On the surface, the Superbox media streaming devices, readily available at major retailers like Best Buy and Walmart, present a compelling offer: unlimited access to over 2,200 pay-per-view and streaming services, including popular platforms such as Netflix, ESPN, and Hulu, all for a one-time payment of approximately $400. However, cybersecurity experts are sounding the alarm, revealing that these seemingly attractive TV boxes are equipped with intrusive software that effectively turns users’ home networks into relays for illicit internet traffic. This traffic is frequently linked to nefarious cybercriminal activities, ranging from sophisticated advertising fraud schemes to unauthorized account takeovers.

Superbox positions itself as an accessible solution for households seeking to stream a vast library of television and movie content without the recurring burden of monthly subscription fees. Their marketing, particularly on their website and in recent blog posts, emphasizes affordability and the elimination of "confusing cable bills and hidden fees." One blog post, titled "Cheap Cable TV for Low Income: Watch TV, No Monthly Bills," boldly states, "Real cheap cable TV for low income solutions does exist," and promises to guide readers toward alternatives that "stop overpaying," including "free over-the-air options to one-time purchase devices that eliminate monthly bills." Crucially, Superbox also claims that its devices and the act of streaming content do not violate U.S. copyright law, asserting, "SuperBox is just like any other Android TV box on the market, we can not control what software customers will use… And you won’t encounter a law issue unless uploading, downloading, or broadcasting content to a large group."

Legally, the sale and use of the Superbox itself are not inherently illicit. The device can be employed legitimately as a platform for streaming content from services where users already maintain paid subscriptions. However, the primary allure for consumers shelling out $400 is the promise of accessing over 2,200 channels without any ongoing costs. This is achieved by installing specific applications designed for the device that facilitate unauthorized streaming.

Superbox’s homepage prominently features a disclaimer stating, "We do not sell access to or preinstall any apps that bypass paywalls or provide access to unauthorized content." The company clarifies that they provide only the hardware, leaving the choice of applications entirely to the customer. "We only sell the hardware device," the notice continues. "Customers must use official apps and licensed services; unauthorized use may violate copyright law." While Superbox’s claim of selling only hardware is technically accurate, the assertion that customers "must use official apps and licensed services" is questionable. To access the thousands of channels advertised, users are required to configure the device to update itself, a process that necessitates replacing Google’s official Play Store with an unofficial alternative, such as the "App Store" or "Blue TV Store." This is because the Superbox does not run on the official Google-certified Android TV system, and its proprietary apps will not function otherwise. Only after the Google Play Store is supplanted by this unofficial store do the specialized streaming apps for Superbox become available for download, operating outside of Google’s established app ecosystem.

Security experts explain that while these Android streaming boxes generally fulfill their promise of enabling access to content that would typically require paid subscriptions, the applications that enable this streaming also inadvertently ensnare the user’s internet connection into a distributed residential proxy network. This network utilizes the compromised devices to relay traffic for other users. Ashley, a senior solutions engineer at cyber intelligence firm Censys, who requested her first name be used for privacy, has been studying several Superbox models in Censys’s malware lab, including one purchased from Best Buy. In a video interview, she highlighted the deceptive nature of these devices, noting, "I’m sure a lot of people are thinking, ‘Hey, how bad could it be if it’s for sale at the big box stores?’ But the more I looked, things got weirder and weirder."

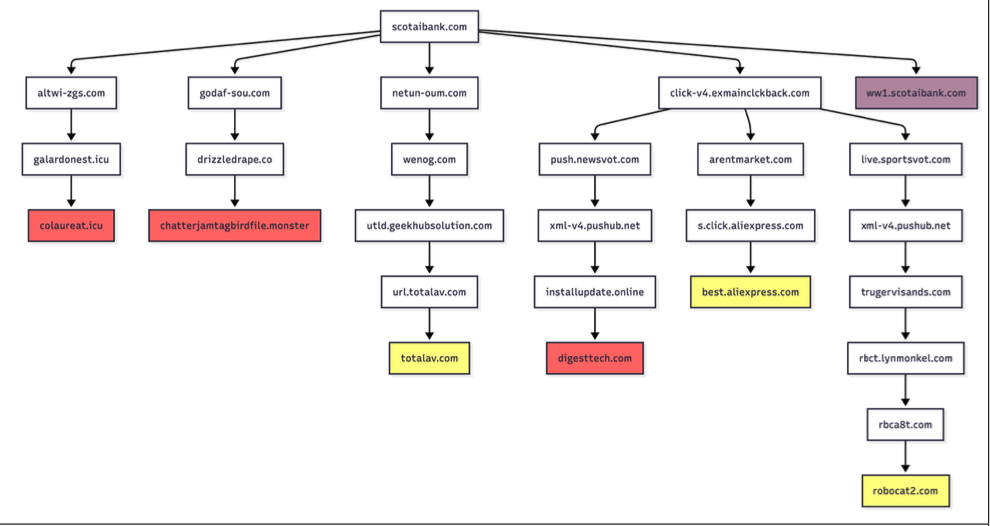

Ashley’s investigation revealed that Superbox devices immediately establish contact with a server belonging to the Chinese instant messaging service Tencent QQ, as well as a residential proxy service known as Grass IO. Grass, operating under the domain getgrass[.]io, describes itself as "a decentralized network that allows users to earn rewards by sharing their unused Internet bandwidth with AI labs and other companies." Their website further explains that buyers seek unused internet bandwidth to access a diverse range of IP addresses, facilitating market research and tasks like web scraping for AI training.

Andrej Radonjic, founder of Grass, expressed unfamiliarity with Superbox when contacted via Twitter/X, stating that Grass has no affiliation with the device manufacturer. He commented, "It looks like these boxes are distributing an unethical proxy network which people are using to try to take advantage of Grass. The point of grass is to be an opt-in network. You download the grass app to monetize your unused bandwidth. There are tons of sketchy SDKs out there that hijack people’s bandwidth to help webscraping companies." Radonjic affirmed that Grass employs robust systems to identify and block network abusers, preventing them from earning rewards if they attempt to misuse the service.

Superbox’s parent company, Super Media Technology Company Ltd., lists a UPS store in Fountain Valley, California, as its physical address and did not respond to multiple inquiries. A teardown by behindmlm.com, a blog that scrutinizes multi-level marketing schemes, indicates that Grass’s compensation plan is based on "grass points," earned through app usage and by recruiting affiliates. While affiliates can earn points for contributing bandwidth, reaching higher tiers and redeeming these points for potential cryptocurrency rewards requires accumulating millions of points or recruiting a significant number of other users. Radonjic acknowledged Grass has undergone "a handful of corporate clean-ups" in its two-year existence, attributing them to administrative changes and early-stage restructuring under the Grass Foundation.

Upon examining the Superbox devices, Ashley identified the immediate connection to Tencent QQ as a primary concern. She also discovered the inclusion of powerful network analysis and remote access tools like Tcpdump and Netcat, which are unusual for a typical streaming device. "This thing DNS hijacked my router, did ARP poisoning to the point where things fall off the network so they can assume that IP, and attempted to bypass controls," she reported. "I have root on all of them now, and they actually have a folder called ‘secondstage.’ These devices also have Netcat and Tcpdump on them, and yet they are supposed to be streaming devices."

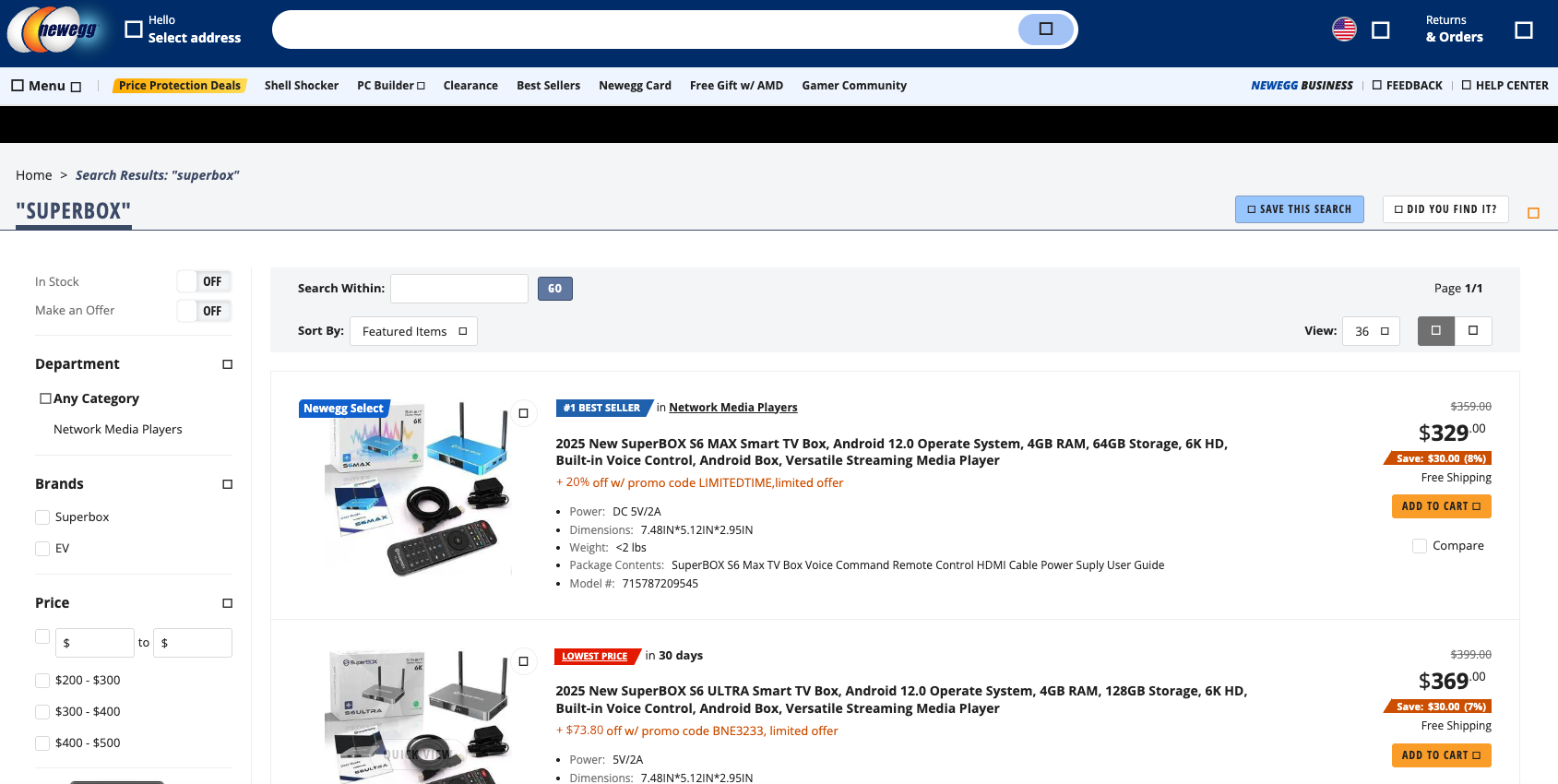

A cursory online search reveals a vast array of Superbox models and similar Android streaming devices available on prominent e-commerce platforms, including Amazon, Best Buy, Newegg, and Walmart. While these products are typically sold by third-party merchants, many are fulfilled directly by the e-commerce platforms themselves. Ashley noted that Newegg has become a significant marketplace for these devices, with eBay also featuring them, even under the Spanish moniker "SuperCaja." While Amazon has reportedly taken steps to crack down on Superbox listings, similar devices can still be found under more generic terms like "modem and router combo," which Ashley suggests is a more accurate description of their function.

Superbox does not engage in traditional advertising, instead relying on lesser-known influencers on platforms like YouTube and TikTok to promote their products. These influencers reportedly receive a generous 50% commission on each device sold, a compensation model that Ashley finds unusual, as influencer marketing typically caps at around 15%. This high commission rate suggests a focus on network building rather than solely financial gain.

The Superbox is merely one brand within a crowded market of no-name Android-based TV boxes. While these devices often deliver on their promise of "free" streaming content, they frequently come pre-loaded with malware or necessitate the installation of third-party apps that ensnare the user’s internet connection in schemes for advertising fraud. In July 2025, Google filed a "John Doe" lawsuit against 25 unidentified defendants, collectively dubbed the "BadBox 2.0 Enterprise." Google alleged this botnet comprised over ten million Android streaming devices engaged in advertising fraud. The BadBox 2.0 botnet, which compromises devices before purchase and through the download of malicious apps from unofficial marketplaces, is a significant concern.

Alarmingly, several Android streaming devices flagged in Google’s lawsuit, such as the X88Pro 10 and T95 models, remain available for purchase on major U.S. retail sites like Amazon. This situation follows a June 2025 advisory from the FBI, which warned that cybercriminals were gaining unauthorized access to home networks by either pre-installing malicious software or infecting devices during the setup process through required application downloads containing backdoors. The FBI stated, "Once these compromised IoT devices are connected to home networks, the infected devices are susceptible to becoming part of the BADBOX 2.0 botnet and residential proxy services known to be used for malicious activity." The FBI identified BadBox 2.0 after the disruption of the original BadBox campaign in 2024, which primarily consisted of Android devices compromised with backdoor malware before purchase.

Riley Kilmer, founder of Spur, a company that tracks residential proxy networks, revealed that BadBox 2.0 served as a distribution platform for IPidea, a China-based entity that has become the world’s largest residential proxy network. Kilmer and others suggest that IPidea is a rebranding of 911S5 Proxy, a China-based proxy provider previously sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury for operating a botnet that facilitated billions of dollars in fraud. Proxy detection service Synthient reports that a significant portion of IPidea’s traffic is linked to ad fraud and credential stuffing attempts.

While companies like Grass may truthfully state that some of their customers are engaged in web scraping for AI training, Kilmer notes that much of this content scraping leverages proxy networks to obscure aggressive data collection. By routing this traffic through residential IP addresses, content scraping firms can make it more difficult to filter out. "Web crawling and scraping has always been a thing, but AI made it like a commodity, data that had to be collected," Kilmer explained. "Everybody wanted to monetize their own data pots, and how they monetize that is different across the board."

The appeal of devices like Superbox is growing as popular network television shows and sporting events increasingly migrate to subscription streaming services, leading consumers to realize they are spending as much, if not more, on these services than they previously did on cable or satellite TV. These streaming devices from obscure technology vendors serve as a stark reminder of the adage, "If something is free, you are the product." Even though consumers may have paid a substantial upfront cost for a device like the Superbox, it doesn’t mean the financial outlay is complete, nor does it preclude negative consequences.

While Superbox owners might argue they paid $400 for the device, the reality is that the transaction may extend beyond the initial purchase. Many Superbox customers may be indifferent to their internet connection being used to tunnel traffic for ad fraud and account takeovers, viewing it as a preferable alternative to paying for multiple streaming services. However, it’s likely that a significant number of individuals who acquire these devices, either through purchase or as gifts, have little understanding of the underlying bargain they are making when connecting them to their home routers.

Superbox employs considerable linguistic maneuvering to assert that its products do not violate copyright laws, placing sole responsibility on customers to understand and adhere to local regulations. However, U.S. consumers should be aware that using these devices for unauthorized streaming contravenes the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and can lead to legal repercussions, fines, and potential warnings or service suspensions from their Internet Service Provider.

The FBI has outlined several indicators that a streaming device may be malicious:

- The presence of suspicious marketplaces for app downloads.

- Requirements to disable Google Play Protect settings.

- Generic TV streaming devices advertised as "unlocked" or capable of accessing free content.

- IoT devices advertised from unrecognizable brands.

- Android devices that are not Play Protect certified.

- Unexplained or suspicious internet traffic.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation offers a more detailed explanation of these potential symptoms.