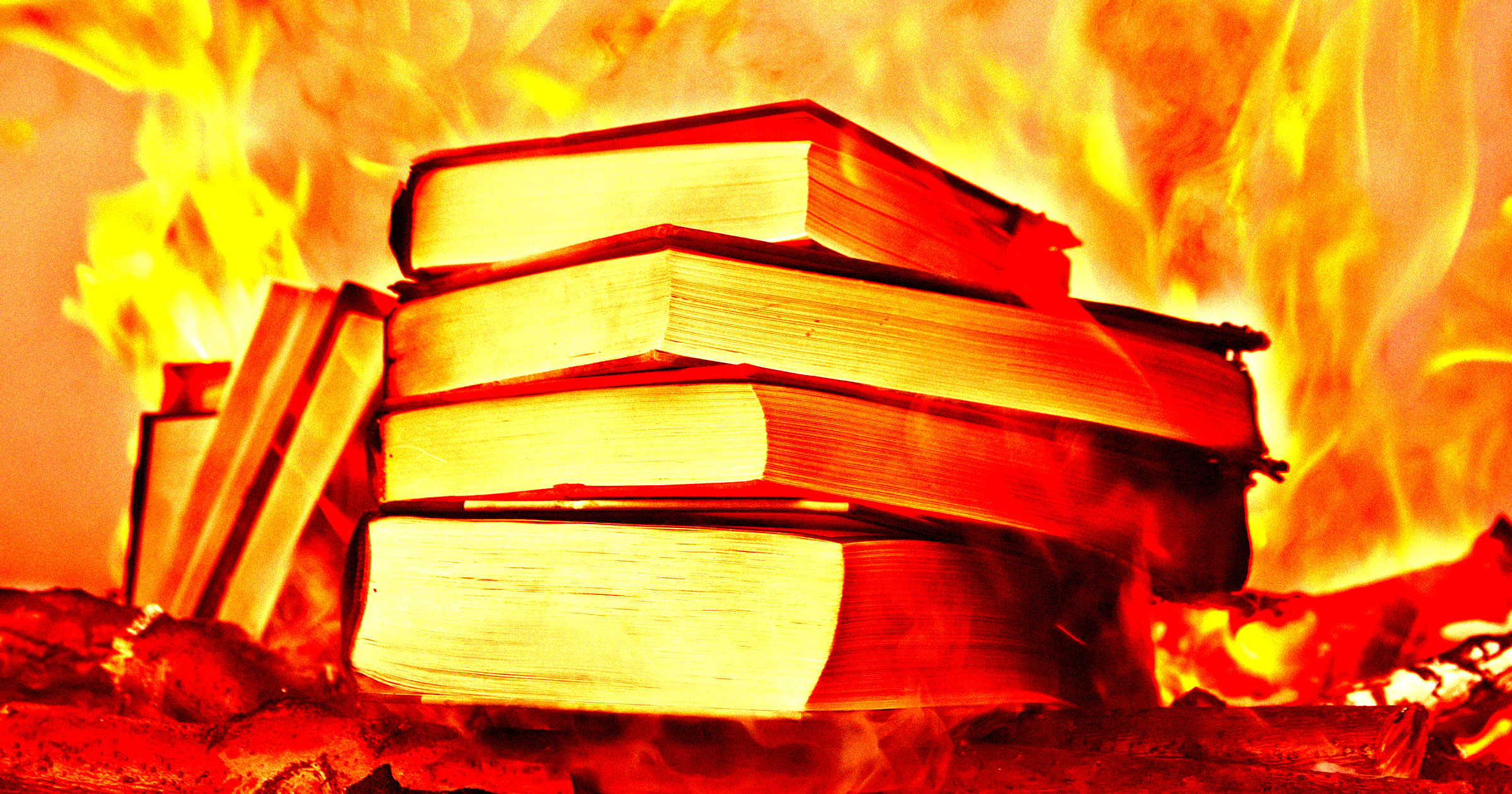

The most recent and perhaps most alarming development emerged this week: the administration’s decision to shut down the GSFC library, NASA’s largest repository of knowledge. More than just a quiet reading room, this library is a treasure trove of scientific and historical documentation, housing an unparalleled collection of books, technical reports, journals, and archival materials that chronicle over half a century of space exploration, dating back to the Apollo era. The news carried a particularly chilling detail: an “undetermined number” of these invaluable artifacts are reportedly slated for destruction, a prospect that has ignited outrage and dismay among scientists, historians, and policymakers alike.

The gravity of this situation is underscored by reports from The New York Times, which highlighted that a significant portion of these invaluable materials has never been digitized or made available through other means. This means that if these physical records are destroyed, the knowledge they contain could be lost forever, severing crucial links to past research, methodologies, and even failures—lessons that are vital for future endeavors. While a NASA spokesperson initially told the newspaper that the agency would conduct a 60-day review to determine what to keep and what to discard, the very notion of “tossing away” any part of this unique scientific and historical archive paints a stark picture of an agency seemingly in crisis, potentially discarding its own institutional memory.

Following the initial uproar stirred by The New York Times report, NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman took to social media platform X to push back against the claims. He asserted that “The [NYT] story does not fully reflect the context NASA shared,” and emphatically stated, “At no point is NASA ‘tossing out’ important scientific or historical materials, and that framing has led to several other misleading headlines.” However, this statement appears to directly contradict earlier reporting. The NYT specifically quoted NASA spokesman Jacob Richmond, who reportedly stated that “the agency would review the library holdings over the next 60 days and some material would be stored in a government warehouse while the rest would be tossed away.” This discrepancy raises serious questions about the transparency and consistency of information being provided by the agency.

Further complicating the narrative, NASA press secretary Bethany Stevens characterized the initiative not as a “closure” but as a “consolidation.” She explained that the Trump administration intends to close 13 buildings and more than 100 labs across the vast GSFC campus by March. Stevens claimed these actions are part of a broader “master plan reorganization effort” that was initially devised in 2022, several years prior to Donald Trump’s presidency. This suggests that the current administration is accelerating or reinterpreting a pre-existing plan. Nevertheless, the scale of these closures is immense, and it follows a pattern: according to The New York Times, seven other NASA libraries have already been shuttered since 2022, with three of those closures occurring just last year in 2025.

The concerns extend far beyond the invaluable paper archives. Last November, NASA staffers themselves raised alarms about word that over a dozen buildings on the GSFC campus were being emptied with little to no prior notice. Their warnings highlighted a dire threat: not just books and documents, but highly specialized, irreplaceable scientific equipment was at imminent risk of being discarded like common trash. This equipment, often custom-built for specific research purposes, represents monumental investments in time, expertise, and taxpayer money. Its loss would not only impede ongoing research but also incur exorbitant costs for replacement, if replacement is even possible, setting back scientific programs for years and potentially costing more than the perceived savings from the “consolidation.”

The Trump administration’s handling of this situation has drawn fierce condemnation from lawmakers. Senator Chris Van Hollen (D-MA) voiced his outrage to The New York Times, stating, “The Trump Administration has spent the last year attacking NASA Goddard and its workforce and threatening our efforts to explore space, deepen our understanding of Earth, and spur technological advancements that make our economy stronger and nation safer.” He added, “These reports of closures at Goddard are deeply concerning — I will continue to push back on any actions that impact Goddard’s critical mission.” Such legislative pushback underscores the bipartisan concern for NASA’s stability and its foundational role in American scientific leadership and innovation.

The GSFC library, with its extensive collection, serves as a vital repository of institutional memory, housing critical documentation about our efforts to study the cosmos, from the early days of rocketry to the ambitious Apollo missions and beyond. This historical record provides context, prevents the repetition of past mistakes, and informs future research directions. Critics of the moves to gut the campus and close its library argue that abandoning these documents would be an act of profound recklessness. Planetary scientist Dave Williams, who opted for an early retirement from NASA last year in response to the agency’s shifting priorities, powerfully articulated this sentiment to the NYT: “It’s not like we’re so much smarter now than we were in the past. It’s the same people, and they make the same kind of human errors. If you lose that history, you are going to make the same mistakes again.” This speaks to the invaluable, often underestimated, role of historical archives in scientific progress.

The unfolding events at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center represent a critical juncture for the agency and for the future of American scientific research and space exploration. The interplay of budgetary pressures, administrative decisions, and the potential loss of invaluable historical and scientific resources paints a sobering picture. As the debate continues over whether these actions constitute necessary “consolidation” or destructive “closures,” the long-term implications for NASA’s capabilities, its institutional memory, and its global standing in the scientific community remain deeply uncertain. The scientific community, lawmakers, and the public await clearer answers and a commitment to preserving the heritage and future of humanity’s reach for the stars.

Updated with additional context from NASA.