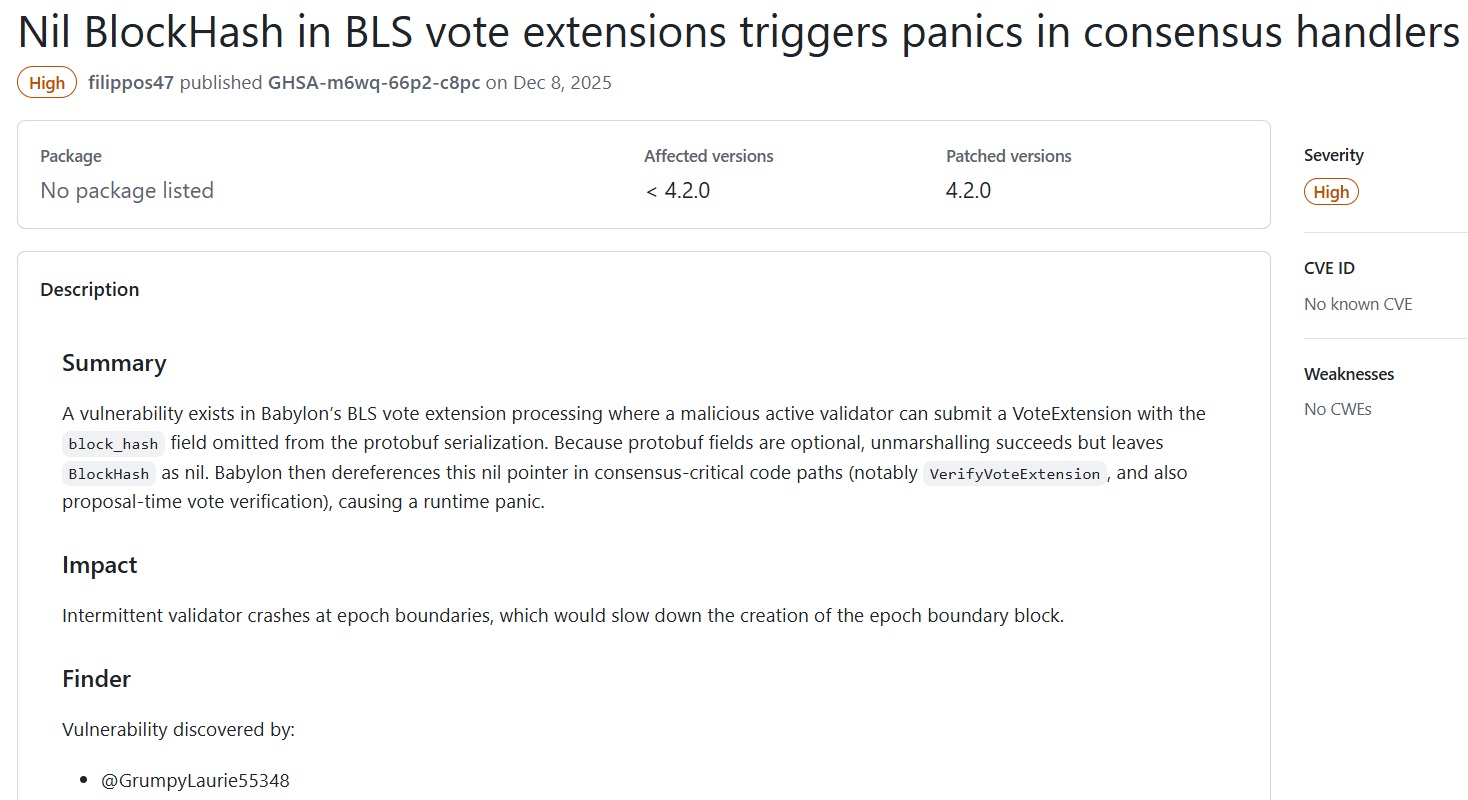

Last spring, in a stark demonstration of evolving military strategy, 3,000 British soldiers of the 4th Light Brigade, nicknamed the "Black Rats," participated in the NATO exercise Hedgehog in Estonia’s eastern forests. This deployment, a rapid response from Yorkshire via multiple transport methods, saw them join 14,000 other troops on the front line, prepared for a simulated large-scale Russian incursion. The exercise showcased some of NATO’s most formidable conventional weaponry, including 69-ton battle tanks, Apache attack helicopters, and potent truck-mounted rocket launchers. However, British Army tacticians revealed that the 4th Brigade’s most significant contribution was not a physical weapon but an invisible, automated intelligence network: Project ASGARD, a "digital targeting web."

Developed in an astonishing four months, a pace unprecedented for weapons development, ASGARD aims to create a unified wireless network connecting all "sensors" (reconnaissance assets) with all "shooters" (weapons systems). The system functions akin to an octopus, with distributed intelligence allowing for autonomous operation of its "tentacles" (individual assets) while ensuring collaborative action towards overarching objectives. During Exercise Hedgehog, reconnaissance drones equipped with advanced object recognition systems patrolled wide areas. Upon spotting a target, such as a camouflaged tank, the drone could transmit the intelligence directly to nearby weapon systems—an artillery cannon, another tank, or a ready-to-launch loitering munition drone. Soldiers operating these weapons interacted with the targeting web via Samsung smartphones. A simple selection from a dropdown menu, factoring in metrics like "probability of kill" (pKill), would initiate an almost irreversible strike course for the drone.

This exercise signals a profound shift in European defense, occurring eighty years after total war last reshaped the continent. "The Russians are knocking on the door," stated Sven Weizenegger, head of the German military’s Cyber Innovation Hub, underscoring the reliance on automated battlefield technologies for deterrence. Angelica Tikk, head of the Innovation Department at the Estonian Ministry of Defense, emphasized that "AI-enabled intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and mass-deployed drones have become decisive on the battlefield," enabling smaller nations like Estonia to "punch above our weight."

The term "mass-deployed" is crucial. Ukraine has dramatically increased its drone production, from 2.2 million in 2024 to an estimated 4.5 million in 2025. The EU’s defense commissioner, Andrius Kubilius, projects that a wider conflict with Russia would necessitate three million drones annually for Lithuania alone. Projects like ASGARD amplify these numbers by integrating the critical variable of speed. British officials claim their targeting web can reduce the kill chain—from target detection to strike decision—to under a minute, projecting a tenfold increase in army lethality within a decade. ASGARD is slated for completion by 2027, with Germany’s armed forces planning to deploy their own targeting web, Uranos KI, by 2026. The underlying theory is that a synergistic combination of lethal drones, developed rapidly by new tech firms and guided by algorithmic networks, will guarantee Europe an overwhelming victory or, ideally, create a deterrent so potent that no attack would be contemplated. Eric Slesinger, a venture capitalist specializing in defense startups, describes this as "brutal, guns-and-steel, feel-it-in-your-gut deterrence." However, an overreliance on this new military calculus carries risks. The true costs of such a war extend beyond finances, potentially transforming the very fabric of European society and its foundational project of peace, with victory far from guaranteed. Europe may be poised on a perpetual hair trigger, the consequences of which are too dire to fully comprehend.

Build It, Then Sell It

Project ASGARD involved twenty companies, from agile startups backed by venture capital to established defense giants like General Dynamics. Among these, Helsing has emerged as a key player, contributing both drones and AI capabilities. Founded in 2021 by a diverse team and bolstered by an initial €100 million investment from Spotify CEO Daniel Ek, Helsing has rapidly ascended within Europe’s burgeoning defense tech sector. The Munich-based company, with a significant presence in major European capitals and a roster of former government and military officials, achieved a $12 billion valuation last June following substantial government contracts and funding rounds. It is now Europe’s most valuable defense startup, poised to be at the forefront of any escalation in regional tensions.

Initially focused on military software, Helsing has expanded its offerings to include physical assets like AI-assisted missile drones and autonomous fighter jets. This shift reflects a growing European demand, spurred by the European Commission’s call in March 2025 for a "once-in-a-generation surge in European defence investment," identifying drones and AI as top priorities for a new initiative unlocking nearly a trillion dollars for weapons over the coming years. Germany alone has allocated nearly $12 billion to bolster its drone arsenal.

Antoine Bordes, Helsing’s chief scientist, explains the company’s operational model: "You raise money, you create technology using this money that you raised, and then you go to market with that." This approach, he notes, is driven by a "more traditional tech-startup muscle." European governments have shown receptiveness to this model, advocating for agile contracting processes that facilitate swift procurement of innovative ideas.

Helsing’s vision for European defense encompasses a multi-domain operational capability, from land and sea to air and space. In the upper echelons of their proposed battlefield, a constellation of reconnaissance satellites, developed in collaboration with Loft Orbital, would be tasked with "detect, identify and classify military assets worldwide." Lower down, their HF-1 and HX-2 loitering munition drones, capable of prolonged surveillance before engaging targets, are already seeing deployment. The company has publicly disclosed orders for approximately 10,000 airframes for Ukraine, with reports indicating successful missions in dozens of engagements. At sea, Helsing envisions autonomous mini-submarines capable of operating at depths of 3,000 feet for up to 90 days, providing persistent maritime surveillance.

Their newest offering, the Europa, is a four-and-a-half-ton, pilotless fighter jet. Designed for mass production, it is intended to penetrate heavily defended airspace, controlled remotely by a human pilot. Linking these diverse assets is Altra, Helsing’s "recce-strike software platform," which served as the central nervous system in the ASGARD trials. General Richard Barrons, former commander of the UK’s Joint Forces Command, highlights the strategic impact of such "targeting webs," envisioning scenarios where a potential Russian incursion into Estonia would be met with immediate and overwhelming destruction. Helsing’s Altra platform is designed for "saturation attacks"—a tactic of overwhelming enemy defenses with synchronized strikes—with the ultimate goal of "lethality that deters effectively," as explained by Helsing VP Simon Brünjes. In essence, the aim is to present potential aggressors with the unassailable certainty of a devastating response, a concept mirrored by the US Navy’s strategy for defending Taiwan, which they term a "hellscape" of autonomous drone swarms.

The Humans in the Loop

Despite the technological advancements, the primary obstacle to realizing the full potential of these autonomous systems remains the human element. Richard Drake, head of Anduril’s European branch, a competitor also involved in ASGARD, notes that while kill chains can be fully automated, "there is a human in the loop making those final decisions." This is mandated by current government regulations, with Estonia’s Tikk affirming that "human control is maintained over decisions related to the use of lethal force." Helsing’s drones in Ukraine, for instance, employ object recognition for target identification, with human operators reviewing and approving strikes. Full autonomy is reserved for the "terminal guidance" phase, approximately half a mile from the target, a feature also present in some locally produced drones. While this "last mile" autonomy reportedly achieves a hit rate of around 75%, the potential for misidentification, especially in complex environments, remains a concern.

Although current implementations do not constitute "killer robots," the technical barriers to full lethal autonomy are diminishing. Helsing’s strike drones are reportedly capable of performing missions without human control, though the company maintains it does not support full autonomy. The company’s AI team is working towards enabling a single human operator to manage multiple drones simultaneously, a concept mirrored by Anduril’s development of "one-to-many" systems. In such scenarios, the human operator’s capacity to intervene in the actions of individual drones is significantly reduced, particularly when the drones are coordinating for area saturation. Helsing has stated, "We do not and will not build technology where a machine makes the final decision."

Helsing’s research into drone swarming is preemptive, anticipating future government needs. Bordes emphasizes the necessity of this development, stating, "We feel that this needs to be done, and done properly, because this is what we need." This push for autonomy is driven by advances in jamming technologies, which disrupt drone communication. Russia, for example, is reportedly upgrading its drones with enhanced autonomous target recognition and inter-drone communication capabilities, and has tested autonomous torpedoes with nuclear warhead potential. Governments acknowledge that an escalating arms race in automation could be self-defeating. UN Special Rapporteur Morris Tidball-Binz warns, "The international community is crossing a threshold which may be difficult, if not impossible, to reverse later." Yet, alternatives are scarce. Weizenegger of the German Cyber Innovation Hub argues that the absence of sufficient personnel necessitates autonomous systems for effective drone control, stating, "It’s about winning or losing. There are only these two options. There is no third option."

The Need for Speed

Helsing consistently stresses the urgency of its mission, with one executive stating at a September 2025 summit, "We don’t know when we could be attacked. Are we ready to fight tonight in the Baltics? The answer is no." The company claims its ability to rapidly develop AI agents capable of controlling fighter aircraft, as demonstrated by tests of an AI agent operating a Swedish Gripen E jet over the Baltic Sea within eight months, exemplifies "Helsing speed." The Europa combat jet drone is projected for readiness by 2029.

European governments echo this sense of urgency. "We need to fast-track," asserts Weizenegger, adding, "If we start testing in 2029, it’s probably too late." Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen announced a 50 billion kroner ($7 billion) increase in defense spending, emphasizing that "There’s only one thing that counts now, and that is speed." In response, Helsing announced plans for a network of dispersed, secret "resilience factories" across Europe to produce drones at wartime capacity. Germany is expected to finalize an order for 12,000 Helsing HX-2s to equip an armored brigade in Lithuania. The company claims its first factory can produce 1,000 drones per month, a pace that would fulfill Germany’s order within a year. However, actual production may be slower due to staffing shortages.

The scale of production required is immense. Helsing founders have suggested that 100,000 HX-2 strike drones could deter a land invasion of Europe. Germany alone, they now estimate, should maintain a stockpile of 200,000 HX-2s for the initial two months of a Russian invasion. Yet, not all experts are convinced that massed drones represent a decisive advantage. While drones account for a significant portion of combat casualties in Ukraine, "they’re not determining outcomes on the battlefield," according to Stacie Pettyjohn of the Center for a New American Security, who describes the conflict as a "Somme in the sky."

Each technological breakthrough in drone warfare is met with countermeasures. In areas with heavy jamming, fiber-optic filaments are used for drone control, prompting the development of barbed wire traps and interceptors to counter these systems. Kateryna Bondar, a former Ukrainian government advisor, cautions, "If you produce millions of drones right now, they will become obsolete in maybe a year or half a year. So it doesn’t make sense to produce them, stockpile, and wait for attack." Furthermore, the reliability of AI in real-world combat conditions is questioned. Bohdan Sas of Ukrainian drone company Buntar Aerospace finds claims of advanced AI recognition amusing, noting that testing often occurs in unrealistic, open-field scenarios. Zachary Kallenborn, a research associate at the University of Oxford, points out that Russian forces have deactivated autonomous functionalities in their drones due to AI failures in real-world conditions, raising concerns about the implications of relying on such systems for massed drone operations.

Death’s Darts

The Spanish Civil War site of Corbera serves as a poignant reminder of past horrors and a warning for the future. In 1938, the town was heavily targeted by German and Italian aircraft, a novel technology at the time, much like modern drones are today. Ukraine has become Europe’s living laboratory for this new form of warfare. Ukrainian units reportedly charge Western companies for operational data, which provides invaluable real-world insights unobtainable in testing environments.

General Richard Barrons underscores the brutal nature of warfare, stating, "We need to keep reminding ourselves that the business of war, as an aspect of the human condition, is as brutal and undesirable and feral as it always is." The data from Ukraine, however, does not fully capture the collateral damage. Drones are now responsible for more civilian casualties than any other weapon in the conflict. A UN human rights commission concluded that Russia has used drones "with the primary purpose to spread terror among the civilian population," a crime against humanity. The prospect of a European drone war raises the possibility of similar tragedies on an unprecedented scale, with tens of millions living within strike range of Russia’s border. Helsing’s Brünjes has acknowledged that while human decision-making is paramount in Ukraine, a "full-scale war with China or Russia" presents a different ethical calculus.

Barrons suggests that in a scenario like an incursion into Narva, NATO would retaliate with long-range missiles and jet drones deep into Russian territory. This strategy of deterrence, while aimed at preventing war, leaves little room for de-escalation. The current mindset, according to Richard Moyes of Article 36, a UK nonprofit focused on civilian protection, is one that "we’re not imagining off-ramps." The ruins of Corbera, resembling other war zones like Tigray, Khartoum, or Gaza—where AI targeting tools played a role in escalating destruction—underscore the devastating potential of modern warfare.

A Helsing spokesperson asserts that the company "was founded to provide democracies with technology built in Europe essential for credible deterrence, and to ensure this technology is developed in line with tight ethical standards," claiming that "ethically built autonomous systems are limiting noncombatant casualties more effectively than any previous category of weapon." However, Kallenborn expresses extreme caution regarding definitive predictions about autonomous warfare. Ultimately, every weapon, regardless of its sophistication, embodies the stark reality of "lethality." The only distinction lies in the speed and scale with which this grim outcome is realized.