A New York City-based startup, Aircela, has unveiled a remarkable contraption capable of capturing carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere and transforming it into usable gasoline, sparking both excitement for its innovative approach to energy and skepticism regarding its current practicality and efficiency.

For decades, engineers and climate scientists have explored the audacious concept of Direct Air Capture (DAC) – a "moonshot idea" involving the active removal of excess carbon dioxide from our planet’s atmosphere to mitigate the escalating climate crisis. This ambition has garnered a diverse following, with many passionate supporters envisioning a future where atmospheric CO2 levels are actively managed, while an equal measure of skeptics raise valid concerns about the technology’s energy demands, scalability, cost-effectiveness, and potential to create a "moral hazard" by delaying more fundamental emission reductions. A central challenge for DAC has always been its energy-intensive nature and the lack of a clear, economically viable end-use for the captured CO2, often leading to it being sequestered underground – a costly and sometimes controversial process.

However, a compelling value proposition that could fundamentally shift the paradigm for carbon capture is the idea of converting the captured carbon dioxide into a different, valuable form of energy. This transformative vision treats the vast expanse of Earth’s atmosphere not merely as a repository for pollutants, but as a colossal, untapped power storage system. By extracting CO2 and synthesizing fuels, the system effectively cycles carbon, potentially offering a closed-loop or carbon-neutral energy solution, depending on the energy source used for the conversion. It is within this innovative framework that Aircela’s technology emerges, presenting a tangible, albeit nascent, example of carbon utilization that could redefine our relationship with atmospheric carbon.

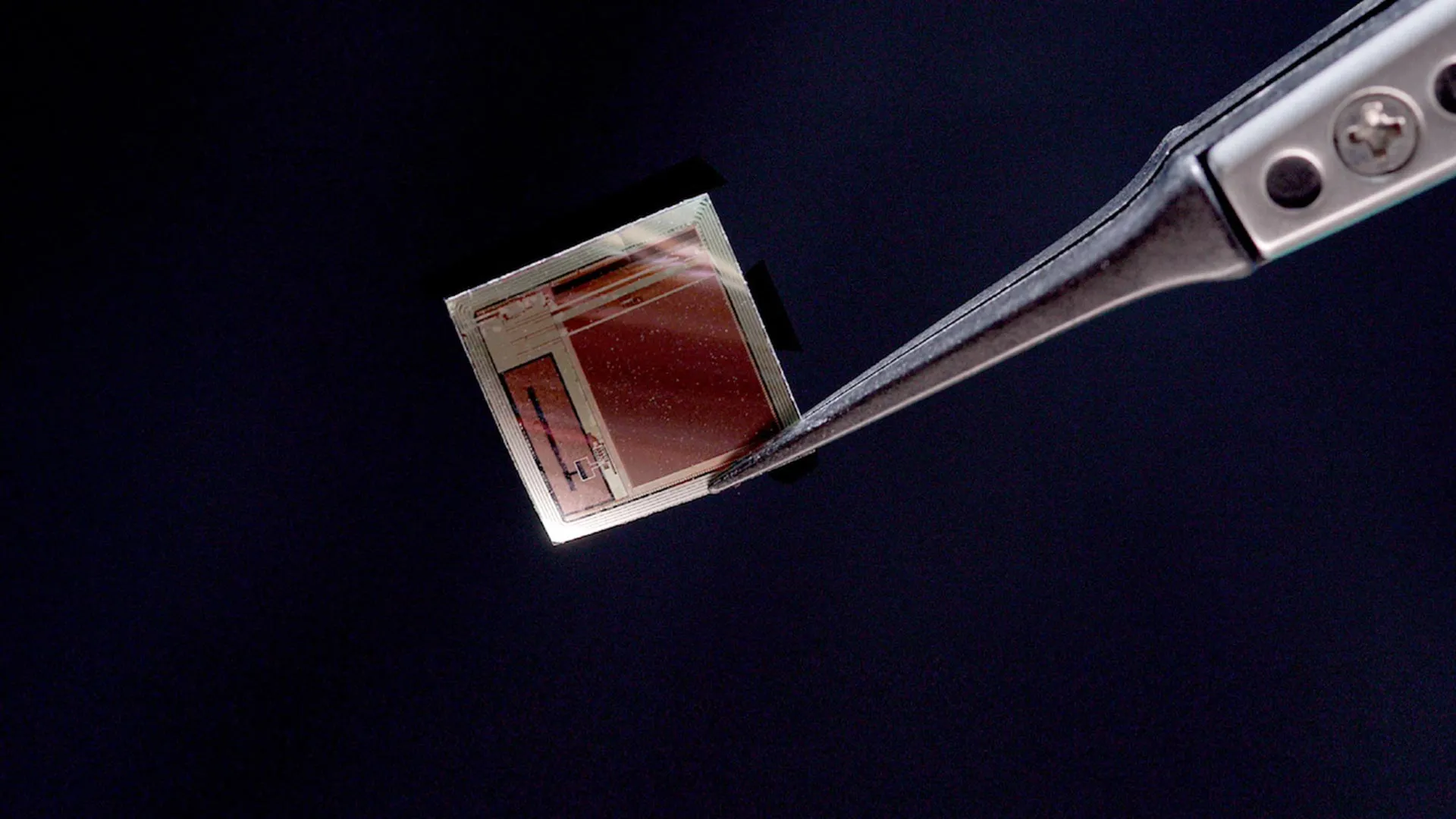

Aircela’s "intriguing contraption" is the culmination of a sophisticated, three-step scientific process, meticulously engineered to produce "fossil-free, drop-in fuel that works in existing engines, no modifications required," as the company proudly states on its website. The journey from atmospheric CO2 to liquid gasoline begins with the crucial first step: direct air capture. This phase involves separating carbon dioxide from the ambient air, a process analogous to the larger-scale DAC technologies currently under study and development by climate change-fighting scientists. While the foundational principles remain similar, Aircela’s application operates on a significantly "smaller scale," suggesting a more compact, localized approach to CO2 extraction.

Simultaneously, and integral to the entire process, the machine performs water splitting through electrolysis. This well-established electrochemical process utilizes electricity to break water (H2O) into its constituent elements: hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2). The hydrogen produced in this step is critical, serving as a primary reactant for the subsequent synthesis phase. The availability of clean hydrogen is often a bottleneck in green fuel production, making its on-site generation a key feature of Aircela’s integrated system.

With both captured carbon dioxide and freshly generated hydrogen in hand, the process moves to its second major conversion: the synthesis of methanol. In this step, CO2 and H2 are reacted together, typically under specific temperature and pressure conditions and often with the aid of a catalyst, to produce methanol (CH3OH). Methanol is a versatile chemical building block and a potential fuel in its own right, but for Aircela’s purposes, it acts as an intermediate product. The conversion of CO2 and H2 into methanol is a well-understood industrial process, demonstrating that Aircela’s innovation builds upon existing, proven chemical engineering principles.

Finally, the synthesized methanol undergoes a further conversion to become "motor-grade gasoline based on an established process." This final step likely refers to the methanol-to-gasoline (MTG) process, a technology pioneered and commercialized by companies like ExxonMobil. The MTG process uses specific catalysts to convert methanol into a mixture of hydrocarbons that are chemically identical to conventional gasoline. This ensures that the end product is indeed a "drop-in fuel," meaning it can be used directly in any internal combustion engine without the need for vehicle modifications, blending, or specialized infrastructure, thereby offering a seamless transition for existing gasoline vehicle owners.

While the scientific ingenuity behind Aircela’s system is undeniable and the promise of "gasoline from air" is captivating, the approach comes with several "serious asterisks," as highlighted by publications like Jalopnik. The primary limitation, and perhaps the most significant hurdle for widespread adoption, is the machine’s current production capacity. Aircela’s unit can only produce a single gallon of gasoline per day. To put this into perspective, a typical compact car with a 12-gallon fuel tank would require nearly two weeks of continuous operation from one of these machines to fill up. For a daily commuter, this translates to driving only a handful of miles, making it impractical for regular transportation needs.

Beyond the limited output, the process is also considerably energy-intensive, presenting a major efficiency challenge. Aircela "admitted to The Autopian last year" that the system requires "about twice as much energy going in as is trapped in the gasoline being produced." This means the end-to-end power efficiency is currently struggling to breach 50 percent, implying substantial energy losses at various conversion stages. Such inefficiency makes the economic and environmental viability highly dependent on the source of electricity. If the energy input comes from fossil fuels, the overall carbon footprint of the "air-to-gasoline" process could be equivalent to, or even worse than, simply drilling for oil and refining it. This underscores the critical necessity of powering these machines with "standalone, off-grid, photovoltaic panels," as the company suggests, or other truly renewable energy sources, to ensure the fuel is genuinely carbon-neutral or even carbon-negative.

Even with renewable energy, the operational cost remains a factor. Aircela claims that using solar panels, the electricity cost alone would be "less than $1.50 per gallon." While seemingly competitive with current pump prices, this figure excludes the substantial capital investment required for the machine itself, estimated to cost anywhere from $15,000 to $20,000 per unit, according to The Autopian. When factoring in the initial purchase price, maintenance, and the relatively low output, the true cost per gallon for a consumer could be significantly higher than conventional gasoline, at least in its current iteration.

Given these many limitations, it becomes clear that Aircela is likely targeting an extremely niche market, at least initially. The ideal prospective buyer would need to possess several specific characteristics: access to a considerable and consistent amount of affordable electricity (preferably renewable), a dependence on gasoline-based vehicles, and a context where conventional fuel supply is either expensive, unreliable, or undesirable. As one Jalopnik reader aptly argued, "Unless you’re going to use the gas in something that can’t be replaced by battery electric, like a light plane, this makes no sense. So a very niche product. A remote farm can use the extra energy from its solar panels to distill some gas on the side for the crop duster."

Indeed, the core paradox lies in the energy requirement: if an individual or entity has access to abundant, low-cost electricity, particularly from renewable sources, the more straightforward and efficient choice for personal transportation would typically be an electric vehicle (EV) that can be charged directly. The direct use of electricity to power an EV is far more energy-efficient than converting that electricity into gasoline, enduring multiple conversion losses, and then burning that gasoline in an internal combustion engine.

Therefore, the market sweet spot for Aircela’s technology might be confined to off-grid applications, remote communities, specific industrial or agricultural uses, emergency preparedness scenarios, or perhaps even for enthusiasts of classic cars or specialized machinery where electrification is not feasible or desired. It could also appeal to individuals or organizations aiming for energy independence, even if it comes at a premium in terms of efficiency and cost. The comment that "This machine would be great in ‘Mad Max,’ but in our pre-apocalyptic world, not really," humorously encapsulates the current reality: while innovative, its current iteration leans more towards a specialized tool for extreme circumstances rather than a mainstream solution for daily drivers.

Looking ahead, Aircela hopes to bring its machine to "select US markets starting in late 2026." The company’s journey will undoubtedly involve continuous research and development to improve efficiency, reduce costs, and potentially scale up production capacity. The broader context of synthetic fuels (e-fuels) is one of growing interest, particularly for sectors that are difficult to electrify, such as aviation, shipping, and heavy industry. Technologies like Aircela’s, despite their current drawbacks, represent crucial steps in exploring the potential for closed-loop carbon economies and diversifying our energy portfolio beyond fossil fuels.

Ultimately, Aircela’s air-to-gasoline machine is a fascinating testament to human ingenuity in the face of environmental challenges. It embodies the "moonshot" spirit of carbon capture, adding a tangible, if currently limited, product to the equation. While it is not the immediate answer to the global energy crisis or climate change, its existence pushes the boundaries of what’s possible, providing a glimpse into a future where the air we breathe might not only sustain life but also power our machines, albeit with significant technological and economic hurdles yet to overcome. As the "Carbon Removal Industry Is Already Lagging Behind Where It Needs to Be," every innovative approach, no matter how niche, contributes to the complex, multi-faceted quest for a sustainable future.