The immense computational power and sophisticated outputs of Large Language Models (LLMs) are powered by billions, even trillions, of "parameters." These parameters are the fundamental building blocks that enable LLMs to understand, generate, and manipulate human language with remarkable fluency. At their core, parameters are akin to the adjustable dials and levers within a complex machine, dictating how the model processes information and produces results. Understanding what these parameters are, how they are determined, and their different roles is key to demystifying the inner workings of these revolutionary AI systems.

The concept of parameters in LLMs can be traced back to basic mathematical and programming principles. In algebra, variables like ‘a’ and ‘b’ in an equation such as 2a + b are parameters that, when assigned specific values, yield a defined output. Similarly, in LLMs, parameters serve as adjustable values that govern the model’s behavior. However, the scale at which these parameters operate in LLMs is astronomical. For instance, OpenAI’s GPT-3, released in 2020, boasted a staggering 175 billion parameters. More recent models, like Google DeepMind’s Gemini 3, are speculated to possess upwards of a trillion parameters, with some estimates reaching as high as 7 trillion. The competitive landscape of AI development means that companies are increasingly secretive about the precise architecture and parameter counts of their cutting-edge models. Despite this secrecy, the fundamental nature and function of parameters remain consistent across different LLMs.

The process of assigning values to these parameters is driven by algorithms during the model’s training phase. Initially, each parameter is assigned a random value. The training process is an iterative cycle where the model makes predictions, identifies errors, and then uses an algorithm to adjust the parameter values to minimize those errors. This refinement continues over countless steps until the model consistently produces outputs that align with its intended function. Once training is complete, the values of these parameters become fixed, forming the model’s learned knowledge and capabilities.

The sheer scale of this training process is immense. For a model like GPT-3, each of its 175 billion parameters can be updated tens of thousands of times. This translates to quadrillions of individual calculations, demanding substantial computational resources and energy. The need for thousands of specialized high-speed computers running for months underscores the immense effort involved in training these sophisticated AI systems.

Within an LLM, parameters can be broadly categorized into three main types: embeddings, weights, and biases. Each plays a distinct role in how the model processes and understands language.

Embeddings are the numerical representations of words or sub-word units (tokens) within the LLM’s vocabulary. This vocabulary, typically comprising hundreds of thousands of unique tokens, is predefined by the model’s designers. However, the meaning of these tokens is not inherent; it is learned during the training process. When a model is trained, each word in its vocabulary is assigned a numerical vector—an embedding—that captures its meaning in relation to all other words, based on its usage in the vast training dataset.

This numerical value, the embedding, is not a single number but a list of numbers. Each number in this list represents a different facet of the word’s meaning as interpreted by the model from the training data. The length of this list, known as the dimensionality of the embedding, is another design choice made by LLM engineers. A common dimensionality is 4,096. An LLM with embeddings of 4,096 dimensions essentially represents each word as a point in a 4,096-dimensional space. The number 4,096 is often chosen because it is a power of two, a common preference in computing for efficiency. Embeddings with higher dimensions can capture more nuanced information about word usage, context, and subtle connotations, contributing to the model’s enhanced capability. Conversely, embeddings with too many dimensions can make training and running the model prohibitively expensive or slow.

This high-dimensional representation of words allows LLMs to map semantic relationships. Words with similar meanings are positioned closer together in this abstract space. For example, "table" and "chair" would be closer than "table" and "astronaut." OpenAI’s GPT-4.5, with an estimated over 10 trillion parameters, can reportedly process even more subtle cues, like emotional tones in text, by leveraging these extensive dimensions. Essentially, an LLM compresses the vastness of the internet into a monumental mathematical structure that encodes an immense amount of interconnected information, explaining both its remarkable abilities and its inherent complexity.

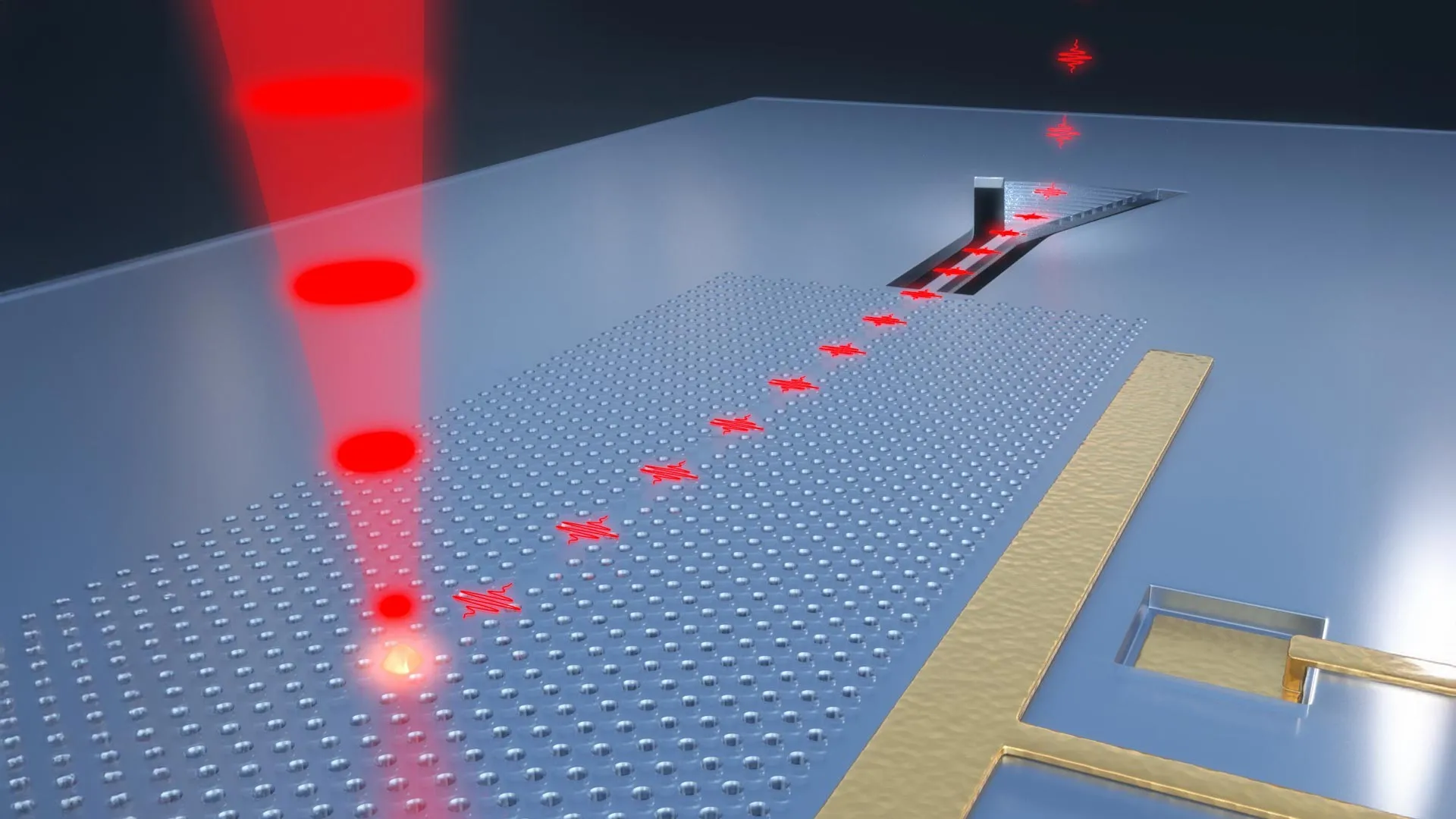

Weights are another crucial type of parameter, representing the strength of connections between different components of the model. When an LLM processes text, it first accesses the embeddings for each word. These embeddings are then fed through a series of neural networks, specifically transformers, which are designed to handle sequential data like text. Within these transformers, weights play a vital role in modulating the meaning of a word based on its specific context within a sentence. This involves multiplying each word’s embedding by the weights associated with other words in the sequence, thereby refining its contextual understanding.

Biases are parameters that complement the function of weights. While weights determine the thresholds at which different parts of the model activate, biases adjust these thresholds. This allows for activation even when an embedding’s value is low, ensuring that subtle information is not missed. Biases are added to embeddings, rather than multiplied, effectively acting as a sensitivity adjustment. In a noisy environment, weights might amplify the loudest signals, while biases would enhance the detection of quieter signals. Together, weights and biases are the mechanisms by which LLMs extract the richest possible information from the text they process, and their values are meticulously fine-tuned during training.

Neurons, while fundamental to the structure of LLMs, are not parameters themselves. Instead, they serve as organizational units that house parameters like weights and biases. These neurons are interconnected, loosely inspired by biological neurons, where signals propagate from one to another. Each neuron typically contains a single bias and weights corresponding to each dimension of the model’s embeddings. For a model with 4,096 dimensions, a neuron would hold one bias and 4,096 weights. Neurons are organized into layers, with each neuron in one layer often connected to every neuron in the next. A model like GPT-3, with approximately 100 layers, can contain tens of thousands of neurons per layer, each performing numerous computations simultaneously.

When an LLM processes text, the numerical representation of that input—the embedding—traverses through multiple layers. In each layer, the embedding’s value is repeatedly updated through computations involving the model’s weights and biases. This iterative process continues until the final layer, where the accumulated computations encapsulate the full meaning, nuance, and context of the input text. This final, transformed embedding is then used to predict the most likely subsequent word. The model doesn’t just pick the single most probable word; it calculates the probability of every word in its vocabulary appearing next and selects from a ranked list.

Beyond these core parameters, LLM designers also utilize "hyperparameters" to fine-tune the model’s output. These include "temperature," which acts as a creativity dial, influencing whether the model selects highly probable words for factual output or less probable words for more creative and surprising responses. "Top-p" and "top-k" are other hyperparameters that control the selection of the next word by restricting the choice to a pool of the most probable options, impacting the model’s perceived quirkiness or trustworthiness.

The recent trend of smaller models outperforming larger ones is a significant area of AI research. This efficiency can be achieved through several strategies. Firstly, the sheer volume of training data is critical; a smaller model trained on extensive data can surpass a larger model with less data. Meta’s Llama models exemplify this: the smaller Llama 3, trained on significantly more text than the larger Llama 2, is the superior model. Secondly, "overtraining"—exposing models to far more data than traditionally deemed necessary—enhances performance. Thirdly, "distillation" involves using a larger, pre-trained model to train a smaller one, effectively transferring knowledge. Furthermore, modern LLMs often employ a "mixture of experts" approach, where large models are composed of specialized smaller models that activate only when relevant, combining the power of large models with the efficiency of smaller ones. This indicates a shift from merely increasing parameter count to optimizing how parameters are utilized, emphasizing "what you do with them" rather than "how many you have."