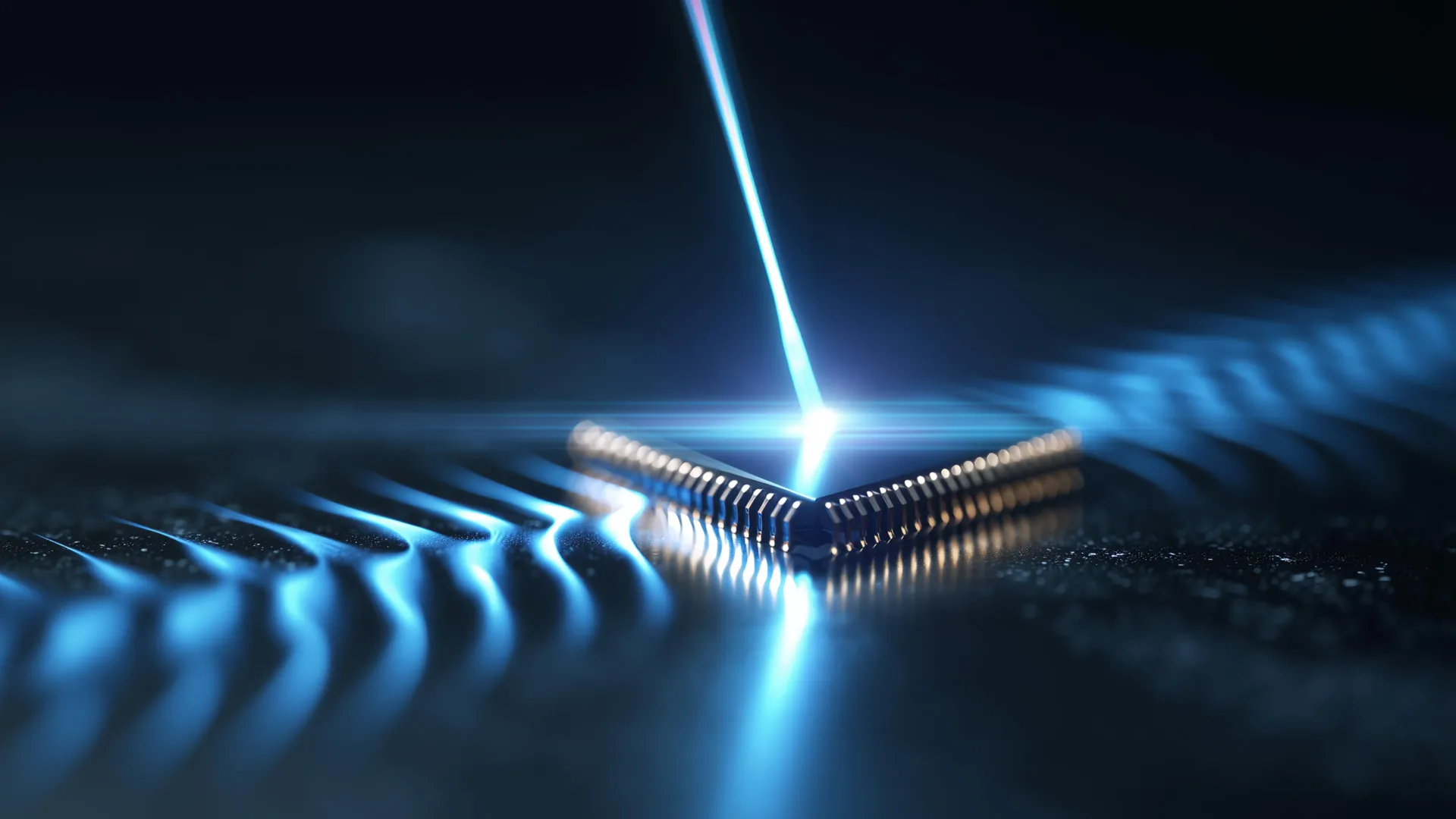

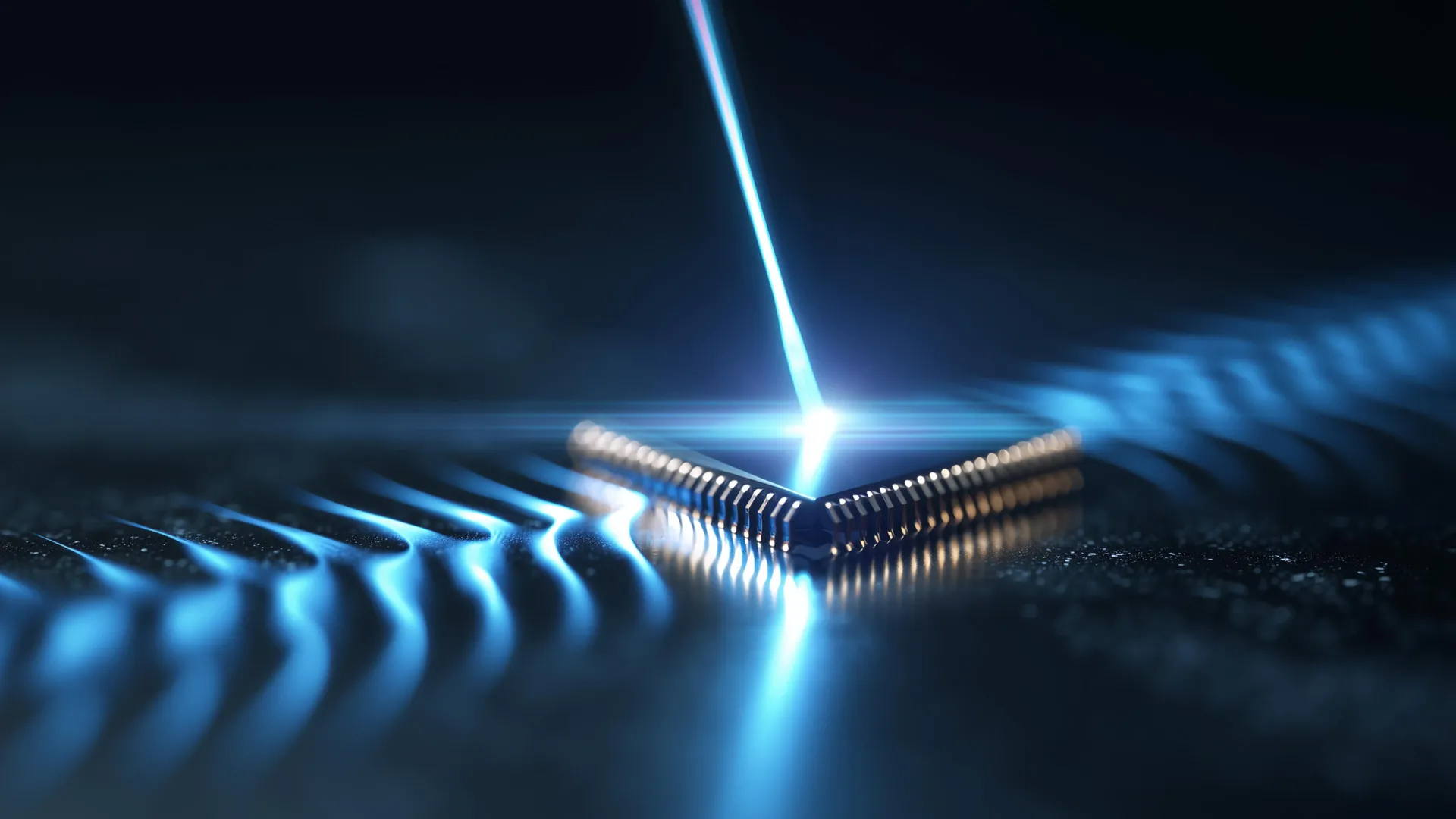

In a groundbreaking leap that echoes the tremors of miniature earthquakes on a microchip, engineers have unveiled a novel device capable of generating and controlling surface acoustic waves (SAWs) with unprecedented precision. This breakthrough centers on a device they’ve dubbed a "surface acoustic wave phonon laser," a technology poised to revolutionize the internal architecture of our digital lives, promising smaller, faster, and significantly more energy-efficient chips for smartphones and a vast array of other wireless electronics. The pioneering research, a collaborative effort led by Matt Eichenfield, an incoming faculty member at the University of Colorado Boulder, alongside esteemed scientists from the University of Arizona and Sandia National Laboratories, was formally presented on January 14th in the prestigious scientific journal Nature.

At the heart of this innovation lies the intricate manipulation of surface acoustic waves, commonly abbreviated as SAWs. These waves, while conceptually similar to sound waves, possess a distinct characteristic: they are confined to the surface of a material, rather than propagating through its bulk or through a surrounding medium like air. The sheer power of SAWs is vividly demonstrated by the colossal surface acoustic waves generated by large-scale earthquakes, which can traverse vast distances across the Earth’s crust, wreaking havoc on buildings and infrastructure. However, on a far more refined and minuscule scale, SAWs are already indispensable components in many of the world’s most critical technologies. "SAW devices are critical to many of the world’s most important technologies," emphasized Eichenfield, the senior author of the study and the Gustafson Endowed Chair in Quantum Engineering at CU Boulder. "They’re in all modern cell phones, key fobs, garage door openers, most GPS receivers, many radar systems, and more."

The pervasive influence of SAWs in modern smartphones is a testament to their remarkable capabilities as highly precise filters. When a smartphone receives radio signals from a cell tower, these signals are initially transformed into minute mechanical vibrations. This conversion is crucial, enabling the device’s internal chips to meticulously distinguish valuable signals from a cacophony of interference and background noise. Once the desired signals are isolated and "cleaned" through these mechanical vibrations, they are subsequently reconverted back into radio waves for processing.

The novel approach introduced by Eichenfield and his team involves a revolutionary method for generating these surface waves, which they have termed a phonon laser. In stark contrast to the familiar light beams emitted by a typical laser pointer, this innovative device is engineered to produce controlled mechanical vibrations. "Think of it almost like the waves from an earthquake, only on the surface of a small chip," explained Alexander Wendt, a graduate student at the University of Arizona and the lead author of the study, drawing a vivid analogy to the natural phenomenon. A significant advantage of this new design lies in its potential to consolidate functionality. While most existing SAW systems necessitate the integration of two separate chips and an external power source, the new phonon laser design ingeniously combines all essential components onto a single chip. Furthermore, it holds the promise of operating efficiently on a mere battery power, while simultaneously achieving substantially higher operational frequencies.

To fully grasp the ingenuity of the phonon laser, it is beneficial to first understand the fundamental principles of conventional lasers. Many commonly encountered lasers, such as diode lasers, operate by generating light through a process of repeated reflection between two microscopic mirrors situated on a semiconductor chip. As the light bounces back and forth within this resonant cavity, it interacts with energized atoms, which are stimulated by an electric current. These energized atoms, in turn, release additional photons, thereby amplifying and strengthening the light beam. "Diode lasers are the cornerstone of most optical technologies because they can be operated with just a battery or simple voltage source, rather than needing more light to create the laser like a lot of previous kinds of lasers," Eichenfield elaborated, highlighting the practical power source advantage. "We wanted to make an analog of that kind of laser but for SAWs."

In pursuit of this ambitious goal, the research team meticulously constructed a bar-shaped device, measuring approximately half a millimeter in length. This compact structure is ingeniously fabricated from a carefully orchestrated stack of specialized materials, each contributing unique properties to the overall functionality. At its foundational layer lies silicon, the ubiquitous material that forms the bedrock of most modern computer chips. Directly above the silicon is a critically important thin layer of lithium niobate, a material renowned for its piezoelectric properties. This means that when lithium niobate is subjected to mechanical stress or vibration, it generates oscillating electric fields, and conversely, these electric fields can induce mechanical vibrations within the material itself. The uppermost layer of this sophisticated structure is an extraordinarily thin sheet of indium gallium arsenide. This semiconductor material possesses remarkable electronic characteristics, enabling its electrons to achieve exceptionally high velocities even under the influence of relatively weak electric fields. The synergistic interplay of these layered materials is what allows the surface acoustic waves propagating along the lithium niobate surface to directly interact with the high-speed electrons within the indium gallium arsenide layer.

The researchers liken the operational mechanism of this novel device to the dynamics of a wave pool. When an electric current is applied and flows through the indium gallium arsenide layer, surface waves are initiated and propagate within the underlying lithium niobate layer. These waves then travel forward, encounter a precisely positioned reflector, and are directed back toward their origin, mirroring the light reflecting between mirrors in a conventional laser. With each forward passage, the wave gains energy and amplitude, while each backward pass incurs a significant loss of power. "It loses almost 99% of its power when it’s moving backward, so we designed it to get a substantial amount of gain moving forward to beat that," stated Wendt, underscoring the critical gain mechanism. Following numerous such cycles of amplification and reflection, the vibrations grow in intensity to a sufficient degree that a portion of this amplified wave energy is emitted from one side of the device, analogous to how a laser beam eventually exits its resonant cavity.

The remarkable efficacy of this innovative approach has already been demonstrated by the generation of surface acoustic waves vibrating at an impressive frequency of approximately 1 gigahertz, which translates to billions of oscillations per second. The research team is highly optimistic that further refinements to this design could push operational frequencies into the tens or even hundreds of gigahertz. This represents a substantial leap forward from traditional SAW devices, which typically operate at a maximum frequency of around 4 gigahertz, rendering the new system significantly faster. Eichenfield elaborated on the broader implications of this advancement, stating that it holds the potential to pave the way for wireless devices that are not only smaller and more powerful but also considerably more energy-efficient. In the context of today’s smartphones, the complex process of sending and receiving data—whether through messages, calls, or internet browsing—currently involves multiple chips that repeatedly convert radio waves into SAWs and then back again. The ultimate vision of the researchers is to streamline this entire process by enabling the creation of a single, integrated chip capable of handling all signal processing functions using the elegant principles of surface acoustic waves. "This phonon laser was the last domino standing that we needed to knock down," Eichenfield declared with evident satisfaction. "Now we can literally make every component that you need for a radio on one chip using the same kind of technology."