The implications of this discovery are profound. The Ohio State team’s experiments have shown that these mushroom-based devices can replicate the memory behavior observed in traditional semiconductor chips. More importantly, this research opens the door to creating eco-friendly, brain-like computing tools that are significantly less expensive to produce than their silicon-based counterparts. John LaRocco, the lead author of the study and a research scientist in psychiatry at Ohio State’s College of Medicine, highlights the transformative potential: "Being able to develop microchips that mimic actual neural activity means you don’t need a lot of power for standby or when the machine isn’t being used. That’s something that can be a huge potential computational and economic advantage." This inherent energy efficiency, particularly in standby modes, could dramatically reduce the power consumption of future electronic devices, leading to substantial energy savings and a smaller carbon footprint.

The promise of fungal electronics extends far beyond mere cost reduction and energy efficiency. While the concept of using fungal materials for electronics isn’t entirely new, its practical application for sustainable computing is rapidly advancing. Fungal materials offer a distinct advantage in terms of sustainability: they are biodegradable and inexpensive to produce, directly addressing the growing problem of electronic waste. In stark contrast, conventional semiconductors often rely on rare earth minerals, whose extraction can be environmentally damaging, and require immense amounts of energy for their manufacturing and operation. LaRocco elaborates on this crucial aspect: "Mycelium as a computing substrate has been explored before in less intuitive setups, but our work tries to push one of these memristive systems to its limits." This drive to push the boundaries of fungal computing is what sets this research apart, moving from theoretical exploration to demonstrable functionality. The team’s pioneering findings have been formally published in the esteemed scientific journal PLOS One, marking a significant milestone in the field.

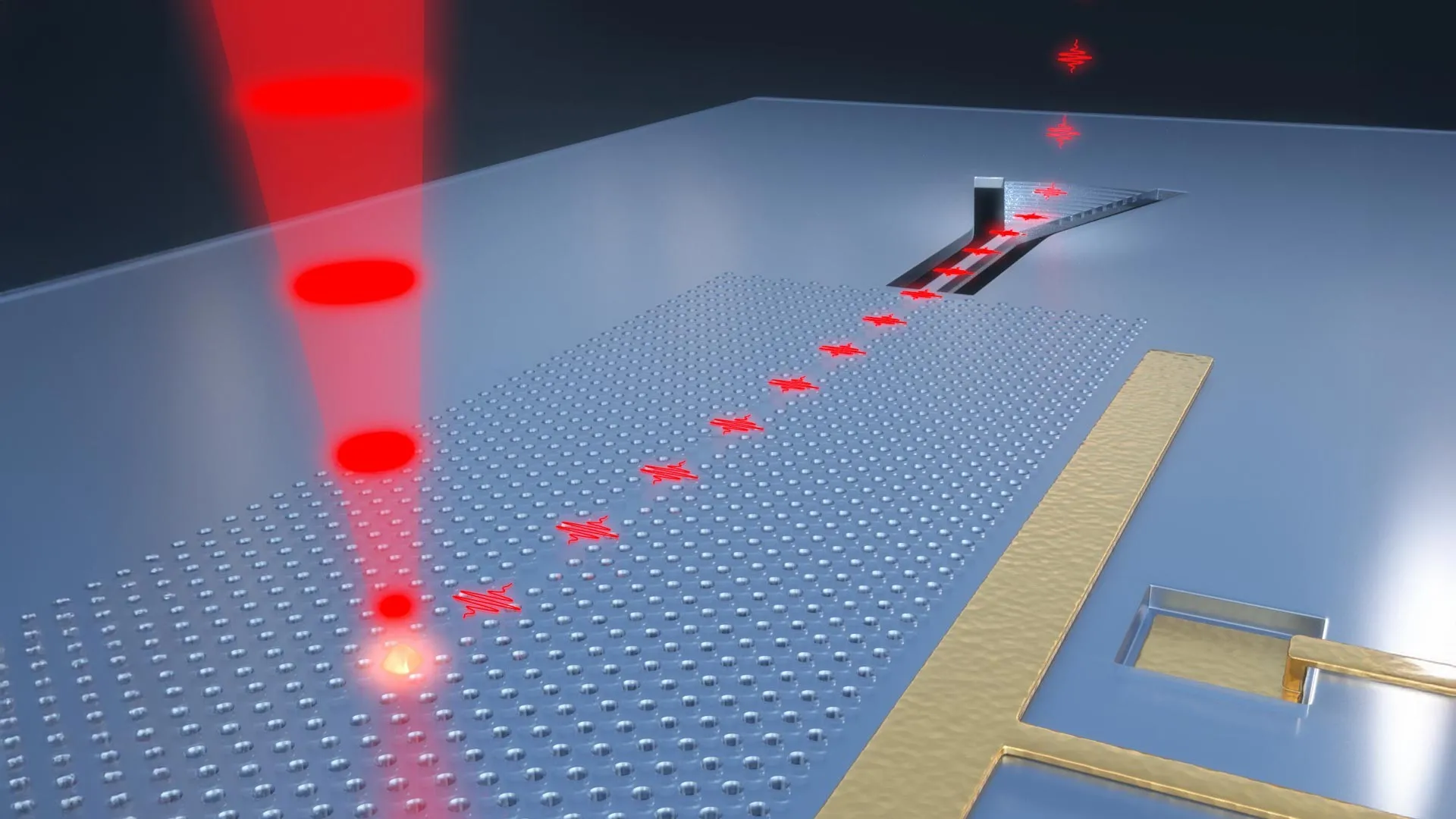

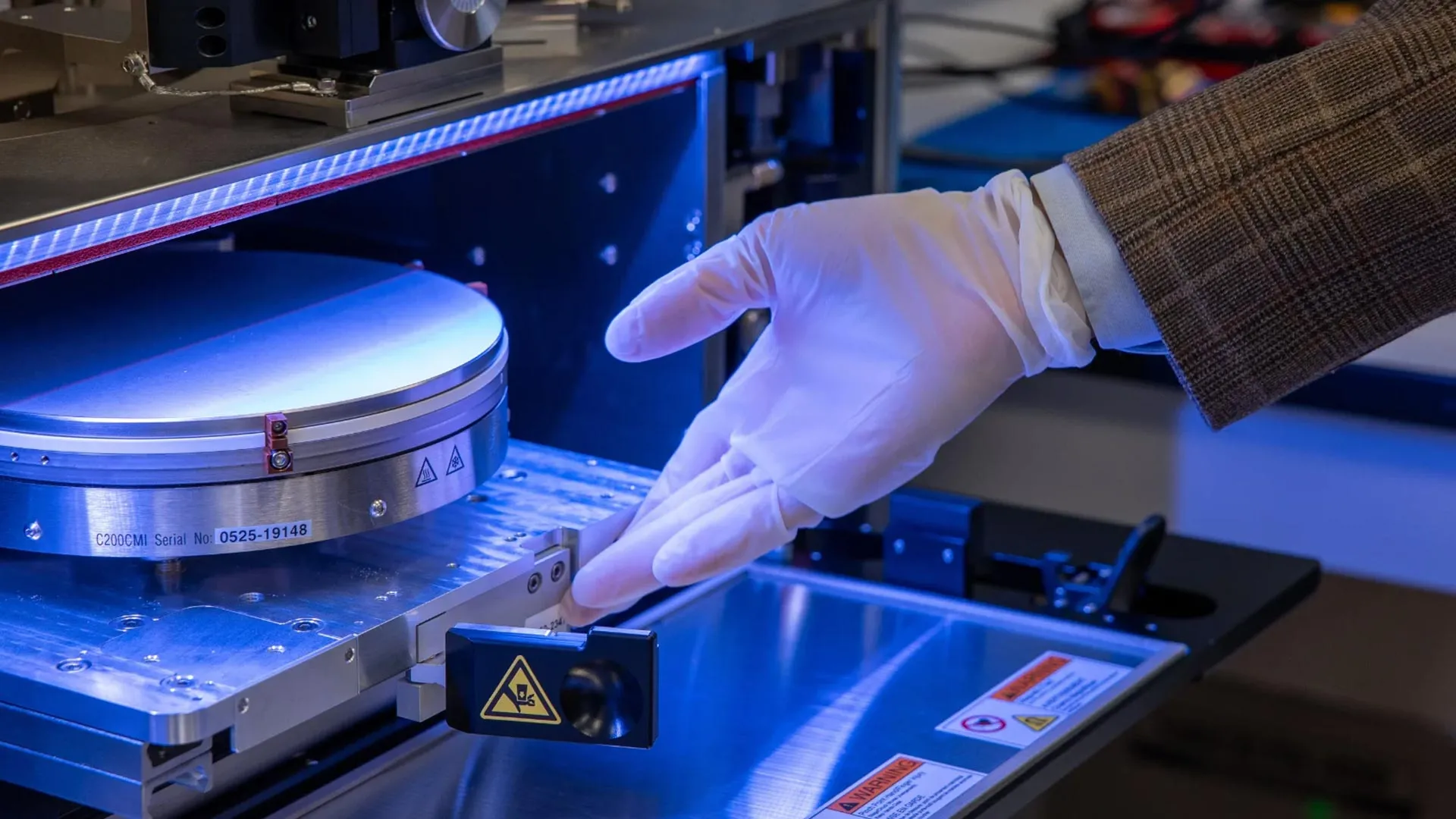

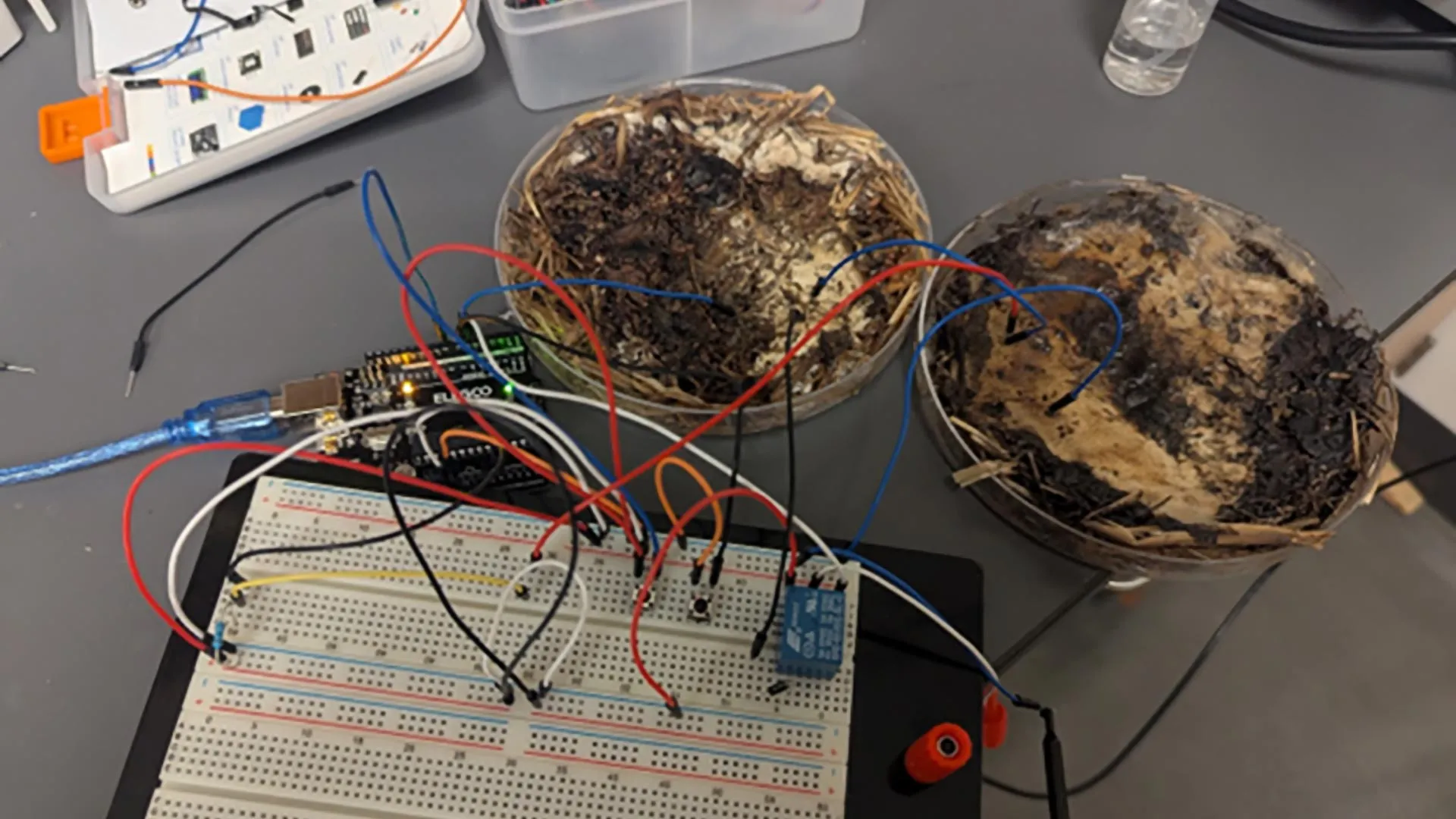

The scientific rigor behind these claims was put to the test through a series of meticulous experiments. Researchers began by cultivating samples of both shiitake and button mushrooms. Once the mushrooms reached maturity, they were carefully dehydrated. This crucial step preserves the fungal structure while rendering it suitable for integration into electronic circuits. The dehydrated mushrooms were then attached to custom-designed electronic circuits. The core of the experimentation involved exposing these mushroom-based circuits to controlled electric currents, varying the voltages and frequencies to observe their behavior. LaRocco explains the experimental setup: "We would connect electrical wires and probes at different points on the mushrooms because distinct parts of it have different electrical properties. Depending on the voltage and connectivity, we were seeing different performances." This precise approach allowed the researchers to probe the unique electrical characteristics of the fungal material and understand how it responded to electrical stimuli.

The results of these extensive tests were nothing short of surprising and highly encouraging. After a rigorous two-month testing period, the researchers discovered that their mushroom-based memristor exhibited remarkable capabilities. It could reliably switch between different electrical states an impressive 5,850 times per second, achieving an accuracy rate of approximately 90%. While performance did naturally decline at higher electrical frequencies, a fascinating observation emerged: connecting multiple mushrooms together proved to be a highly effective strategy for restoring and enhancing stability. This phenomenon remarkably mirrors the way neural connections function in the human brain, where interconnected networks facilitate robust and efficient information processing. Qudsia Tahmina, a co-author of the study and an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Ohio State, emphasized the inherent adaptability of mushrooms for computing: "Society has become increasingly aware of the need to protect our environment and ensure that we preserve it for future generations. So that could be one of the driving factors behind new bio-friendly ideas like these." This societal shift towards environmental consciousness is a powerful motivator for developing sustainable technological solutions.

Furthermore, Tahmina points to the inherent flexibility of mushrooms as a key factor in scaling up fungal computing applications. The potential for growth is vast, ranging from large-scale systems suitable for edge computing and ambitious aerospace exploration to smaller, more compact units that could enhance the performance of autonomous systems and wearable devices. The adaptability of fungal materials suggests a future where computing power can be integrated into a wide array of applications, from the vastness of space to the intimacy of our personal devices.

Looking ahead, the path for fungal computing is clear, though still in its nascent stages. Scientists are intensely focused on refining cultivation methods and, crucially, shrinking the size of these organic components. The ultimate goal is to create fungal memristors that are not only efficient but also small enough to be a truly viable alternative to traditional microchips. LaRocco encapsulates the accessibility of this burgeoning technology: "Everything you’d need to start exploring fungi and computing could be as small as a compost heap and some homemade electronics, or as big as a culturing factory with pre-made templates. All of them are viable with the resources we have in front of us now." This statement underscores the democratic nature of this research, suggesting that experimentation and development can occur at various scales, from amateur enthusiasts to industrial giants. The research team at Ohio State, including Ruben Petreaca, John Simonis, and Justin Hill, with support from the Honda Research Institute, is at the forefront of this exciting journey, heralding a future where our computers are not just built, but grown.