A decade ago, accidentally landing on a "parked" domain – typically an expired, dormant, or misspelled version of a popular website – presented a minor risk. Researchers found in 2014 that less than five percent of such redirects led to malicious sites. However, a new, extensive study by security firm Infoblox reveals a dramatic and alarming reversal of this trend: visiting these parked domains now overwhelmingly leads to malicious content, scams, and malware. This significant shift has transformed a previously low-risk internet navigation method into a substantial cybersecurity threat, particularly for users who rely on direct navigation.

The concept of direct navigation, where users manually type a domain name into their web browser, has long been a fundamental aspect of internet usage. However, the findings from Infoblox indicate that this seemingly straightforward action has become fraught with peril. When users encounter expired domain names or make common typographical errors when attempting to visit legitimate websites (a practice known as typosquatting), they often land on placeholder pages managed by domain parking companies. These companies aim to monetize the traffic by displaying links to third-party websites that have paid for advertising space.

Historically, these parking pages served as relatively benign gateways, offering a limited chance of encountering malicious content. The 2014 USENIX Security conference paper highlighted that even without user interaction, the probability of being redirected to a harmful site was minimal. This contrasted sharply with the current landscape. Infoblox’s recent experiments, conducted over several months, paint a grim picture: the vast majority of parked domains are now actively configured to deliver malicious payloads.

Infoblox researchers detailed their findings in a white paper published today, stating, "In large scale experiments, we found that over 90% of the time, visitors to a parked domain would be directed to illegal content, scams, scareware and anti-virus software subscriptions, or malware, as the ‘click’ was sold from the parking company to advertisers, who often resold that traffic to yet another party." This indicates a sophisticated, multi-layered ecosystem where traffic from unsuspecting users is systematically exploited.

The security firm observed a peculiar behavior related to how users access these parked domains. If a visitor accesses a parked website using a Virtual Private Network (VPN) or from a non-residential IP address, the domain typically displays a harmless parking page. However, users connecting from residential IP addresses, especially on mobile devices or desktop computers, are immediately redirected to deceptive content. This suggests that attackers are tailoring their attacks to exploit the perceived trust associated with standard home internet connections.

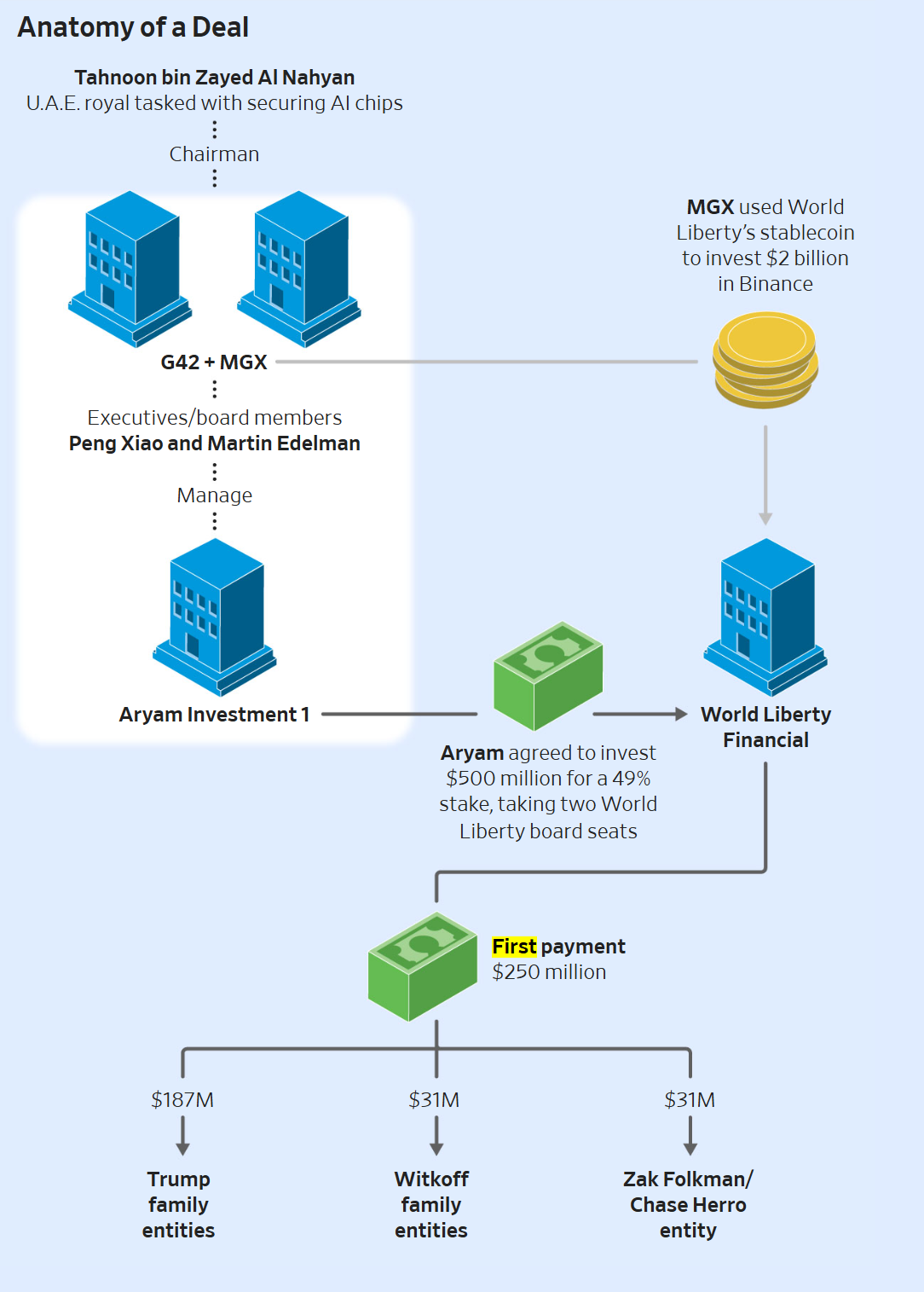

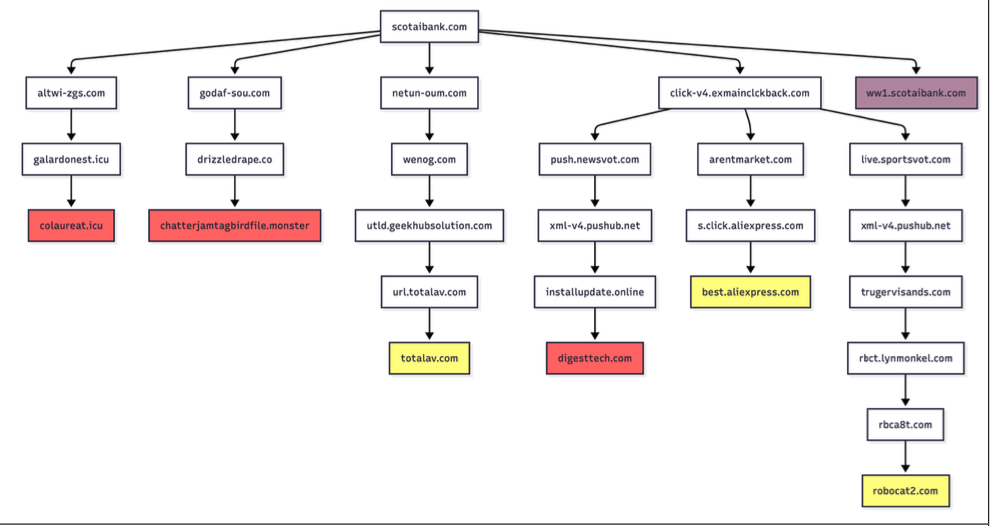

A striking example of this exploitation involves the domain "scotaibank[.]com," a deliberate misspelling of "Scotiabank.com." Infoblox discovered that the entity controlling this domain also manages a portfolio of nearly 3,000 similar lookalike domains. Among these is "gmai[.]com," which has been configured with its own mail server. This means that any email sent to a Gmail user that accidentally omits the ‘l’ from "gmail.com" is not lost but is instead rerouted directly to these scammers. The report further notes that this specific domain has been implicated in numerous recent Business Email Compromise (BEC) campaigns, often using lures related to failed payments and attaching trojan malware.

Infoblox identified "torresdns[.]com" as the common DNS server used by the owner of these typosquatting domains. This individual or entity has established a wide net, targeting dozens of top internet destinations. The list includes prominent platforms like Craigslist, YouTube, Google, Wikipedia, Netflix, TripAdvisor, Yahoo, eBay, and Microsoft. A de-fanged version of these typosquatting domains, where dots are replaced by commas for safety, is available for review.

David Brunsdon, a threat researcher at Infoblox, elaborated on the redirection process. He explained that parked pages often initiate a chain of redirects. During this process, the visitor’s system is meticulously profiled using techniques such as IP geolocation, device fingerprinting, and cookies. This profiling helps determine the most opportune redirect destination. "It was often a chain of redirects – one or two domains outside the parking company – before threat arrives," Brunsdon stated. "Each time in the handoff the device is profiled again and again, before being passed off to a malicious domain or else a decoy page like Amazon.com or Alibaba.com if they decide it’s not worth targeting." This multi-stage profiling allows attackers to maximize their chances of delivering a successful exploit or scam.

Brunsdon also commented on the disconnect between the claims of domain parking services and the reality of their operations. While parking companies assert that their search results are relevant to the parked domains, Infoblox’s testing revealed that almost none of the displayed content was related to the lookalike domain names they examined. This further underscores the deceptive nature of these parked pages.

Another threat actor identified by Infoblox operates "domaincntrol[.]com," a domain that differs from GoDaddy’s name servers by a single character. This actor has long leveraged typos in DNS configurations for malicious purposes. However, Infoblox recently observed a new tactic: malicious redirects from this domain are now only triggered when queries originate from Cloudflare’s DNS resolvers (1.1.1.1). All other visitors are presented with a page that refuses to load, suggesting a highly targeted and sophisticated attack strategy.

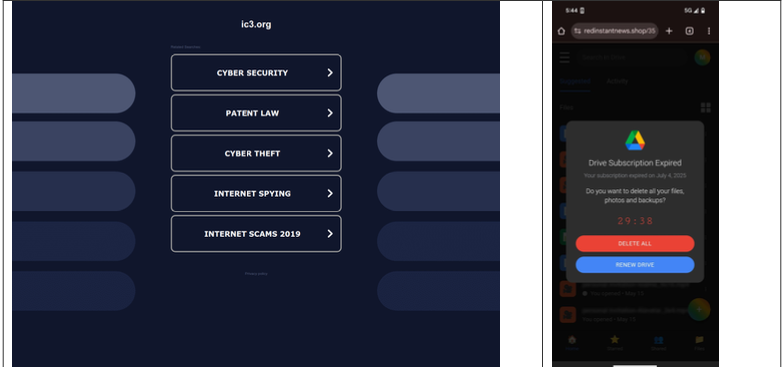

The pervasiveness of this threat extends even to government domains. Researchers discovered that variations of well-known government domains are being targeted by malicious ad networks. In one instance, an Infoblox researcher attempting to report a crime to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) inadvertently visited "ic3[.]org" instead of the correct "ic3[.]gov." Their device was quickly redirected to a fraudulent "Drive Subscription Expired" page. The researchers noted that while they encountered a scam, they could have just as easily been exposed to information-stealing malware or trojans, highlighting the unpredictable nature of these malicious redirects.

Crucially, the Infoblox report emphasizes that the malicious activity observed is not attributed to any single, known entity. The domain parking and advertising platforms mentioned in the study were not directly implicated in the documented malvertising campaigns. However, the report points out that despite claims of working only with reputable advertisers, the traffic directed to these parked domains was frequently sold to affiliate networks. These networks, in turn, often resold the traffic, creating a situation where the ultimate advertiser had no direct relationship with the original domain parking company. This obfuscation makes attribution and remediation exceptionally difficult.

Infoblox also drew attention to recent policy changes by Google that may have inadvertently exacerbated the risks associated with direct search abuse. Previously, Google AdSense ads were permitted on parked pages by default. However, in early 2025, Google implemented a default setting that requires advertisers to opt-in to displaying their ads on parked domains. This change, while intended to curb abuse, might have created new avenues for exploitation as malicious actors adapt to the evolving advertising landscape. The researchers concluded that the ecosystem of parked domains has transformed from a minor nuisance into a significant and pervasive threat vector, demanding increased vigilance from internet users and proactive measures from cybersecurity stakeholders.