Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan have achieved a groundbreaking feat in robotics, creating the smallest fully programmable autonomous robots ever developed. These microscopic machines, barely visible to the naked eye, possess the remarkable ability to swim through liquids, perceive their environment, make independent decisions, and operate for extended periods, all while costing a mere penny to produce. This innovation heralds a new era of micro-robotics with profound implications for fields ranging from medicine to advanced manufacturing.

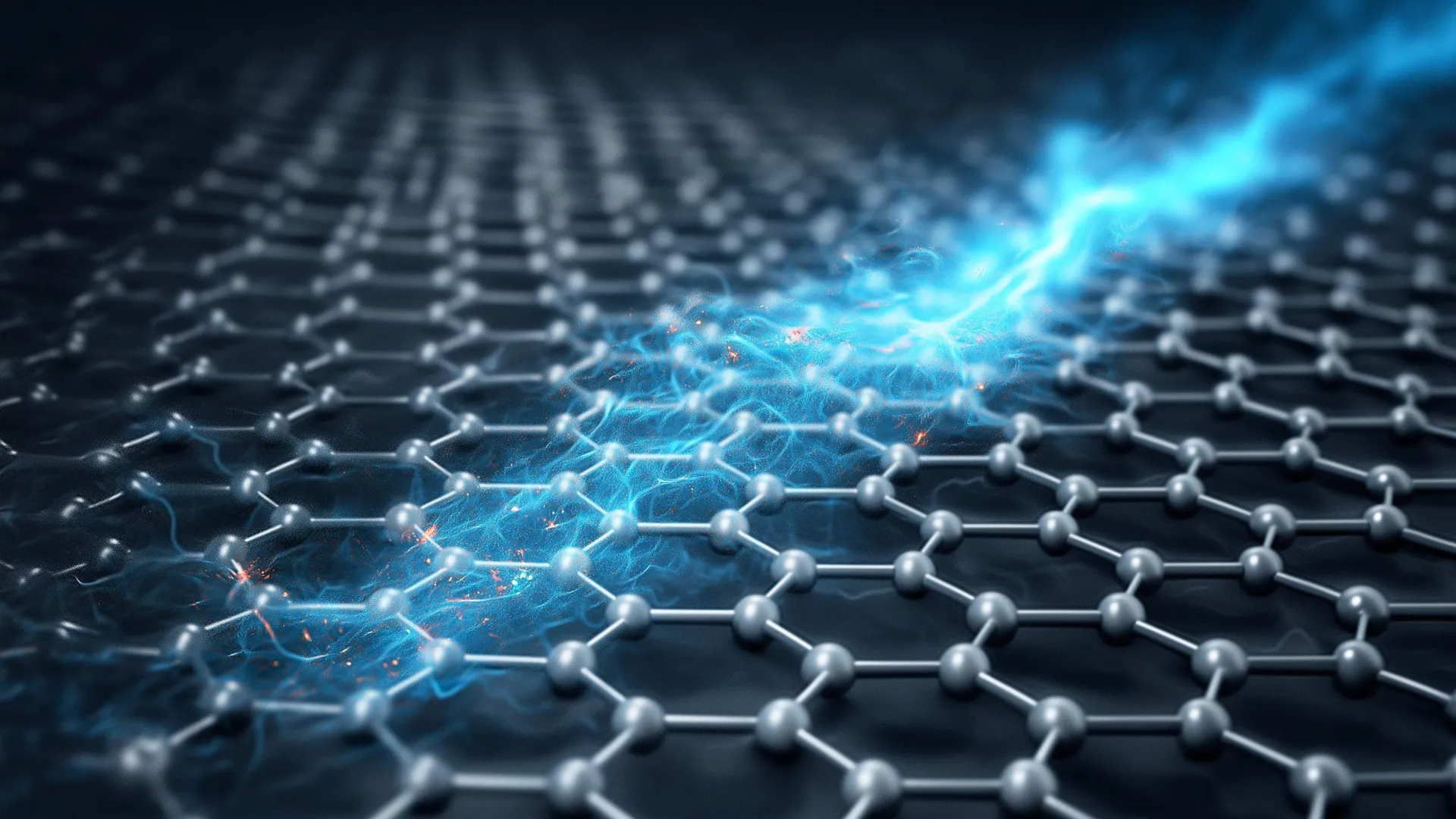

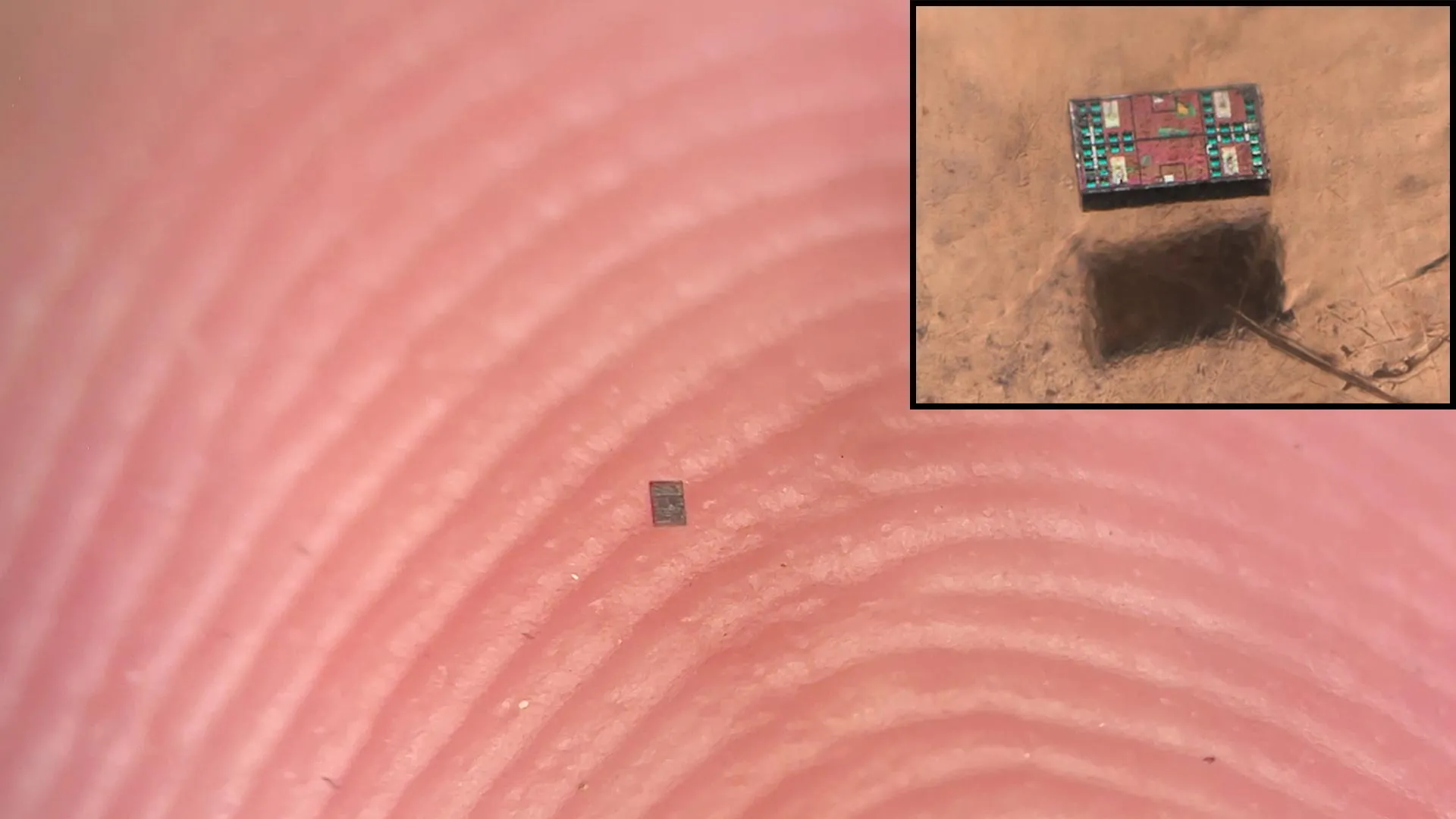

Each of these miniature robots measures approximately 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers, making them significantly smaller than a grain of salt. Their diminutive size places them on par with many living microorganisms, opening up a vast array of potential applications. Imagine these tiny robots navigating the human bloodstream to monitor individual cells, delivering targeted therapies, or assisting surgeons with unprecedented precision. In manufacturing, they could be deployed to assemble intricate devices at scales previously unimaginable, revolutionizing the production of electronics and other high-tech components.

The intelligence and autonomy of these robots are powered by light. Integrated microscopic computers allow them to follow pre-programmed paths, detect subtle changes in their surroundings, such as temperature fluctuations, and dynamically adjust their movement in response. This level of self-sufficiency is a significant departure from previous microscopic machines, which often relied on external controls like wires or magnetic fields. The research, published in leading scientific journals Science Robotics and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), underscores the truly autonomous and programmable nature of these innovations.

"We’ve made autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller," states Marc Miskin, Assistant Professor in Electrical and Systems Engineering at Penn Engineering and the senior author of the research papers. "That opens up an entirely new scale for programmable robots." This dramatic reduction in size is not merely an engineering triumph; it signifies a paradigm shift, allowing for the exploration and manipulation of environments at a cellular and molecular level.

The journey to creating such diminutive robots has been fraught with significant challenges. While electronics have consistently shrunk over decades, robotics has lagged behind. "Independence at sizes below one millimeter has remained an unsolved challenge," explains Miskin. "Building robots that operate independently at sizes below one millimeter is incredibly difficult. The field has essentially been stuck on this problem for 40 years." The fundamental physics governing motion at these microscopic scales are drastically different from those experienced in our everyday world. At everyday scales, forces like gravity and inertia, which depend on an object’s volume, are dominant. However, at the microscopic level, surface-related forces, particularly drag and viscosity, become overwhelmingly powerful, fundamentally altering how movement occurs. "If you’re small enough, pushing on water is like pushing through tar," Miskin elaborates.

These altered physical principles render conventional robotic designs ineffective. Tiny legs or arms, common in larger robots, are prone to breaking easily and are exceedingly difficult to manufacture at such minute dimensions. "Very tiny legs and arms are easy to break. They’re also very hard to build," Miskin notes. To surmount these obstacles, the research team devised a novel propulsion system that works in harmony with the physics of the microscopic world rather than attempting to overcome them.

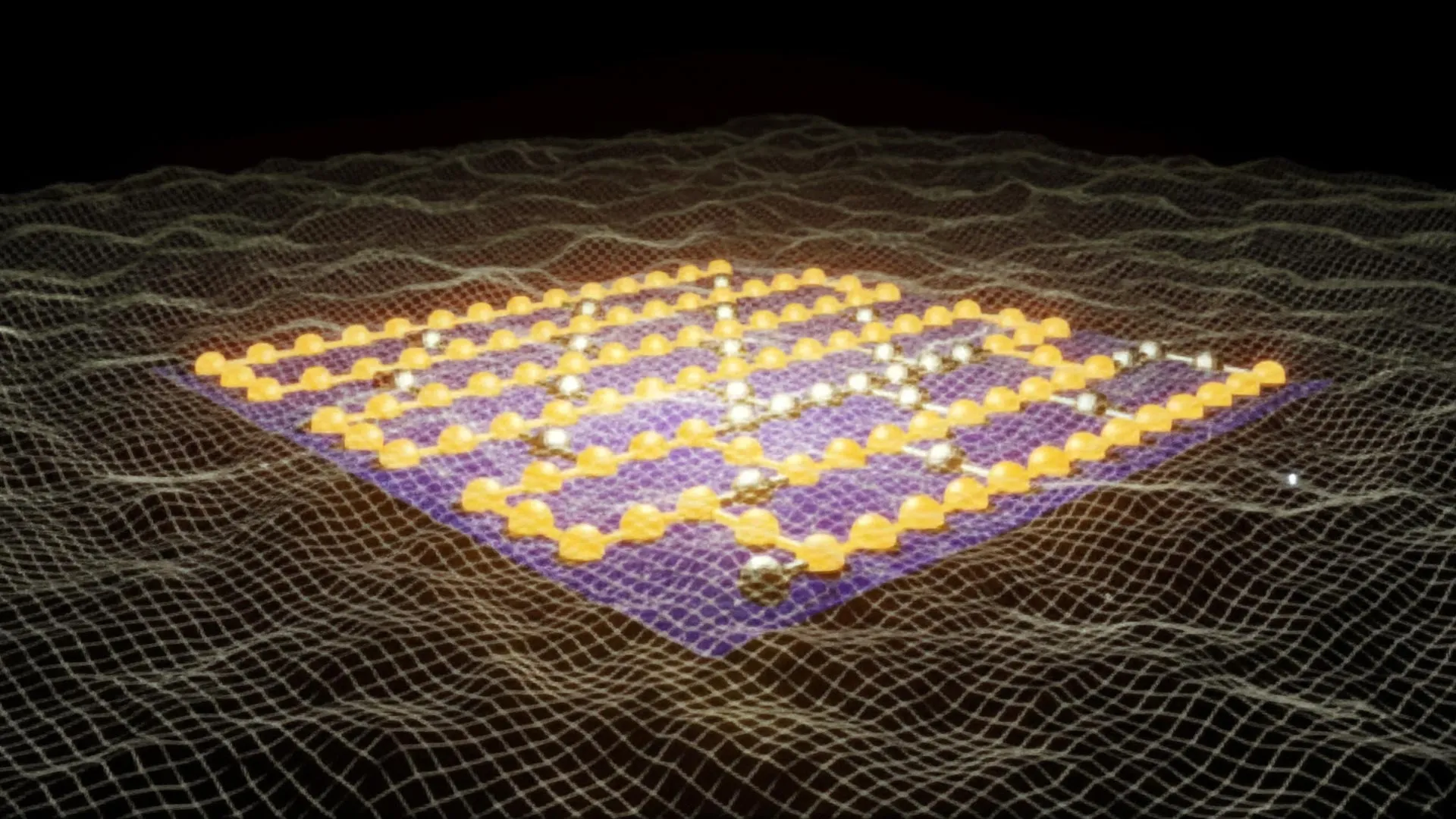

Instead of employing the typical method of pushing water backward, as seen in larger swimmers like fish, these microscopic robots utilize a different strategy. They generate an electrical field that gently interacts with charged particles in the surrounding liquid. As these ions are propelled, they, in turn, drag nearby water molecules, effectively creating a localized current that moves the robot forward. "It’s as if the robot is in a moving river, but the robot is also causing the river to move," describes Miskin. By precisely controlling this electrical field, the robots can navigate complex paths, change direction, and even synchronize their movements in collective formations, reminiscent of schools of fish. Their swimming capabilities allow them to achieve speeds of up to one body length per second.

This light-powered swimming mechanism, devoid of any moving parts, imbues the robots with remarkable durability. Miskin reports that they can be repeatedly transferred between samples using a micropipette without sustaining damage. Powered by light from an LED, these robots can maintain their functionality and swimming capabilities for months on end, a testament to their energy efficiency and robust design.

The development of true autonomy, however, extends beyond mere locomotion. A robot must also possess the ability to perceive its environment, make decisions, and sustain its own power. Integrating all these essential components onto a chip mere fractions of a millimeter across presented a formidable challenge, which was expertly tackled by David Blaauw’s team at the University of Michigan. Blaauw’s laboratory already held the record for fabricating the world’s smallest computer, a feat that made their collaboration with Miskin’s team particularly synergistic. "We saw that Penn Engineering’s propulsion system and our tiny electronic computers were just made for each other," says Blaauw. Despite this apparent synergy, transforming this concept into a functional robot required five years of intensive development.

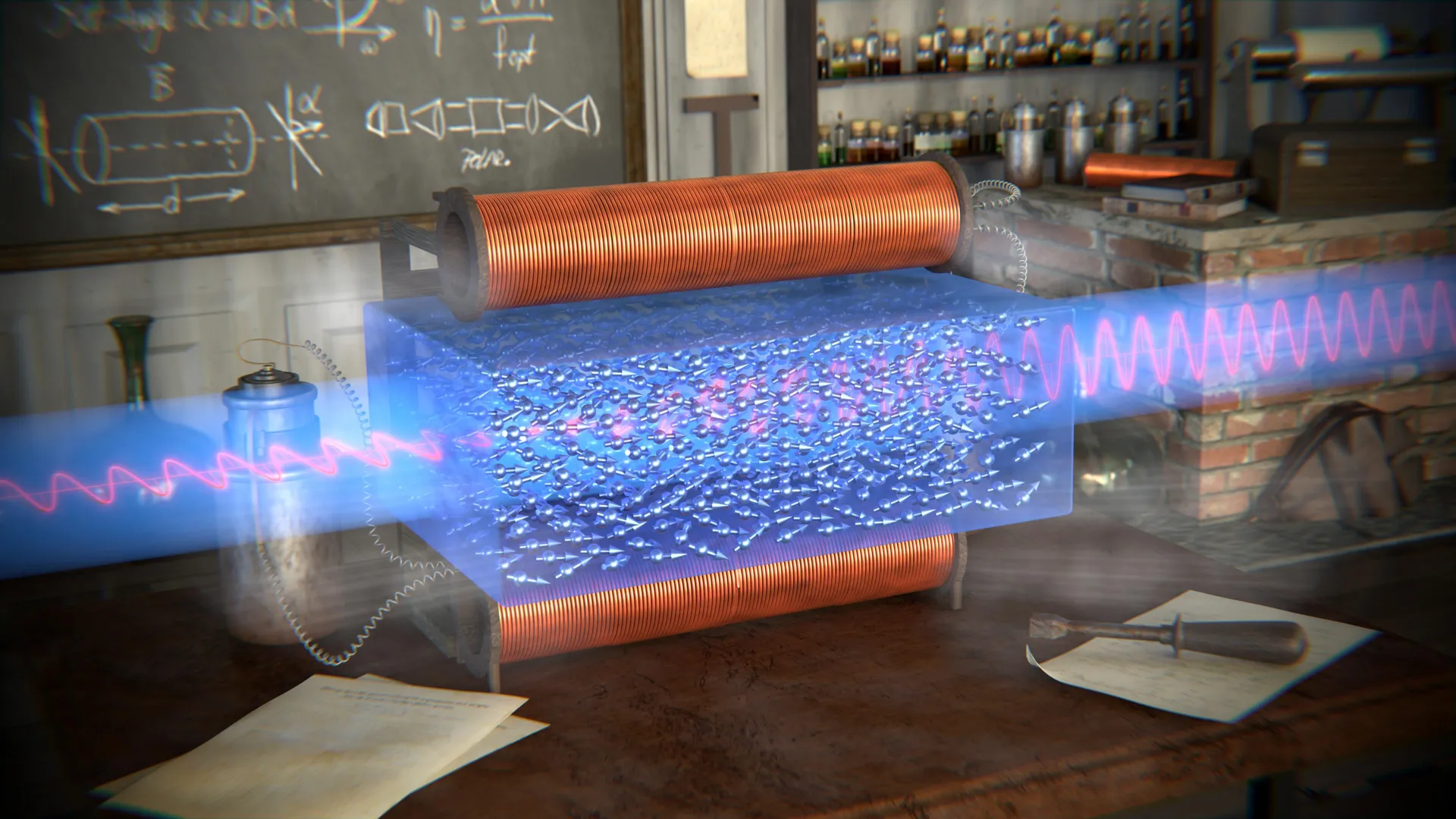

A significant hurdle was the power constraint. "The key challenge for the electronics is that the solar panels are tiny and produce only 75 nanowatts of power. That is over 100,000 times less power than what a smart watch consumes," Blaauw highlights. To overcome this limitation, the team engineered specialized circuits capable of operating at extremely low voltages, thereby reducing power consumption by an astonishing factor of over 1,000.

Space was another critical constraint. The microscopic solar panels occupied a substantial portion of the robot’s surface, leaving minimal room for essential computing hardware. The solution involved a radical redesign of the robot’s software architecture. "We had to totally rethink the computer program instructions," Blaauw explains, "condensing what conventionally would require many instructions for propulsion control into a single, special instruction to shrink the program’s length to fit in the robot’s tiny memory space." This innovative approach to software optimization was crucial for packing the necessary intelligence into such a confined space.

The culmination of these advances has resulted in what the researchers believe to be the first sub-millimeter robot capable of genuine decision-making. To their knowledge, no prior research has successfully integrated a complete computer system, including a processor, memory, and sensors, into a robot of this minuscule size. This integration empowers the robots to perceive their surroundings and act independently, a critical step towards sophisticated micro-robotic applications.

The robots are equipped with electronic temperature sensors that can detect changes as minute as one-third of a degree Celsius. This sensitivity allows them to navigate towards warmer areas or to report temperature values that could serve as indicators of cellular activity, offering a novel method for real-time monitoring of individual cells.

Communicating these collected measurements required an equally ingenious solution. "To report out their temperature measurements, we designed a special computer instruction that encodes a value, such as the measured temperature, in the wiggles of a little dance the robot performs," describes Blaauw. "We then look at this dance through a microscope with a camera and decode from the wiggles what the robots are saying to us. It’s very similar to how honey bees communicate with each other." This bio-inspired communication method allows for efficient data transmission from the microscopic realm.

Remarkably, the same light that powers the robots is also utilized for their programming. Each robot possesses a unique address, enabling researchers to upload distinct instructions to individual units. "This opens up a host of possibilities," Blaauw enthuses, "with each robot potentially performing a different role in a larger, joint task." This programmability allows for sophisticated swarm behaviors and coordinated actions among multiple robots.

The current iteration of these microscopic robots represents just the initial phase of development. Future versions are envisioned to incorporate more advanced programming capabilities, enhanced speed, additional sensor modalities, and the ability to function in more challenging environments. The researchers have intentionally designed the system as a flexible platform, seamlessly integrating a robust propulsion method with cost-effective electronics that can be readily adapted and upgraded over time.

"This is really just the first chapter," concludes Miskin. "We’ve shown that you can put a brain, a sensor and a motor into something almost too small to see, and have it survive and work for months. Once you have that foundation, you can layer on all kinds of intelligence and functionality. It opens the door to a whole new future for robotics at the microscale." This pioneering work lays the foundation for a future where microscopic robots are integral to scientific discovery, medical advancements, and industrial innovation, pushing the boundaries of what is possible at the smallest scales.

The research was a collaborative effort involving the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) School of Engineering and Applied Science, Penn School of Arts & Sciences, and the University of Michigan Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Funding for this groundbreaking project was generously provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF 2221576), the University of Pennsylvania Office of the President, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR FA9550-21-1-0313), the Army Research Office (ARO YIP W911NF-17-S-0002), the Packard Foundation, the Sloan Foundation, and the NSF National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Program (NNCI-2025608), which supports the Singh Center for Nanotechnology, along with contributions from Fujitsu Semiconductors. Key co-authors on the research include Maya M. Lassiter, Kyle Skelil, Lucas C. Hanson, Scott Shrager, William H. Reinhardt, Tarunyaa Sivakumar, and Mark Yim from the University of Pennsylvania, and Dennis Sylvester, Li Xu, and Jungho Lee from the University of Michigan.