The journey to this remarkable discovery began with a serendipitous observation by Tyler Cocker, an associate professor in Michigan State University’s College of Natural Science, and Jose L. Mendoza-Cortes, an assistant professor spanning both the College of Engineering and the College of Natural Science. Their collaborative efforts, bridging the gap between practical experimentation and profound theoretical understanding, have pushed the boundaries of materials science and its application in electronic technologies. "This experience has been a reminder of what science is really like because we found materials that are working in ways that we didn’t expect," remarked Cocker, highlighting the inherent unpredictability and excitement of scientific exploration. "Now, we want to look at something that is going to be technologically interesting for people in the future."

At the heart of their research lies a fascinating material known as tungsten ditelluride (WTe2). This compound, composed of a central layer of tungsten (W) atoms sandwiched between two layers of tellurium (Te) atoms, possesses unique electronic characteristics. Cocker’s team employed a highly specialized scanning tunneling microscope (STM), a sophisticated instrument that goes far beyond the capabilities of conventional microscopes. While typical microscopes are designed to magnify the unseen, such as individual cells, Cocker’s STM can visualize individual atoms on a material’s surface. It achieves this by meticulously guiding an incredibly sharp metal tip across the surface, sensing the atomic landscape through subtle electrical signals – a process akin to reading Braille at the atomic level.

During their detailed atomic-level examination of WTe2, Cocker and his colleagues introduced a powerful, ultra-fast laser. This laser generated terahertz pulses of light, oscillating at an astonishing speed of hundreds of trillions of times per second. These potent pulses were precisely directed onto the STM tip. The intense energy of these terahertz pulses, amplified at the tip’s apex, exerted a controlled force on the topmost layer of WTe2 atoms directly beneath it. This laser-induced energy was sufficient to gently "wiggle" these surface atoms, subtly displacing them from their original alignment with the underlying atomic layers. The researchers likened this phenomenon to a stack of papers where the top sheet has been slightly askew.

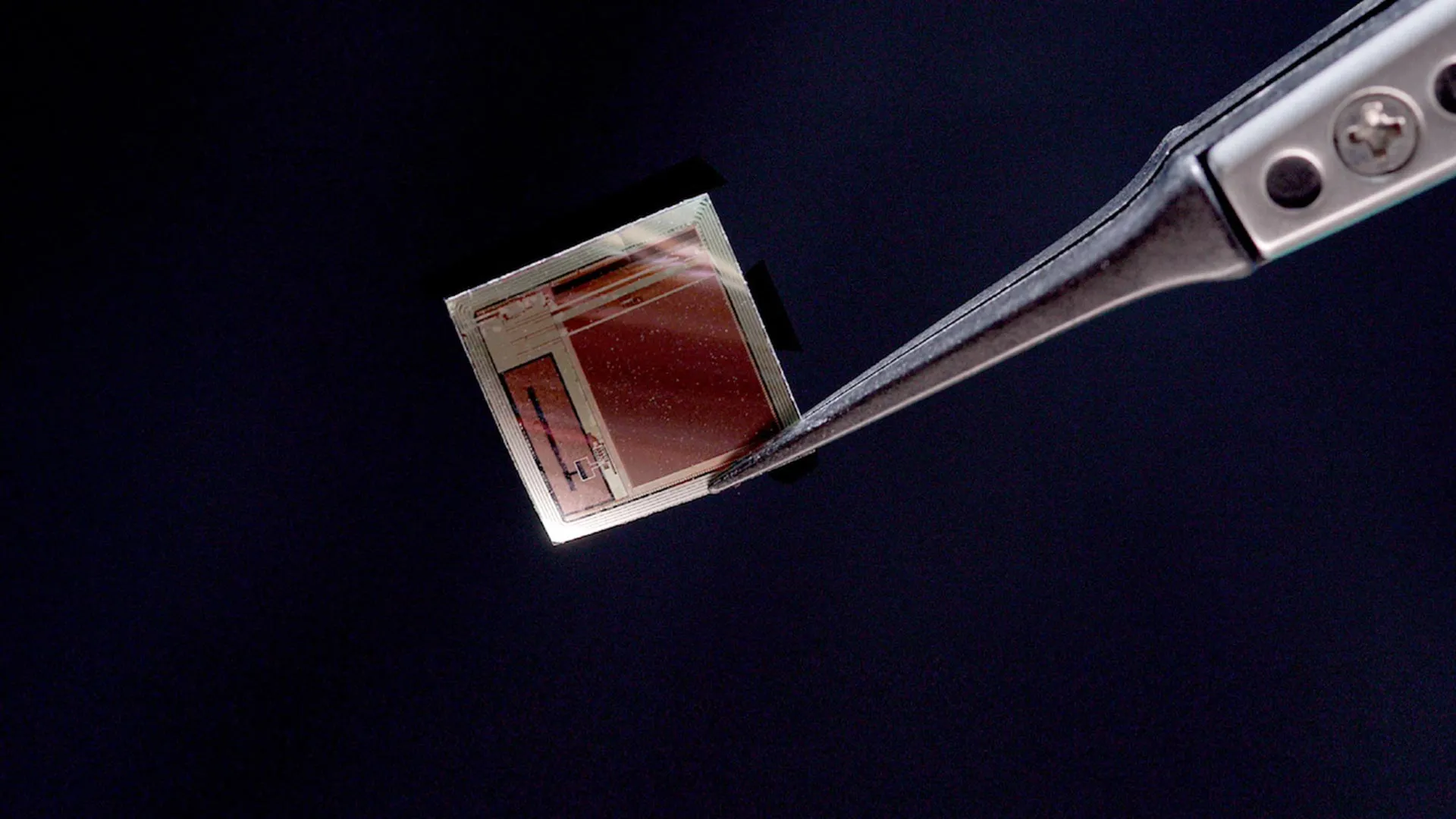

The immediate consequence of this laser illumination was profound. The top atomic layer of the WTe2, when energized by the terahertz pulses and the STM tip, began to exhibit entirely new electronic properties. These emergent behaviors were absent when the laser was deactivated, underscoring the material’s dynamic responsiveness to external stimuli. Cocker and his team recognized the immense potential of this interaction. They realized that the combination of terahertz pulses and the STM tip could function as a nanoscale switch, capable of temporarily reconfiguring the electrical characteristics of WTe2. This discovery opens up exciting possibilities for enhancing the performance and efficiency of next-generation electronic devices. Remarkably, the advanced STM was not only able to induce these atomic movements but also to capture visual evidence of them, effectively photographing the unique "on" and "off" states of the atomic switch they had engineered.

The synergy between experimental observation and theoretical prediction proved crucial in fully understanding this phenomenon. As Cocker and Mendoza-Cortes discovered they were independently pursuing related lines of inquiry, their respective approaches – Cocker’s experimental prowess and Mendoza-Cortes’ theoretical modeling – converged. Mendoza-Cortes’ research centers on developing sophisticated computer simulations that delve into the intricacies of quantum mechanics. By rigorously comparing the outcomes of Mendoza-Cortes’ quantum calculations with the experimental data gathered by Cocker’s team, both laboratories arrived at identical conclusions, validating their findings through distinct methodologies. "Our research is complementary; it’s the same observations but through different lenses," explained Mendoza-Cortes. "When our model matched the same answers and conclusions they found in their experiments, we have a better picture of what is going on."

Further computational analysis from Mendoza’s lab provided invaluable quantitative insights. They precisely calculated that the layers of WTe2 shift by an astonishingly small 7 picometers during their laser-induced wiggling. This minute displacement, while challenging for even specialized microscopes to fully resolve on their own, was clearly elucidated through their theoretical framework. Moreover, their quantum calculations confirmed that the frequencies at which the atoms oscillate, as observed in experiments, were in perfect agreement with theoretical predictions. Crucially, the simulations also revealed the precise direction and magnitude of these atomic movements, offering a comprehensive understanding of the underlying quantum mechanics.

Daniel Maldonado-Lopez, a fourth-year graduate student in Mendoza’s lab, emphasized the localized nature of this effect: "The movement only occurs on the topmost layer, so it is very localized. This can potentially be applied in building faster and smaller electronics." This precision and control at the atomic scale are precisely what the field of electronics has been striving for.

The ultimate vision of Cocker and Mendoza-Cortes is to translate this fundamental research into tangible technological advancements. They aspire for their work to usher in the era of novel materials with enhanced properties, leading to reduced manufacturing costs, significantly faster processing speeds, and a marked improvement in energy efficiency for future generations of smartphones and computer technology. Stefanie Adams, a fourth-year graduate student in Cocker’s lab, eloquently articulated the significance of material selection in electronics: "When you think about your smartphone or your laptop, all of the components that are in there are made out of a material. At some point, someone decided that’s the material we’re going use." This research signifies a paradigm shift in that decision-making process, offering a new level of control and a broader palette of possibilities for material design.

This groundbreaking research, detailing the laser-induced dance of atoms and its implications for future electronics, was published in the prestigious journal Nature Photonics. The work received partial support through the computational resources and services provided by the Institute for Cyber-Enabled Research at Michigan State University, underscoring the vital role of interdisciplinary collaboration and advanced computational infrastructure in driving scientific discovery. The implications of this research are far-reaching, suggesting that the ability to precisely manipulate matter at the atomic level using light could fundamentally alter how we design, build, and interact with the electronic devices that shape our modern lives. The control demonstrated over atomic behavior opens avenues for entirely new paradigms in information processing, data storage, and energy management, moving us closer to devices that are not only more powerful but also more sustainable. The ability to dynamically alter material properties on demand, as demonstrated with WTe2, hints at the potential for reconfigurable electronics, where devices could adapt their functionality based on user needs or environmental conditions, blurring the lines between hardware and software. This research is not just about making existing technologies better; it’s about imagining and creating entirely new ones, powered by a deeper understanding and mastery of the quantum realm.