The pioneering research was spearheaded by Matt Eichenfield, an incoming faculty member at the University of Colorado Boulder, in collaboration with a distinguished team of scientists from the University of Arizona and Sandia National Laboratories. Their groundbreaking findings, meticulously detailed and rigorously validated, were officially published on January 14th in the prestigious scientific journal Nature, marking a significant milestone in the field of microelectronics and wave physics.

Understanding the Pervasive Power of Surface Acoustic Waves

At the heart of this transformative new device lies the fundamental principle of surface acoustic waves, more commonly referred to by their acronym, SAWs. These remarkable waves share a conceptual similarity with conventional sound waves, exhibiting oscillatory behavior. However, their propagation is distinct: instead of traversing through the bulk of a material or through the ambient air, SAWs are confined to move exclusively along the surface of a solid medium.

The raw power of surface acoustic waves is dramatically illustrated by the immense forces unleashed during large-scale seismic events. Natural earthquakes generate colossal SAWs that propagate across the Earth’s crust, causing widespread devastation by shaking buildings and triggering catastrophic landslides. Yet, on a vastly different and meticulously controlled scale, SAWs have already become an indispensable component in a multitude of modern technological applications.

"SAWs devices are critical to the many of the world’s most important technologies," emphasized Eichenfield, who serves as the senior author of the new study and holds the esteemed Gustafson Endowed Chair in Quantum Engineering at CU Boulder. His assertion underscores the pervasive and often unseen role these waves play in our daily lives. "They’re in all modern cell phones, key fobs, garage door openers, most GPS receivers, many radar systems and more," he added, highlighting the sheer breadth of their current integration.

The Silent Symphony of SAWs Within Your Smartphone

Within the intricate circuitry of a modern smartphone, SAWs perform a crucial function as highly sophisticated and exceptionally precise filters. When a radio signal arrives from a distant cell tower, it is initially converted into minuscule mechanical vibrations. This transformation is the linchpin that allows the smartphone’s internal chips to effectively discriminate between useful signals, carrying vital information, and the pervasive interference and background noise that would otherwise degrade communication quality. Once these crucial signals have been meticulously cleaned and isolated, the mechanical vibrations are then artfully converted back into radio waves for transmission and further processing.

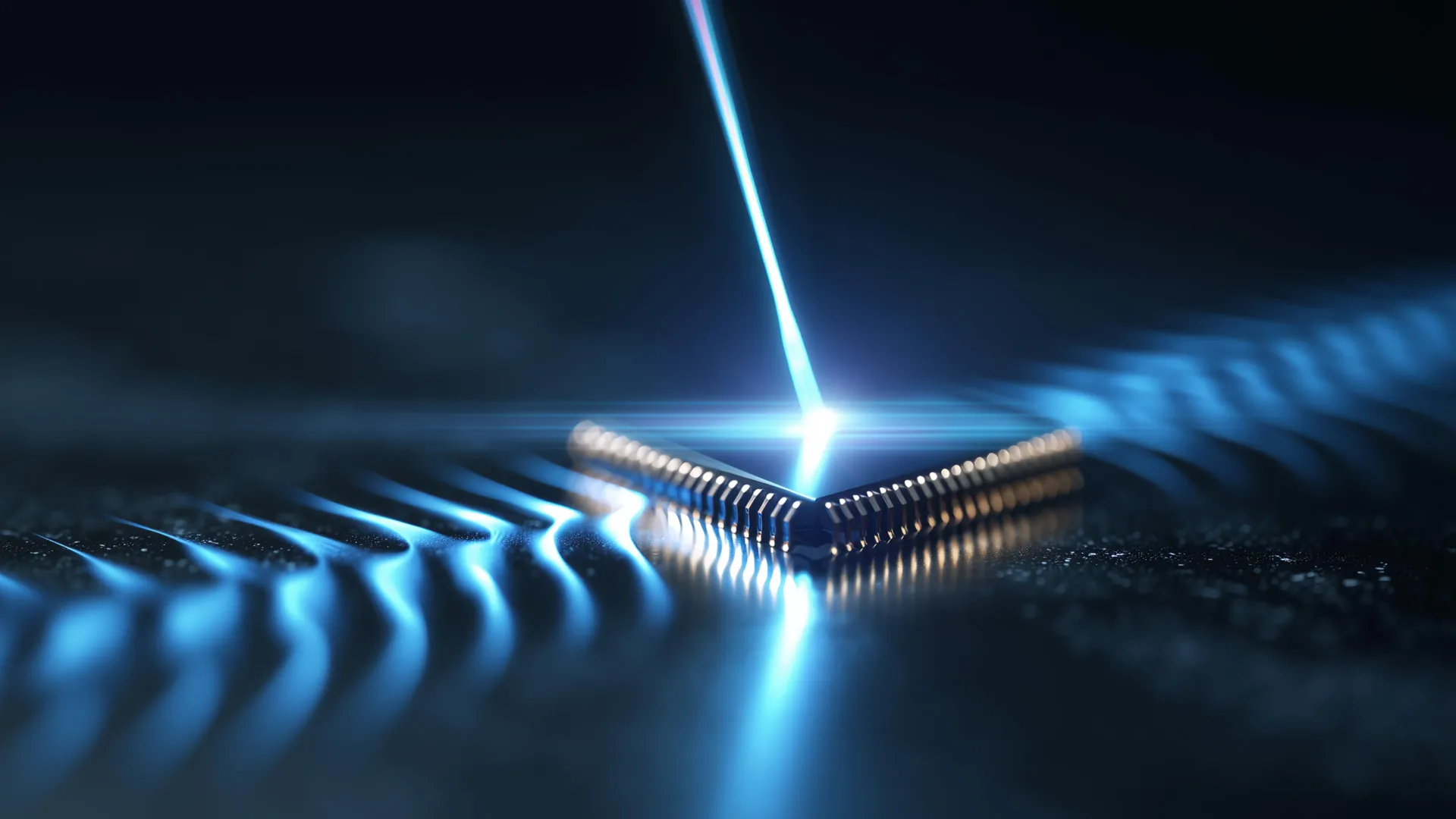

In a departure from conventional methodologies, the research team, led by Eichenfield and his esteemed colleagues, has introduced an entirely novel approach to generating these vital surface waves. They have ingeniously developed what they term a "phonon laser." Unlike a familiar laser pointer that emits a beam of light, this innovative device is designed to produce precisely controlled mechanical vibrations, essentially creating microscopic seismic events on demand.

"Think of it almost like the waves from an earthquake, only on the surface of a small chip," eloquently described Alexander Wendt, a diligent graduate student at the University of Arizona and the lead author of the study. This analogy vividly captures the essence of the technology: harnessing immense natural phenomena at an incredibly miniature scale.

A significant limitation of most existing SAW systems lies in their architectural complexity and power requirements. Typically, these systems necessitate the integration of two separate chips and a dedicated external power source to function effectively. In stark contrast, the newly developed design represents a paradigm shift, elegantly consolidating all necessary components into a single, unified chip. Furthermore, this integrated design possesses the remarkable capability to operate efficiently using only a standard battery, while simultaneously achieving substantially higher operating frequencies than its predecessors.

Crafting a Laser Designed for Vibrations: The Phonon Laser Unveiled

To fully appreciate the ingenuity behind the new phonon laser, it is instructive to first understand the fundamental principles governing conventional lasers.

Many of the lasers we encounter in everyday life are diode lasers, a ubiquitous technology that operates by generating light through a process of repeated reflection between two microscopic mirrors embedded within a semiconductor chip. As photons bounce back and forth within this resonant cavity, they interact with energized atoms, which have been excited by an electric current. These energized atoms, in turn, release additional photons, thereby amplifying the light beam and creating a coherent, intense output.

"Diode lasers are the cornerstone of most optical technologies because they can be operated with just a battery or simple voltage source, rather than needing more light to create the laser like a lot of previous kinds of lasers," explained Eichenfield, drawing a parallel to the operational simplicity of established technologies. "We wanted to make an analog of that kind of laser but for SAWs." This aspiration clearly articulates the core objective of their research: to replicate the efficiency and self-sustaining nature of optical lasers for the generation of acoustic waves.

In pursuit of this ambitious goal, the team meticulously engineered a bar-shaped device, measuring approximately half a millimeter in length – a testament to the miniaturization achieved.

A Symphony of Specialized Materials: The Architecture of the Phonon Laser

The sophisticated functionality of the phonon laser is rooted in its intricate layered structure, comprising a carefully selected stack of specialized materials, each contributing a unique property to the overall device. At the very base of this innovative architecture lies silicon, the foundational material that forms the backbone of the vast majority of modern computer chips, providing structural integrity and a familiar substrate for integration.

Positioned directly above the silicon layer is a remarkably thin film of lithium niobate, a material renowned for its potent piezoelectric properties. This means that when lithium niobate undergoes mechanical vibration, it possesses the intrinsic ability to generate oscillating electric fields. Conversely, these induced electric fields can, in turn, exert forces that stimulate further vibrations within the material, creating a synergistic feedback loop.

Capping this layered structure is an exceedingly thin sheet of indium gallium arsenide. This advanced semiconductor material exhibits exceptional electronic properties, most notably its capacity to accelerate electrons to exceptionally high velocities even when subjected to relatively weak electric fields.

In concert, these carefully chosen layers enable a direct and highly efficient interaction between the surface acoustic waves propagating along the lithium niobate surface and the fast-moving electrons within the indium gallium arsenide layer. This intimate coupling is the key to unlocking the device’s self-amplifying capabilities.

Making Waves Build Like a Laser: The Mechanism of Amplification

The researchers eloquently describe the operational mechanism of the phonon laser using an analogy to a wave pool. When an electric current is precisely applied to the indium gallium arsenide layer, it initiates the formation of surface waves within the underlying lithium niobate layer. These waves then propagate forward, encounter a carefully placed reflector, and are subsequently directed backward, mirroring the behavior of light reflecting between the mirrors in a conventional laser cavity.

Crucially, each forward pass of the acoustic wave through the active region results in a strengthening of the wave, effectively gaining energy from the interaction with the electrons. Conversely, each backward pass, while not entirely losing the gained energy, experiences a significant attenuation. "It loses almost 99% of its power when it’s moving backward, so we designed it to get a substantial amount of gain moving forward to beat that," clarified Wendt, highlighting the critical balance between gain and loss that is essential for sustained oscillation.

After undergoing numerous such forward and backward passes, the accumulated energy causes the vibrations to grow exponentially in amplitude, reaching a critical threshold where a portion of this powerful acoustic energy is intentionally allowed to escape from one side of the device. This controlled emission of amplified acoustic waves is directly analogous to how laser light eventually exits its optical cavity.

Achieving Faster Waves and Enabling Smaller Devices: The Promise of Gigahertz Frequencies

Leveraging this sophisticated amplification mechanism, the research team successfully generated surface acoustic waves vibrating at an astonishing frequency of approximately 1 gigahertz, signifying billions of oscillations per second. This remarkable achievement is just the beginning, as the researchers express strong confidence that the fundamental design principles could be further optimized to achieve frequencies in the tens or even hundreds of gigahertz.

In comparison, traditional SAW devices typically operate at frequencies that cap out at around 4 gigahertz, making the new phonon laser system a significant leap forward in terms of speed and performance. Eichenfield elaborated on the profound implications of this advance, stating that it could directly translate into the development of wireless devices that are not only dramatically smaller in physical size but also possess significantly enhanced processing power and operate with vastly improved energy efficiency.

The current generation of smartphones relies on a complex and somewhat inefficient process where multiple distinct chips are engaged in the repetitive conversion of radio waves into SAWs and then back again, a cycle that occurs every time a user sends a message, makes a call, or browses the internet. The ultimate aspiration of the researchers is to streamline this entire process by enabling the creation of a single, integrated chip capable of handling all necessary signal processing functions using the inherent capabilities of surface acoustic waves.

"This phonon laser was the last domino standing that we needed to knock down," Eichenfield declared with evident satisfaction, underscoring the pivotal nature of their discovery. "Now we can literally make every component that you need for a radio on one chip using the same kind of technology." This final statement encapsulates the transformative potential of the phonon laser, promising a future where complex wireless functionality is consolidated onto a single, highly efficient, and incredibly small microchip, ushering in a new era of miniaturized and powerful electronic devices.