The global transition to renewable energy sources like solar and wind power represents a monumental leap forward in combating climate change. However, a significant hurdle persists: the inherent intermittency of these energy sources. The sun doesn’t always shine, and the wind doesn’t always blow, creating a fundamental mismatch between energy generation and demand. Storing this “green” power efficiently and affordably for use when natural conditions aren’t optimal remains one of the most pressing engineering challenges of our time. This challenge, known as long-duration energy storage (LDES), is critical for achieving a truly carbon-free electricity grid and ensuring reliable power supply around the clock.

For years, researchers and innovators have explored a myriad of creative, sometimes fantastical, concepts to bridge this energy gap. Some have envisioned massive cranes lifting and lowering colossal concrete blocks, harnessing gravitational potential energy. The idea is that excess renewable energy powers motors to lift the blocks, and when power is needed, the blocks are lowered, spinning generators. While conceptually sound, such systems often face limitations in terms of land footprint, efficiency losses, and the sheer scale required for meaningful grid-level storage.

Other proposals involve storing energy in gigantic hot rocks, effectively creating a thermal battery. Here, surplus electricity heats large volumes of rock, and this stored heat can later be used to generate steam and drive turbines. While offering high energy density, the challenges lie in material science, insulation to prevent heat loss, and the complexity of converting thermal energy back into electricity efficiently. Another intriguing concept involves repurposing abandoned oil and gas wells or deep mines by pumping water out of them. This effectively creates a closed-loop pumped-hydro storage system, where water is pumped uphill (or out of a mine) when energy is abundant, and then allowed to flow back down, turning turbines, when power is needed. While leveraging existing infrastructure, the availability of suitable sites and environmental concerns related to water usage and mine stability can be significant obstacles. Despite the ingenuity behind these ideas, none have yet proven practical, scalable, and economically viable enough for widespread deployment at the grid level.

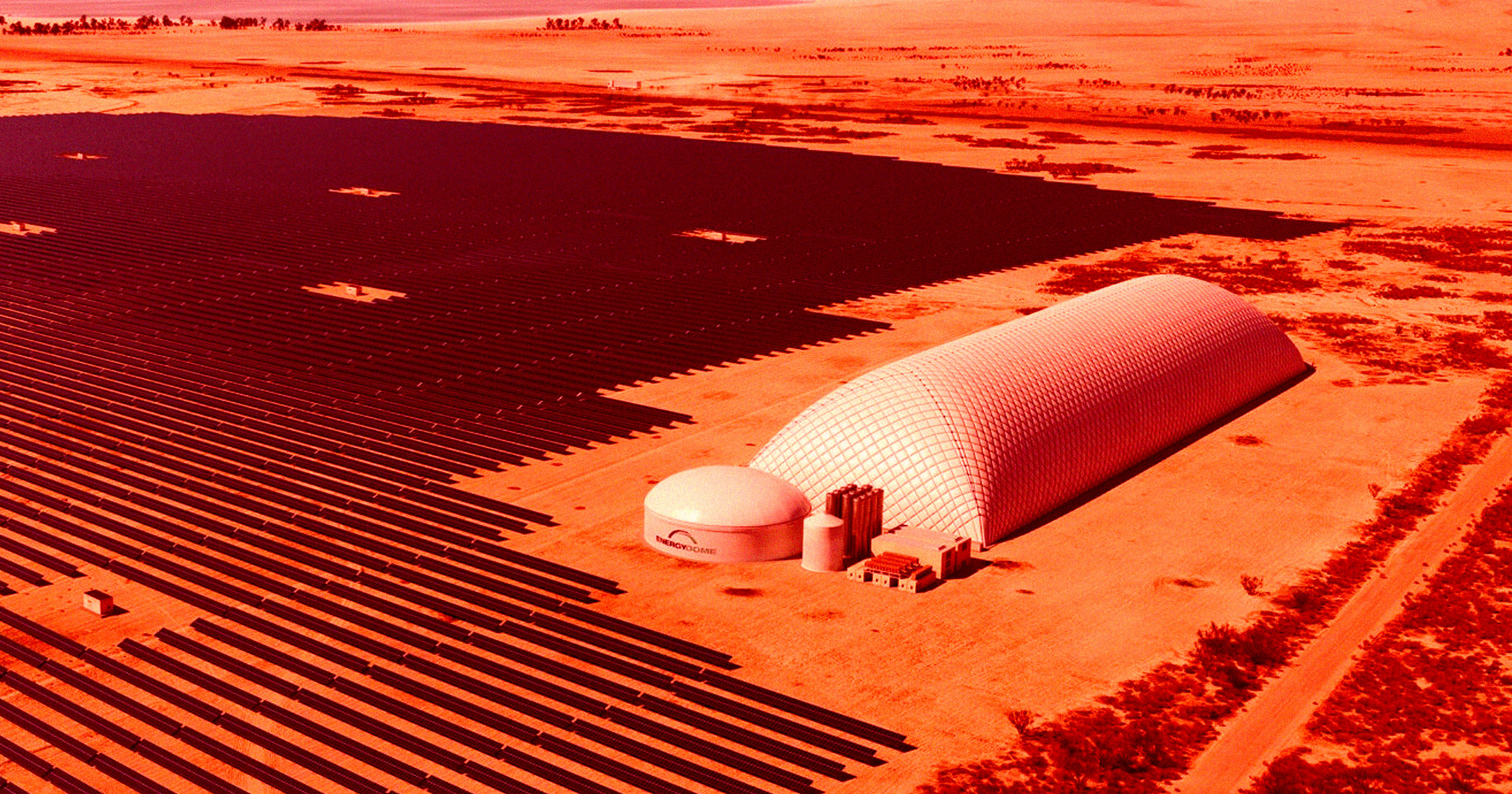

Now, a promising new player has emerged on the LDES scene. As reported by *IEEE Spectrum*, a Milan-based company named Energy Dome has introduced an intriguing approach that stores energy in enormous, self-contained domes filled with compressed carbon dioxide gas. This innovative system, dubbed the “CO2 battery,” offers a compelling solution to the intermittency problem, drawing significant attention from major tech players like Google.

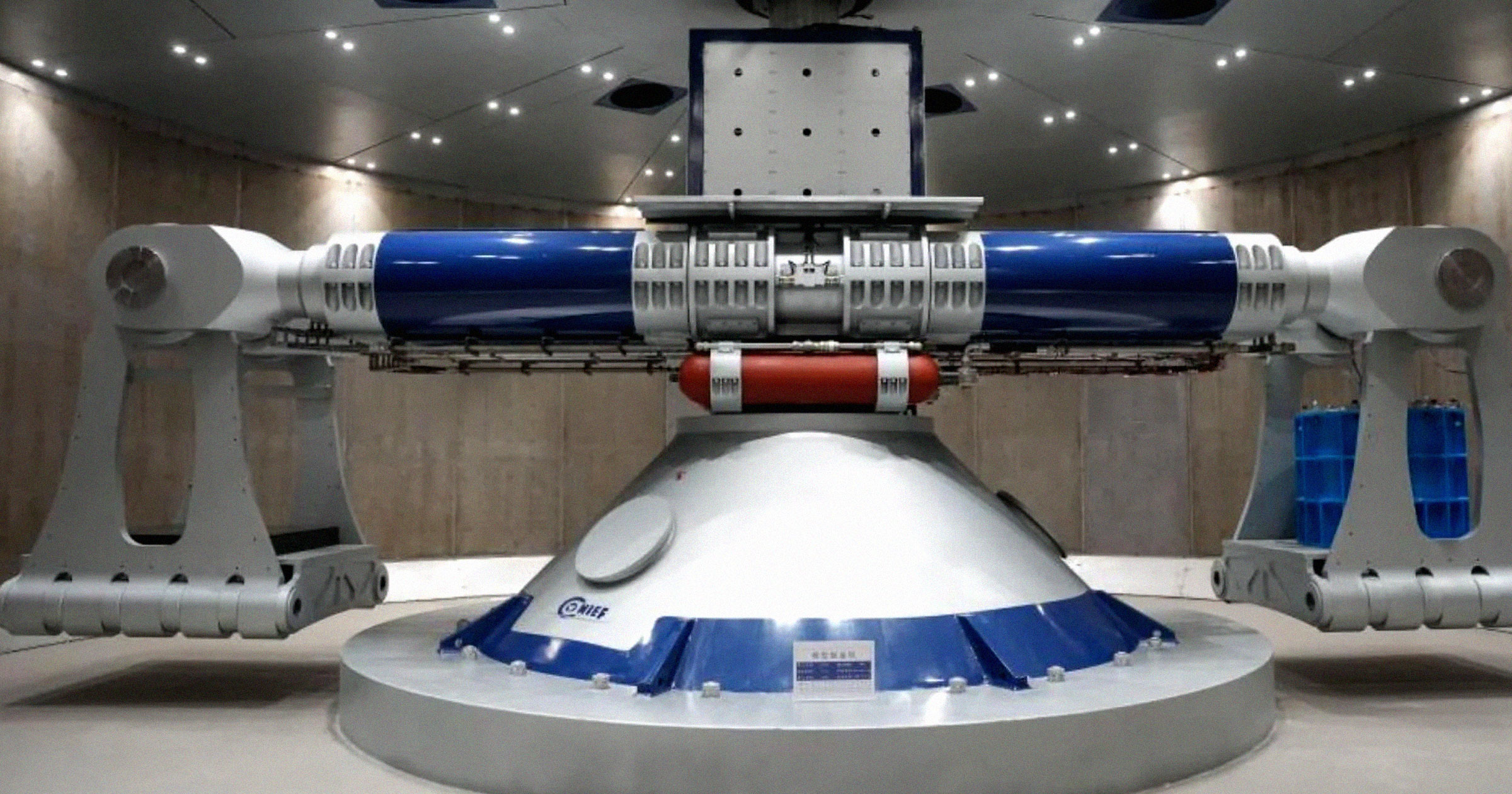

The fundamental principle behind Energy Dome’s “CO2 battery” is elegantly simple yet remarkably effective. The system operates on a closed-loop thermodynamic cycle that leverages the unique properties of carbon dioxide. When there is an excess of renewable energy available from solar farms or wind turbines, this surplus electricity is used to power compressors. These compressors take gaseous CO2 from an atmospheric-pressure gasholder (the dome) and compress it to a much higher pressure. This compression process generates heat, which is efficiently captured and stored in a thermal energy storage system. The compressed CO2 is then further cooled down to ambient temperature and condensed into a liquid state using a proprietary thermal process that utilizes the stored cold energy. Storing CO2 as a liquid allows for a significantly higher energy density in a compact volume, making the system more efficient in terms of footprint compared to storing gas alone. This “charging” phase effectively converts electrical energy into stored potential energy within the pressurized, liquid CO2. A fully charged Energy Dome facility can store a formidable 200 megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity, which is enough to power approximately 6,000 homes for a full day – a substantial capacity for grid stabilization.

When electricity is needed – for instance, during peak demand hours in the evening when solar output declines – the “CO2 battery” discharges. The liquid CO2 is evaporated and heated using the previously captured and stored thermal energy. This process converts the liquid CO2 back into a high-pressure gas. This high-pressure CO2 gas then expands, driving a large turbine that is connected to a generator, producing electricity that is fed back into the grid. The CO2 is then returned to the low-pressure gasholder, ready to begin the cycle anew. The entire process is designed for a lifespan of over 25 years, offering a durable and reliable storage solution.

The goal of this ingenious technology is to bridge the critical gap between when renewable energy is generated and when it is actually consumed. This is the essence of long-duration energy storage (LDES). For example, solar energy generation typically peaks around midday, but household electricity demand often lags hours behind, reaching its zenith in the late afternoon and evening when people return home. Without effective LDES, this surplus midday solar power might be curtailed, or fossil fuel “peaker plants” would need to fire up to meet evening demand. The CO2 battery provides a means to store that midday solar energy and dispatch it efficiently when it’s most needed.

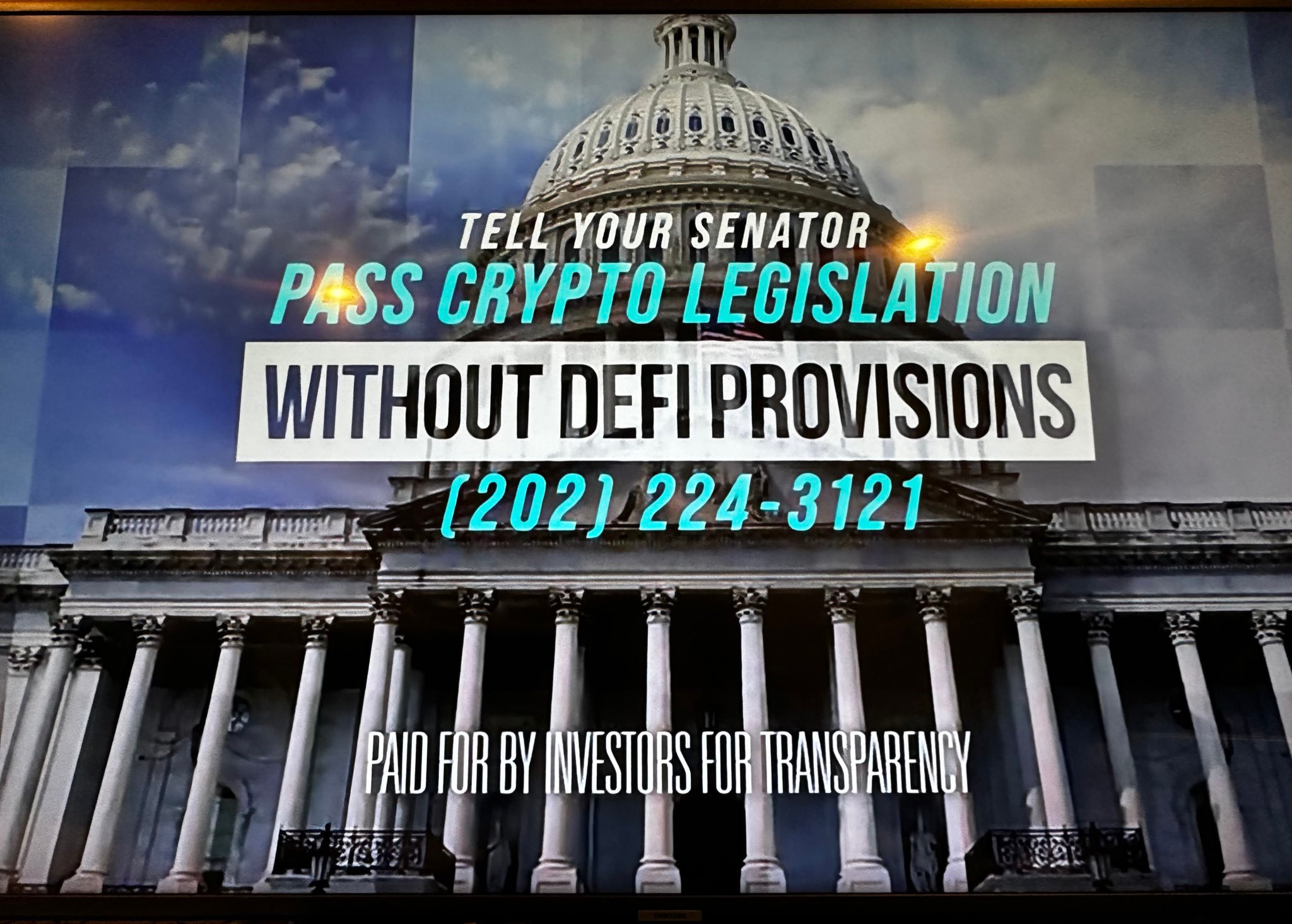

The innovative nature and promising performance of Energy Dome’s technology have not gone unnoticed by major industry players. Google, a company deeply committed to achieving 24/7 carbon-free energy across all its operations, announced a strategic partnership with Energy Dome earlier this year. This collaboration underscores Google’s proactive approach to finding scalable and sustainable energy solutions. *IEEE Spectrum* further reports that the tech giant “plans to rapidly deploy the facilities in all of its key data-center locations in Europe, the United States, and the Asia-Pacific region.” This commitment signals a significant vote of confidence in Energy Dome’s technology and its potential to revolutionize grid-scale energy storage.

Energy Dome is currently operating a pilot CO2 battery facility built on five hectares of flat land in Sardinia, Italy. This real-world testing ground allows for continuous optimization and validation of the technology. If successful, the company aims for rapid global expansion, with plans to establish similar facilities worldwide. A separate plant is already in the pipeline for Karnataka, India, a region experiencing rapid energy demand growth and increasing renewable energy integration. Additionally, authorities are actively working on laying the groundwork for another facility in Wisconsin, further demonstrating the global applicability and interest in this technology.

Ainhoa Anda, Google’s senior lead for energy strategy, highlighted a key benefit of Energy Dome’s approach: its “one-size-fits-all” nature. “We’ve been scanning the globe seeking different solutions,” Anda told *IEEE Spectrum*, adding that “standardization is really important, and this is one of the aspects that we really like” about Energy Dome. This “plug and play” capability means that the CO2 battery systems can be relatively easily deployed in diverse geographical locations without extensive customization, reducing complexity and accelerating deployment timelines. This standardization is crucial for Google, which operates data centers globally and seeks consistent, reliable, and sustainable energy solutions across its vast infrastructure. The tech giant is prioritizing deployment in areas where the electricity grid is already robust and where there is a significant surplus of renewable energy that requires storage. These strategically located CO2 batteries can then seamlessly integrate with and power nearby Google data centers, bringing the company closer to its 24/7 carbon-free energy goal.

One of the significant advantages of CO2 batteries over other renewable energy storage solutions, particularly lithium-ion batteries, lies in their material requirements. Unlike lithium-ion systems, which depend on specialized minerals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel – often sourced through complex and sometimes ethically challenged global supply chains – CO2 batteries rely on readily available industrial CO2. This significantly reduces supply chain risks, material costs, and environmental impacts associated with mining and processing rare earth minerals. Furthermore, the operational longevity and relatively low maintenance requirements of the CO2 battery system contribute to its overall economic attractiveness.

The race for effective LDES solutions is a global one, and it’s not just Google betting on CO2. According to *IEEE*, China is also actively working on constructing its own CO2 battery storage facilities, recognizing the strategic importance of this technology for its massive and rapidly expanding renewable energy infrastructure. This parallel development underscores the global recognition of CO2-based energy storage as a viable and promising pathway to grid decarbonization.

However, like any nascent technology, the CO2 battery concept is not without its considerations and challenges. Questions surrounding its long-term economic viability and environmental footprint remain areas of ongoing scrutiny. For one thing, a CO2 battery facility, particularly the large gasholder domes, requires a considerably larger physical footprint compared to a compact lithium-ion battery storage facility of equivalent capacity. This land use requirement could be a limiting factor in densely populated areas or regions with high land costs. Furthermore, while the system is designed as a closed loop, there’s an inherent risk associated with any pressurized gas storage system: the threat of a puncture or catastrophic failure. Such an event, though designed to be highly improbable, could potentially release thousands of tons of CO2 into the atmosphere.

Proponents of the technology, including Energy Dome’s CEO Claudio Spadacini, argue that the environmental benefits far outweigh these potential risks. Spadacini told *IEEE Spectrum* that any potential CO2 release from a system failure would be “negligible compared to the emissions of a coal plant” of comparable energy output. This perspective emphasizes the net positive environmental impact of displacing fossil fuel generation with stored renewable energy, even with the small residual risk. The CO2 used in the system is typically industrial-grade CO2, often sourced from existing industrial processes, effectively reusing a byproduct rather than extracting new resources.

In conclusion, Energy Dome’s CO2 battery represents a compelling and innovative step forward in the quest for scalable, long-duration energy storage. Its simple yet effective thermodynamic cycle, reliance on readily available materials, and “plug and play” design make it an attractive solution for grid stabilization and renewable energy integration. Google’s significant investment and plans for rapid global deployment underscore the technology’s potential to help achieve a 24/7 carbon-free energy future. While challenges related to land footprint and the inherent risks of gas storage exist, the promise of a reliable, standardized, and environmentally conscious LDES solution could pave the way for a more resilient and sustainable energy landscape worldwide. The journey to a fully decarbonized grid is complex, but innovations like the CO2 battery offer crucial tools to make that vision a reality.