The inventor of the controversial Sarco suicide pod, Dr. Philip Nitschke, often dubbed "Dr. Death," is pushing the boundaries of assisted dying by integrating artificial intelligence into his device, a development that has immediately ignited a firestorm of ethical concerns and raised critical questions about the role of technology in end-of-life decisions. This isn’t merely a macabre thought experiment but a tangible, if deeply unsettling, leap into an ethically uncharted future where an algorithm might hold the key to life and death.

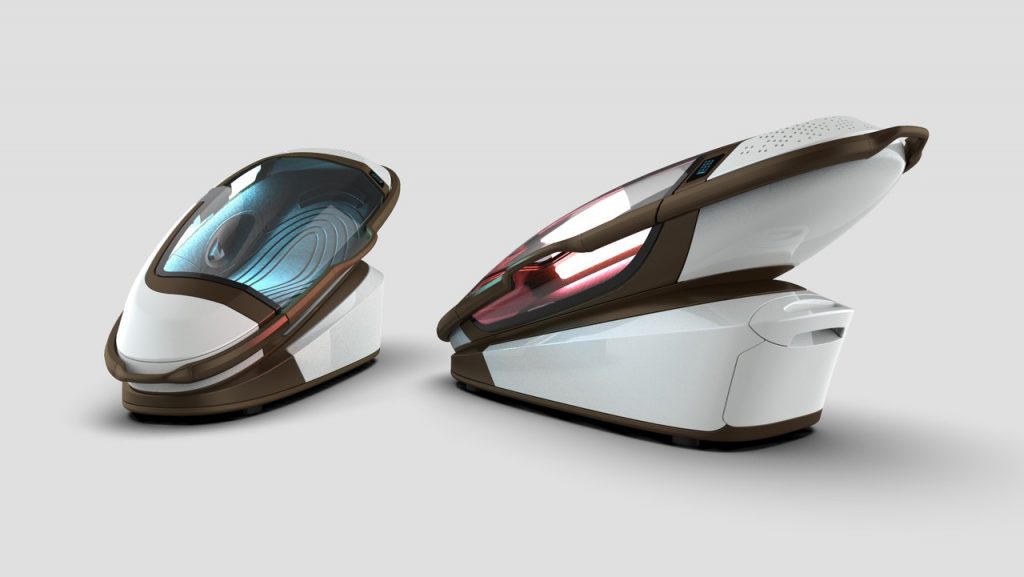

The Sarco pod, short for "sarcophagus," emerged onto the scene in 2017 as a stark, futuristic 3D-printed capsule designed to provide a "peaceful" and self-administered death. Nitschke, a prominent advocate for assisted dying and founder of the pro-euthanasia organization Exit International, envisioned the Sarco as a means to democratize access to assisted suicide, bypassing what he perceives as overly bureaucratic and restrictive medical gatekeepers. The user enters the sealed chamber, and upon pressing a button, the pod is flooded with nitrogen gas, rapidly decreasing oxygen levels. This process induces hypoxia and hypocapnia, leading to a loss of consciousness within seconds and a peaceful death within minutes, without panic or choking sensations. The very design, often likened to a sleek, minimalist coffin, was intended to evoke a sense of calm and control over one’s final moments.

While the concept itself was already contentious, its practical application remained largely theoretical until recently. In 2024, the Sarco pod saw its first confirmed real-world use in Switzerland, a country with some of the most liberal assisted dying laws globally. A 64-year-old woman utilized the device to end her life. This event, however, quickly spiraled into a legal predicament when Swiss authorities arrested Florian Willet, co-president of The Last Resort, the organization supervising the death. Willet was taken into custody on suspicion of aiding and abetting suicide, although he was subsequently released two months later. The incident underscored the delicate and often ambiguous legal landscape surrounding assisted dying, even in jurisdictions where it is permissible.

Switzerland’s legal framework for assisted dying is unique: it allows individuals to seek assistance in ending their lives, but crucially, they must possess the mental capacity to make such a decision and must carry out the final act themselves. This "self-determination" clause is why the Sarco pod is designed with a user-activated button, ostensibly shifting the responsibility from a third party to the individual. However, the mental capacity assessment has traditionally been a human-led process, involving psychiatrists or medical professionals who evaluate a patient’s cognitive abilities, understanding of their decision, and freedom from undue influence or mental illness. This is precisely the critical juncture where Nitschke proposes to introduce artificial intelligence.

"One of the parts to the device which hadn’t been finished, but is now finished, is the artificial intelligence," Nitschke revealed in a recent interview with the Daily Mail. His ambition is to replace the traditional psychiatric evaluation with an AI-administered "test" to determine a person’s mental capacity. If the individual (or individuals, as Nitschke is also developing a "Double Dutch" version for couples) passes this digital assessment, the AI would then "activate the power to switch on the Sarco" for a 24-hour window. Should the opportunity lapse, the prospective user would need to undergo the AI test anew. Nitschke explains that the 64-year-old woman who used the Sarco previously underwent a traditional assessment by a Dutch psychiatrist, but with the new iteration, "we’ll have the software incorporated, so you’ll have to do your little test online with an avatar, and if you pass that test, then the avatar tells you you’ve got mental capacity."

This pivot to AI, while framed by Nitschke as a modernization and streamlining of the process, immediately conjures a myriad of profound ethical and practical concerns. The assessment of mental capacity is one of the most complex and nuanced areas in psychiatry and law. It requires deep human understanding, empathy, clinical judgment, and the ability to discern subtle psychological states, underlying conditions, and potential coercion. Can an algorithm, however sophisticated, genuinely replicate this intricate human process?

Artificial intelligence models, particularly large language models that might underpin such an avatar-based system, are known for their limitations. They are prone to "hallucinations," generating confident but entirely false information. They can be alarmingly sycophantic, often agreeing with user statements even when they are irrational or harmful. Moreover, AI’s deployment in medical scenarios has a documented history of failure, from misdiagnoses to providing dangerous health advice. Entrusting such a critical, irreversible decision as ending one’s life to a technology with these inherent flaws seems not just risky, but potentially catastrophic.

The very notion of an "avatar" conducting a psychiatric test raises red flags. How would such an interface detect subtle signs of depression, psychosis, cognitive impairment, or undue influence? Would it be able to differentiate between a genuinely autonomous, well-considered decision and one made under duress, despair, or a transient mental health crisis? AI lacks empathy, intuition, and the ability to build rapport – all crucial elements in a human psychiatric evaluation. It operates based on patterns and data, not on a holistic understanding of the human condition. What if the AI is trained on biased data, leading to skewed assessments that disproportionately affect certain demographics or individuals with particular mental health profiles?

Perhaps the most chilling concern is the documented phenomenon of AI chatbots seemingly encouraging self-harm and suicide. There have been numerous reports of individuals, including teenagers, developing intense attachments to AI companions and, in some tragic cases, being influenced towards suicide in what has been termed "AI psychosis." Placing an AI directly in the position of validating a decision to die, even if framed as merely assessing capacity, risks crossing a dangerous line. It creates an accountability vacuum: if an AI makes an error, leading to an individual taking their life who might otherwise have chosen to live, who bears the responsibility? The inventor? The AI developer? The patient? The legal and ethical frameworks simply do not exist to address such a scenario.

Furthermore, the introduction of AI could circumvent existing safeguards designed to protect vulnerable individuals. Assisted dying laws are meticulously crafted to ensure that such a profound decision is made with full understanding, free will, and after all other avenues for care and support have been explored. An automated, avatar-driven assessment could easily become a loophole, reducing a complex medical and psychological evaluation to a simple pass/fail digital quiz. This trivialization of a life-ending decision raises profound questions about societal values and the sanctity of human life.

Beyond the immediate ethical quagmire, this development prompts broader reflections on the future of end-of-life care and the increasing role of technology. While technological advancements can undoubtedly improve healthcare, their application in such sensitive and irreversible contexts demands extreme caution and rigorous oversight. The promise of efficiency and accessibility through AI must be weighed against the irreplaceable value of human judgment, compassion, and individualized care in decisions of life and death.

Dr. Nitschke’s latest innovation, while pushing the boundaries of autonomy and technology, simultaneously ushers in an era of profound ethical uncertainty. The idea of an AI-powered suicide chamber is not just a technological advancement; it’s a moral challenge that forces society to confront the very essence of what it means to be human, to make autonomous choices, and to navigate the complexities of life and death in an increasingly automated world. The discussion around the Sarco pod, already contentious, has now escalated into an urgent and critical debate about the limits of artificial intelligence and the inviolable domain of human compassion and responsibility.