Mushrooms, often overlooked for their intricate underground networks and resilience, possess a suite of "toughness and unusual biological properties" that make them unexpectedly attractive candidates for the burgeoning field of bioelectronics. This interdisciplinary domain, at the nexus of biology and technology, is dedicated to the design of innovative, sustainable materials poised to redefine the landscape of future computing systems. The Ohio State team has demonstrated that these humble organisms can be meticulously cultivated and guided to function as organic memristors, fundamental components akin to memory cells that possess the crucial ability to retain information about their previous electrical states.

The implications of this discovery are far-reaching. The researchers’ experiments have conclusively shown that these mushroom-based devices can replicate the complex memory behavior characteristic of conventional semiconductor chips. Beyond mere replication, this fungal approach holds the promise of enabling the creation of other eco-friendly, brain-like computing tools that boast a significantly lower production cost. Dr. John LaRocco, the lead author of the study and a research scientist in psychiatry at Ohio State’s College of Medicine, articulated the profound advantages of this bio-integrated approach. "Being able to develop microchips that mimic actual neural activity means you don’t need a lot of power for standby or when the machine isn’t being used," he explained. "That’s something that can be a huge potential computational and economic advantage." This inherent energy efficiency, mirroring the low-power demands of biological neural networks, could drastically reduce the energy footprint of computing devices, a critical concern in an increasingly digitized world.

The concept of fungal electronics, while not entirely novel, is rapidly evolving from theoretical exploration to practical application, particularly in the context of sustainable computing. The inherent biodegradability and low production cost of fungal materials offer a compelling solution to the escalating problem of electronic waste, a persistent environmental challenge. In stark contrast, traditional semiconductors often rely on the extraction of rare minerals and demand substantial energy inputs for both their manufacture and operation. "Mycelium as a computing substrate has been explored before in less intuitive setups, but our work tries to push one of these memristive systems to its limits," LaRocco emphasized, highlighting the ambition to push the boundaries of what’s possible with these organic materials. The team’s pivotal findings, underscoring the viability of their approach, were recently published in the esteemed scientific journal PLOS One.

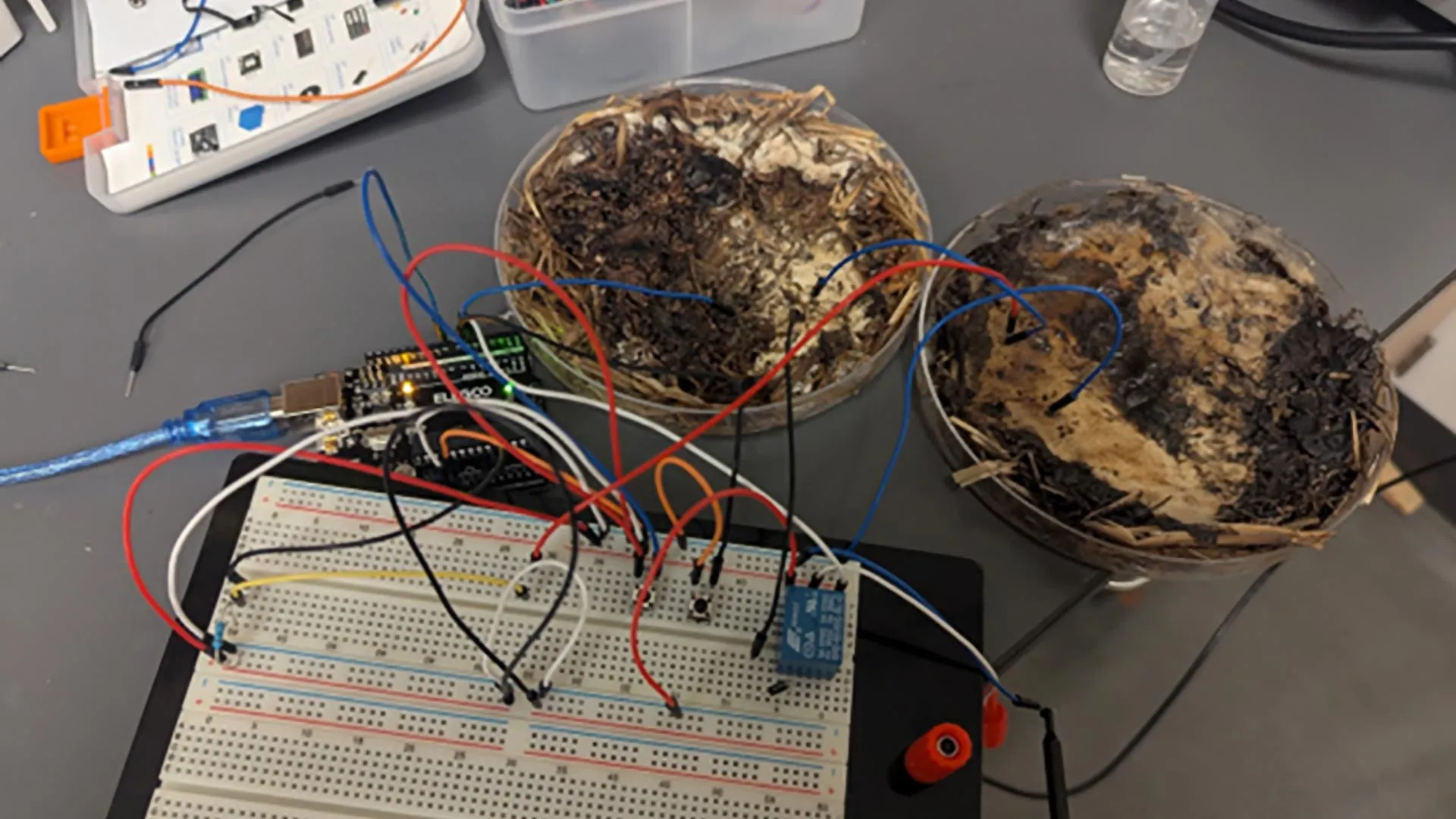

The experimental methodology employed by the researchers to test the memory capabilities of mushrooms was both ingenious and meticulous. Samples of shiitake and button mushrooms were carefully cultivated. Upon reaching maturity, these specimens were meticulously dehydrated to ensure their preservation and then integrated into custom-designed electronic circuits. The experimental setup involved exposing these mushroom-based devices to precisely controlled electric currents, meticulously varying the applied voltages and frequencies. "We would connect electrical wires and probes at different points on the mushrooms because distinct parts of it have different electrical properties," LaRocco elaborated. "Depending on the voltage and connectivity, we were seeing different performances." This detailed approach allowed the team to map the electrical behavior of different regions within the mushroom structure.

The results emerging from these intricate "mushroom circuits" were nothing short of surprising. After a rigorous two-month testing period, the researchers observed that their mushroom-based memristor exhibited a remarkable ability to switch between electrical states an astonishing 5,850 times per second, achieving an accuracy of approximately 90%. While a decline in performance was noted at higher electrical frequencies, a significant breakthrough occurred when the team discovered that interconnecting multiple mushrooms enhanced stability, effectively restoring performance. This emergent property closely mirrors the interconnected nature of neural pathways in the human brain, suggesting a natural synergy between fungal structures and computational principles.

Qudsia Tahmina, a co-author of the study and an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Ohio State, underscored the remarkable adaptability of mushrooms for computing applications. "Society has become increasingly aware of the need to protect our environment and ensure that we preserve it for future generations," Tahmina stated. "So that could be one of the driving factors behind new bio-friendly ideas like these." This growing environmental consciousness is acting as a powerful catalyst for innovation in the realm of sustainable technology. Furthermore, Tahmina highlighted the inherent flexibility offered by mushrooms, suggesting vast possibilities for scaling up fungal computing. This scalability opens doors for diverse applications, ranging from edge computing and advanced aerospace exploration utilizing larger fungal systems to enhancing the performance of autonomous systems and wearable devices through smaller, integrated fungal components.

Looking ahead, the future of fungal computing, while still in its nascent stages, is brimming with promise. The scientific community is actively pursuing the refinement of cultivation methods and the miniaturization of device sizes. Achieving smaller, more efficient fungal components will be the linchpin in establishing them as a viable and competitive alternative to traditional microchips. Dr. LaRocco painted an optimistic picture of accessibility and scalability: "Everything you’d need to start exploring fungi and computing could be as small as a compost heap and some homemade electronics, or as big as a culturing factory with pre-made templates," he remarked. "All of them are viable with the resources we have in front of us now." This suggests a democratic approach to innovation, where even rudimentary setups can yield valuable insights, alongside the potential for large-scale industrial implementation. The research was further bolstered by contributions from other Ohio State researchers, including Ruben Petreaca, John Simonis, and Justin Hill, and received crucial support from the Honda Research Institute, underscoring the collaborative and well-supported nature of this pioneering endeavor.