A decade ago, accidentally landing on a parked domain, often a placeholder page for expired or misspelled website addresses, presented a relatively low risk of encountering malicious content. In 2014, research indicated that parked domains redirected users to malicious sites less than five percent of the time, irrespective of whether visitors clicked on any links. However, recent extensive experiments conducted by the cybersecurity firm Infoblox have dramatically reversed this trend, finding that malicious content is now the overwhelming norm for parked websites.

Infoblox’s findings, detailed in a comprehensive paper, demonstrate that in large-scale experiments, over 90% of the time, visitors to parked domains were directed to illegal content, scams, scareware, deceptive antivirus software subscriptions, or outright malware. This alarming shift is attributed to the monetization model of domain parking: the "click" from a parked page is sold by the parking company to advertisers, who in turn often resell this traffic to further parties down the line. This multi-layered reselling creates an opaque ecosystem where the ultimate destination of user traffic can be far removed from the initial parking service.

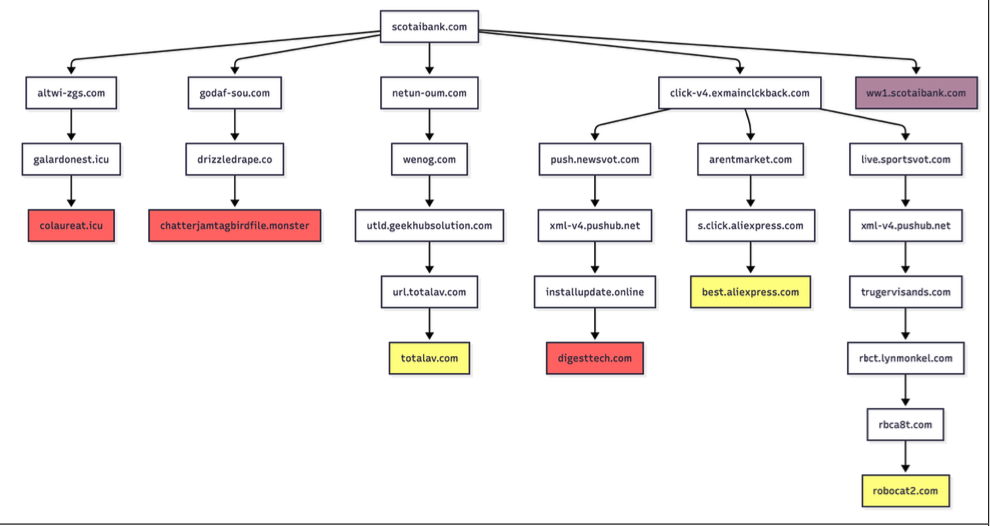

The study highlights a particularly concerning tactic: malicious actors are actively registering and configuring domain names that are slight misspellings of popular and trusted websites, a practice known as "typosquatting." For instance, customers of Scotiabank who mistakenly type "scotaibank.com" instead of the correct "scotiabank.com" may find themselves redirected to deceptive content. The nature of this redirection, Infoblox discovered, is often dependent on the visitor’s location and network. While users accessing these misspelled domains via a Virtual Private Network (VPN) or non-residential internet addresses might still encounter a benign parking page, those using residential IP addresses, common for home internet users, are immediately directed to sites peddling scams, malware, or other unwanted content. This redirection occurs simply by visiting the misspelled domain, whether on a mobile device or a desktop computer.

One striking example of this sophisticated typosquatting operation involves a domain owner who has amassed a portfolio of nearly 3,000 lookalike domains. This individual or entity controls domains such as "gmai.com," which is not merely a parked page but is configured with its own mail server capable of accepting incoming emails. This means that if a user accidentally omits the "l" from "gmail.com" when sending an email, their message doesn’t bounce back but is instead delivered directly to these scammers. The report further reveals that this specific domain has been instrumental in numerous recent business email compromise (BEC) campaigns, often employing lures that suggest a failed payment and include trojan malware attachments.

The common DNS server "torresdns.com" has been identified as the infrastructure supporting this prolific typosquatting operation. This operator has established lookalike domains targeting dozens of leading internet destinations, including household names like Craigslist, YouTube, Google, Wikipedia, Netflix, TripAdvisor, Yahoo, eBay, and Microsoft. A de-fanged list of these typosquatting domains, where dots have been replaced with commas to prevent accidental navigation, is available for public reference.

David Brunsdon, a threat researcher at Infoblox, explained the intricate redirection chains employed by these malicious parked pages. Visitors are often sent through one or two intermediary domains outside of the parking company’s direct control before reaching the final threat. During each handoff in this chain, the visitor’s device is profiled repeatedly using techniques such as IP geolocation, device fingerprinting, and cookies. This profiling helps the attackers determine the most opportune redirection. If the system deems a visitor not worth targeting—perhaps due to their location or device characteristics—they might be redirected to a decoy page mimicking legitimate sites like Amazon.com or Alibaba.com, a tactic designed to further obfuscate the malicious intent. Brunsdon noted that despite claims by domain parking services to provide relevant search results, the content displayed on the tested parked pages bore little relation to the lookalike domain names they were associated with.

Another identified threat actor, operating under the domain "domaincntrol.com"—a domain that differs from GoDaddy’s legitimate name servers by a single character—has a history of exploiting typos in DNS configurations to direct users to malicious websites. Infoblox’s recent observations indicate a new layer of sophistication: this malicious redirect now appears to be conditional. It primarily occurs when a query for the misconfigured domain originates from a visitor using Cloudflare’s DNS resolvers (1.1.1.1). For all other visitors, the site simply refuses to load, a behavior likely designed to evade detection by security researchers or specific network monitoring tools.

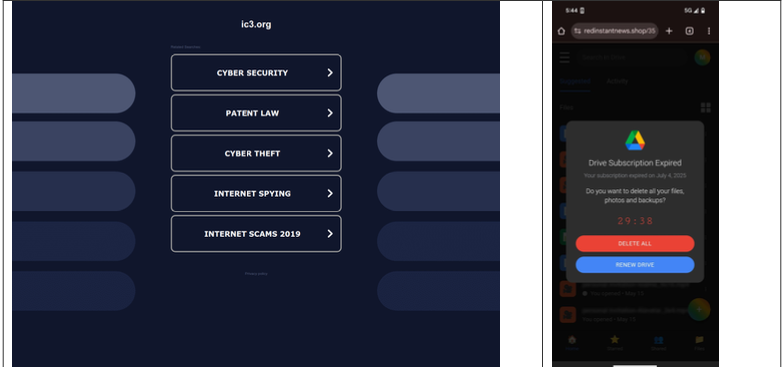

The Infoblox report also underscores that even variations of well-known government domains are falling prey to these malicious ad networks. In one alarming instance, a researcher attempting to report a crime to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) inadvertently navigated to "ic3.org" instead of the correct ".gov" domain. Their phone was swiftly redirected to a fraudulent "Drive Subscription Expired" page. While the researcher was fortunate to encounter only a scam, the report emphasizes that users could just as easily be exposed to information-stealing malware or trojans through such misdirected visits.

Significantly, the malicious activity documented by Infoblox is not attributed to any single known entity. The domain parking or advertising platforms named in the study were not directly implicated in the malvertising campaigns observed. However, the report concludes that while parking companies often claim to partner only with reputable advertisers, the traffic directed to these domains is frequently sold to affiliate networks. These networks, in turn, often resell the traffic multiple times, creating a situation where the ultimate advertiser may have no direct business relationship with the original domain parking company, thus diffusing accountability.

Infoblox also pointed out that recent policy changes by Google may have inadvertently amplified the risks associated with direct search abuse. Brunsdon mentioned that Google AdSense previously allowed ads to be placed on parked pages by default. However, in early 2025, Google implemented a default setting that requires advertisers to actively opt-in to displaying their ads on parked domains, rather than opting out. While seemingly a security enhancement, this shift could lead to a scenario where advertisers who are less security-conscious might overlook this setting, potentially increasing the flow of malicious advertisements through these channels. The report emphasizes that the onus is now on the advertiser to ensure their ads are not inadvertently contributing to the spread of malware and scams via parked domains. The entire ecosystem of domain parking, typosquatting, and ad reselling presents a complex and evolving threat landscape that demands heightened user vigilance and continued security research.