At the forefront of this transformative research are Tyler Cocker, an associate professor in the College of Natural Science, and Jose L. Mendoza-Cortes, an assistant professor in both the Colleges of Engineering and Natural Science. Their collaborative effort has elegantly fused the experimental prowess of quantum mechanics with its theoretical underpinnings, pushing the boundaries of material science to revolutionize everyday electronic technologies. This endeavor has not only yielded novel applications but has also served as a potent reminder of the serendipitous nature of scientific discovery, as Cocker noted, "This experience has been a reminder of what science is really like because we found materials that are working in ways that we didn’t expect. Now, we want to look at something that is going to be technologically interesting for people in the future."

The cornerstone of their experiments is a material known as tungsten ditelluride, or WTe2. This fascinating compound is structured with a single layer of tungsten (W) atoms meticulously sandwiched between two layers of tellurium (Te) atoms. Cocker’s team employed a highly specialized scanning tunneling microscope (STM) of their own design. While conventional microscopes are adept at visualizing microscopic entities like cells, Cocker’s STM possesses the extraordinary capability to resolve individual atoms on a material’s surface. This remarkable feat is achieved by guiding an ultra-sharp metal tip across the surface, meticulously "feeling" the atomic landscape through subtle electrical signals, akin to reading Braille.

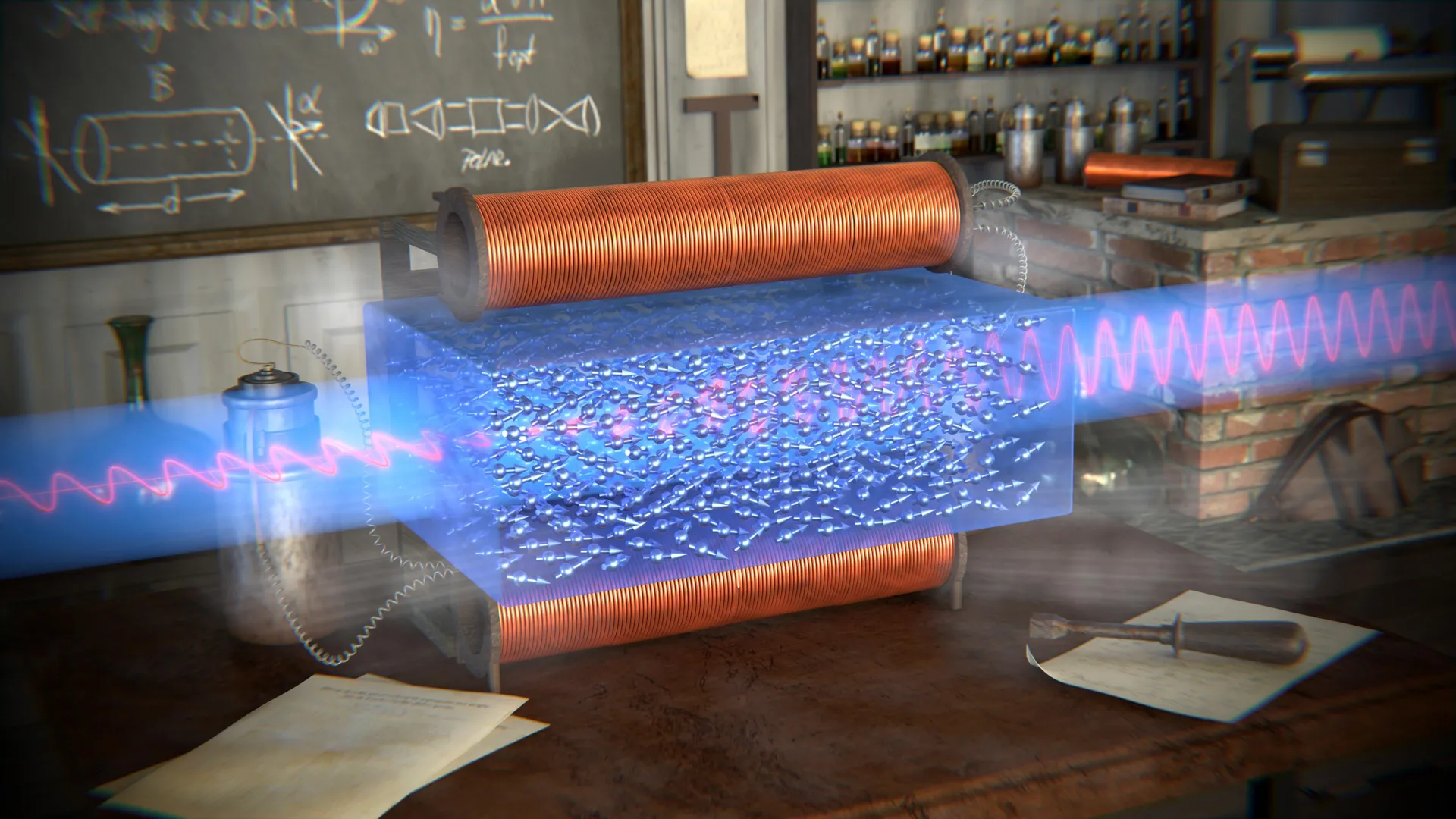

During their investigations of WTe2’s atomic surface, Cocker and his colleagues unleashed the power of a super-fast laser. This laser generated terahertz pulses of light, oscillating at astonishing speeds of hundreds of trillions of times per second. These intense terahertz pulses were precisely focused onto the tip of the STM. At this critical juncture, the laser’s energy was amplified dramatically, empowering the researchers to induce controlled vibrations in the uppermost layer of atoms directly beneath the tip. This precise manipulation allowed them to gently coax this top atomic layer out of its natural alignment with the underlying layers, creating a subtle, yet significant, displacement – a phenomenon aptly described as a slightly crooked top sheet in a stack of papers.

The profound impact of this laser-induced atomic dance became evident when the terahertz pulses illuminated both the STM tip and the WTe2 material. The top atomic layer of the material exhibited a marked change in its behavior, displaying novel electronic properties that were conspicuously absent when the laser was deactivated. Cocker and his team recognized the immense potential of these terahertz pulses, in conjunction with the STM tip, to function as a nanoscale switch. This switch could be employed to temporarily modulate the electrical characteristics of WTe2, paving the way for the development of next-generation electronic devices with enhanced capabilities. The precision of Cocker’s microscope was so refined that it could not only observe the atomic movements during this process but also capture photographic evidence of the distinct "on" and "off" states of the sophisticated switch they had engineered.

A pivotal moment in their research occurred when Cocker and Mendoza-Cortes discovered that their individual projects, though pursued from different angles, were converging on similar scientific questions. Cocker’s experimental expertise seamlessly complemented Mendoza-Cortes’ theoretical investigations into quantum mechanics. Mendoza-Cortes’ research is primarily focused on the creation of sophisticated computer simulations. By meticulously comparing the outcomes of Mendoza-Cortes’ quantum calculations with Cocker’s experimental data, both laboratories arrived at the same conclusions, remarkably and independently, utilizing entirely distinct methodologies and tools.

"Our research is complementary; it’s the same observations but through different lenses," explained Mendoza-Cortes. "When our model matched the same answers and conclusions they found in their experiments, we have a better picture of what is going on." This synergistic approach provided a more comprehensive and robust understanding of the underlying physics at play.

The Mendoza lab’s computational simulations provided crucial quantitative insights. They determined that the layers of WTe2 shift by an incredibly small margin of 7 picometers during their induced oscillations. This minute displacement, while difficult to discern solely through the specialized microscope, was definitively captured by their theoretical model. Furthermore, their quantum calculations corroborated the frequencies at which the atoms vibrate, aligning perfectly with experimental observations. Crucially, the theoretical framework offered an even deeper understanding, revealing not only the magnitude but also the precise direction of these atomic wiggles.

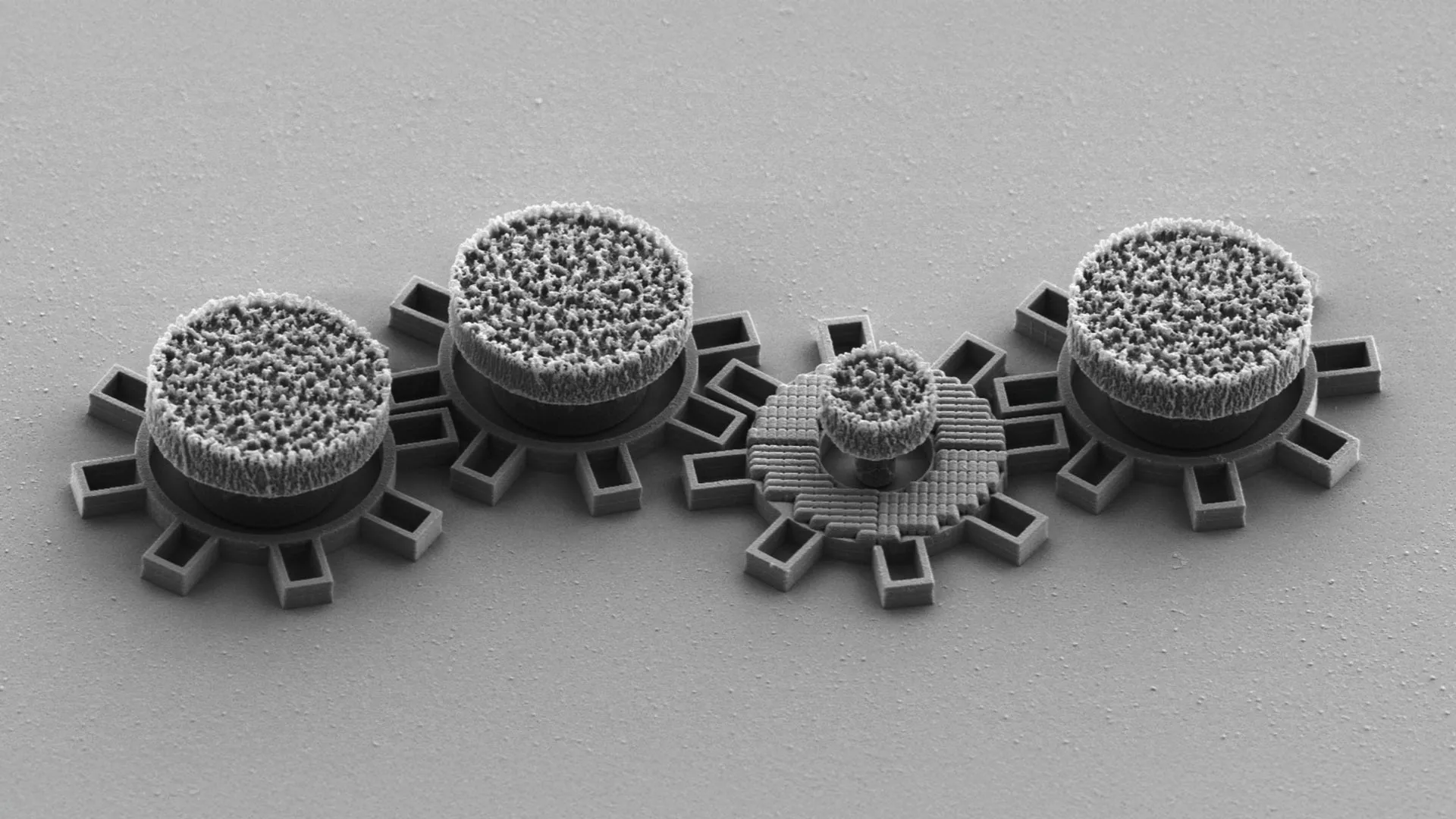

Daniel Maldonado-Lopez, a fourth-year graduate student in Mendoza’s lab, highlighted the localized nature of this phenomenon: "The movement only occurs on the topmost layer, so it is very localized. This can potentially be applied in building faster and smaller electronics." This targeted control over atomic behavior at the surface is a key enabler for miniaturization and performance enhancement.

The ultimate aspiration of Cocker and Mendoza-Cortes is to translate this fundamental research into tangible technological advancements. They envision a future where this discovery leads to the adoption of novel materials, reduced manufacturing costs, significantly faster processing speeds, and substantially improved energy efficiency for ubiquitous devices like smartphones and advanced computing systems. Stefanie Adams, a fourth-year graduate student in Cocker’s lab, eloquently articulated the significance of material selection in technology: "When you think about your smartphone or your laptop, all of the components that are in there are made out of a material. At some point, someone decided that’s the material we’re going use." This research aims to inform and inspire those crucial material decisions for the future.

The pioneering findings of this research have been published in the prestigious journal Nature Photonics, a testament to its scientific rigor and impact. The work was generously supported in part by the computational resources and services provided by the Institute for Cyber-Enabled Research at Michigan State University, underscoring the vital role of institutional support in advancing cutting-edge scientific endeavors.

The implications of this research are far-reaching. By learning to precisely control and manipulate the atomic behavior of materials using lasers, scientists are unlocking new paradigms for electronic device design. This ability to dynamically alter material properties at the atomic level opens doors to creating transistors that are orders of magnitude smaller and more energy-efficient. Imagine smartphones that can perform complex computations with minimal battery drain, or wearable devices that are incredibly powerful yet barely noticeable. The potential extends beyond personal electronics, impacting fields like quantum computing, advanced sensors, and even novel forms of data storage. The controlled dance of atoms, orchestrated by lasers, is not just a scientific curiosity; it is a fundamental step towards a future where our electronic world is more capable, efficient, and seamlessly integrated into our lives. The research at Michigan State University is a vivid demonstration of how exploring the fundamental quantum nature of matter can lead to tangible advancements that shape the technologies we rely on every day and will continue to do so for generations to come.