The Thwaites Glacier, an colossal expanse of ice situated in West Antarctica, has earned the foreboding moniker "Doomsday Glacier" for a reason that sends shivers down the spines of glaciologists and climate scientists worldwide: its potential collapse could trigger a catastrophic cascade of events, leading to a profound, irreversible surge in global sea levels. This single, massive ice stream, roughly the size of Florida or Great Britain, acts as a crucial buttress for the wider West Antarctic Ice Sheet, and its accelerating retreat is a stark indicator of the planet’s warming climate and the profound implications for humanity’s future, particularly for the tens of millions inhabiting vulnerable coastal communities across the globe.

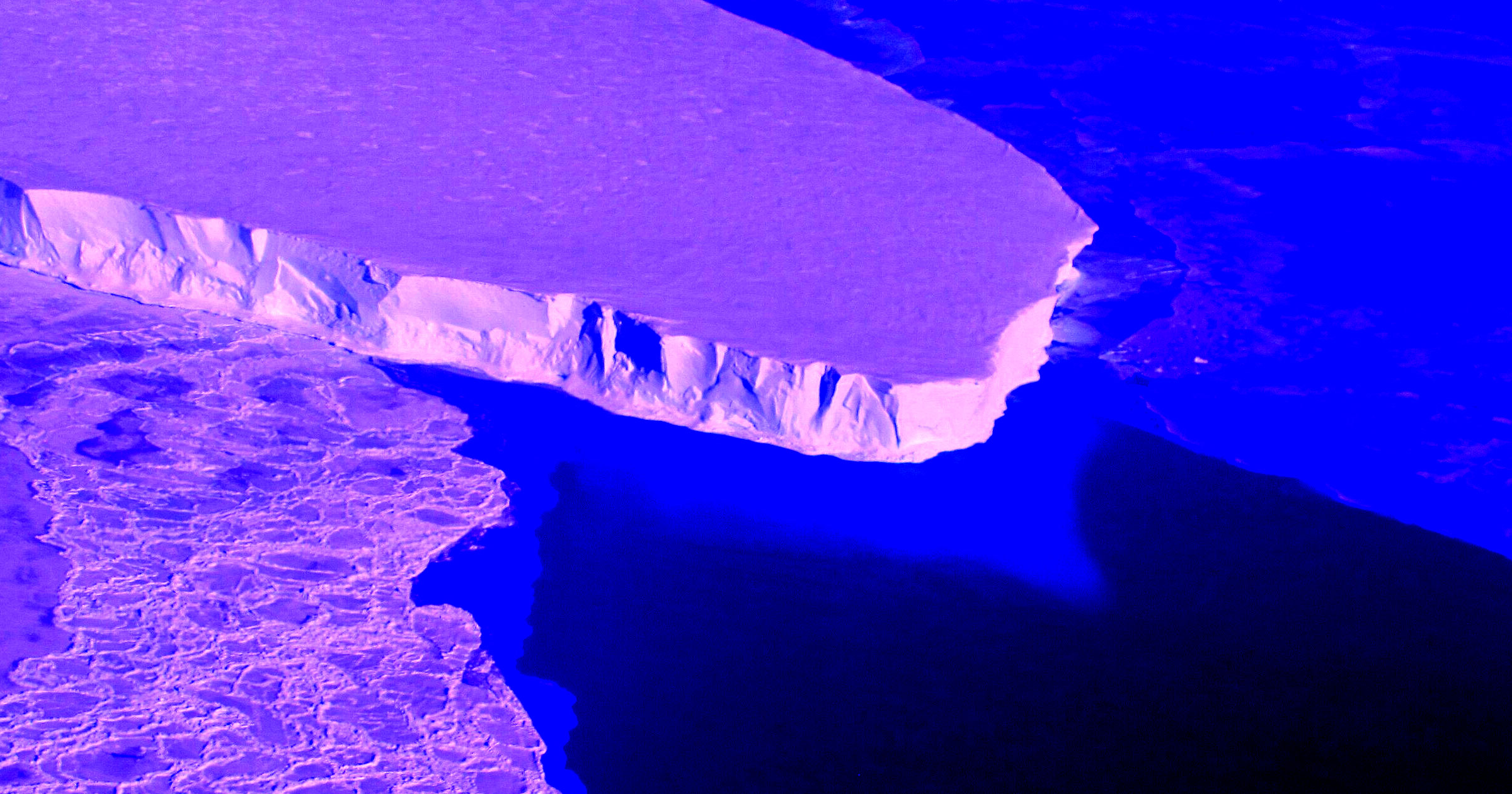

Scientists have been observing the Thwaites Glacier with a mixture of dread and intense scientific scrutiny, witnessing its retreat accelerate at an alarming pace over recent decades. New research paints an even more concerning picture, indicating that large and growing cracks are compromising its structural integrity from above, while warming ocean waters are relentlessly eroding it from below. Should this colossal ice mass — which alone holds enough ice to raise global sea levels by approximately 2 feet (65 centimeters) — collapse entirely, scientists warn it could destabilize neighboring glaciers, ultimately triggering up to an astounding 11 feet (3.3 meters) of global sea level rise. Such an event would spell certain devastation, submerging vast swathes of coastal land, displacing hundreds of millions, and reshaping geopolitical landscapes.

The vulnerability of the Thwaites Glacier stems from a geological peculiarity: much of its base rests on bedrock that slopes downwards towards the continent’s interior, a condition known as a "retrograde slope." This makes it susceptible to a process called Marine Ice Sheet Instability (MISI). As warm ocean water melts the ice from beneath, the glacier’s grounding line – the point where the ice leaves the bedrock and begins to float – retreats. On a retrograde slope, this retreat means increasingly deeper water, allowing more warm water to penetrate further inland, causing even faster melting and further retreat. This creates a terrifying positive feedback loop, a process that, once initiated, can become self-sustaining and potentially irreversible on human timescales.

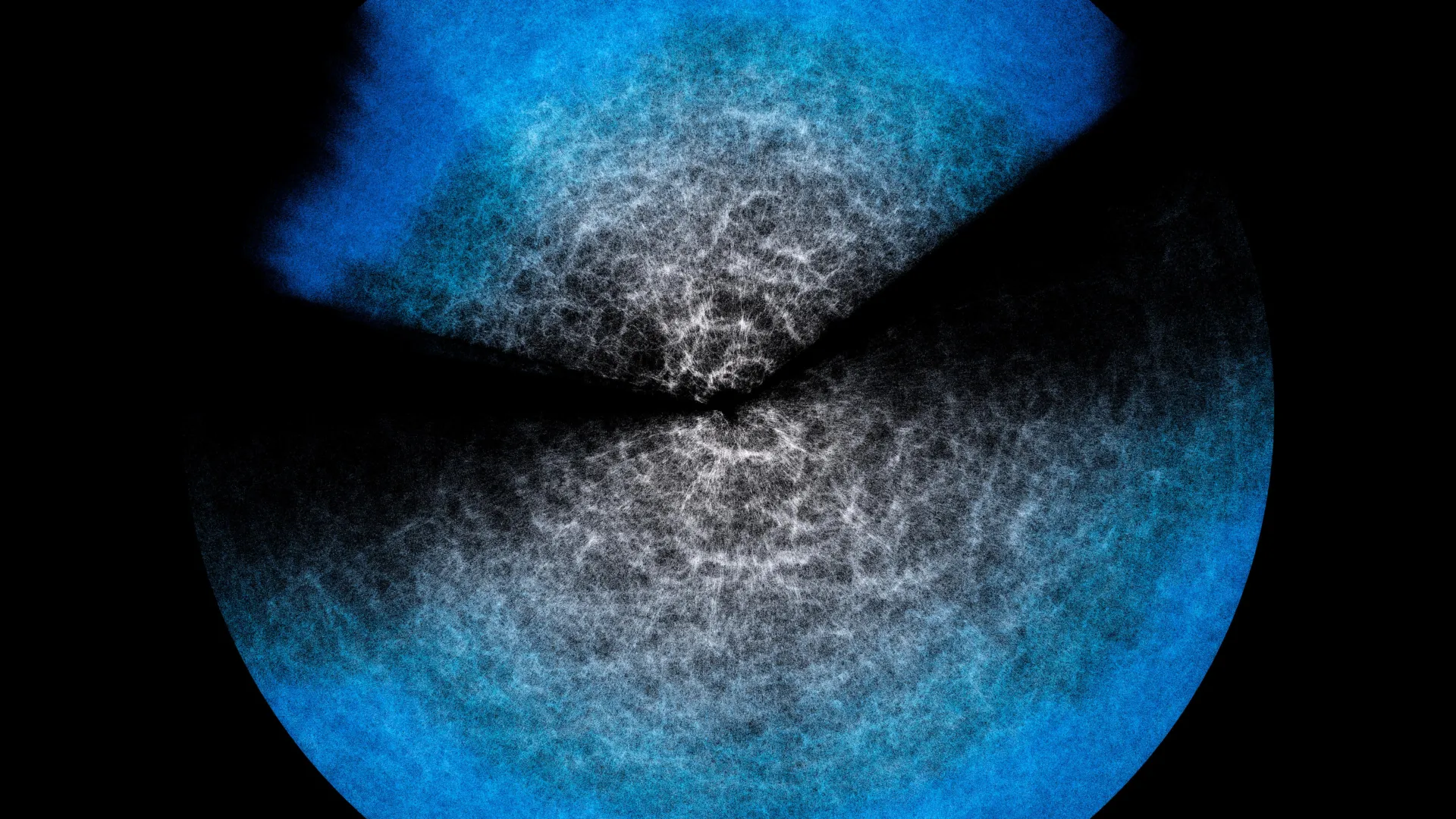

Adding to this dire prognosis, a recent study, published by the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC) and highlighted by Wired, meticulously analyzed satellite data spanning two decades, from 2002 to 2022. This research, spearheaded by a team from the University of Manitoba, revealed a troubling proliferation of fractures within the Thwaites Glacier’s ice shelf. The study observed how cracks continued to grow around a critical "shear zone" – an area of intense stress where ice flows at different speeds – located upstream of its pinning point. The pinning point is essentially a submarine mountain or ridge that helps anchor the ice shelf, providing stability.

The paper grimly states, "Over the past two decades, the shelf has experienced progressive fracturing around a prominent shear zone upstream of its pinning point, gradually compromising its structural integrity." The satellite images provided clear evidence of this accelerating deterioration. Over the two decades, the "total area length of fractures" within the ice shelf dramatically increased from approximately 100 miles to over 200 miles. However, a critical nuance in the findings was that while the total length of cracks doubled, the average length of individual fractures actually decreased. This suggests that the glacier isn’t just developing a few larger, deeper cracks, but rather experiencing a widespread proliferation of more numerous, smaller fractures. This pervasive micro-fracturing indicates a significant and widespread increase in stress across the ice shelf, making it more brittle and susceptible to rapid disintegration. The weakening of the shear zone and the compromise of the pinning point are direct threats to the glacier’s last bastions of stability.

A similarly alarming situation is unfolding beneath the ocean’s surface. Another recent study, published in Nature Geoscience, observed how warming ocean waters are relentlessly melting the Thwaites Glacier’s ice shelves. This melting is not just a slow, gradual process; it can be tracked over mere hours and days, driven by complex ocean dynamics. Swirling eddies of water, some measuring up to six miles across, are acting like powerful, underwater drills, burrowing and carving intricate channels underneath these vulnerable glaciers. These eddies, often carrying warmer, saltier "Circumpolar Deep Water" (CDW) from the open ocean, are particularly effective at transporting heat directly to the ice-ocean interface.

The international team of researchers involved in this sub-glacial study also identified a worrying positive feedback loop that significantly amplifies the melting process. As new cold, fresh water melts from the ice shelf, it mixes with the warmer, saltier ocean waters. This interaction doesn’t simply dilute the warm water; it generates intense ocean turbulence. This turbulence, in turn, enhances the transfer of heat from the ocean to the ice, causing even more ice to melt. "This positive feedback loop could gain intensity in a warming climate," explained Lia Siegelman, a coauthor of the study and an assistant professor at UC San Diego, in an interview with CNN. This discovery underscores the complexity and the potentially exponential nature of the melting mechanisms at play, suggesting that the glacier’s fate might be accelerating faster than previously understood.

The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC) represents the largest joint scientific expedition ever undertaken in Antarctica, a testament to the global concern surrounding this single glacier. Comprising hundreds of scientists from the United States, the United Kingdom, and other nations, the ITGC has been employing a vast array of cutting-edge technologies and methodologies to probe every aspect of Thwaites – from its bedrock geology and ice dynamics to oceanography and atmospheric conditions. This includes autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) mapping the seafloor beneath the ice, seismic surveys revealing the glacier’s foundational structure, boreholes drilled through miles of ice to deploy sensors, and satellite imagery providing an invaluable macroscopic view.

According to the ITGC’s 2025 report, which synthesizes years of comprehensive data, the glacier’s retreat has "accelerated considerably over the past 40 years." While the report offers a glimmer of hope by stating that "a full collapse is unlikely to occur in the next few decades," it quickly tempers this by warning that "our findings indicate it is set to retreat further, and faster, through the 21st and 22nd centuries." This nuanced projection emphasizes that while an immediate, sudden collapse might not be imminent, the long-term trajectory is unequivocally towards accelerated ice loss. The processes driving this retreat are already firmly in motion, and the glacier is marching towards an inevitable reduction in size, with significant implications for future generations.

The stakes could not be higher. An 11-foot rise in global sea levels would rewrite the world’s coastlines. Major cities like Miami, New York, London, Shanghai, and Mumbai would face partial or complete inundation. Low-lying island nations would vanish entirely. The fertile deltas of Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Egypt, home to hundreds of millions, would be submerged, leading to unprecedented refugee crises, mass displacement, and profound geopolitical instability. Infrastructure like ports, airports, and coastal power plants would be destroyed. Saltwater intrusion would contaminate freshwater sources and render vast tracts of agricultural land infertile, jeopardizing global food security. The economic cost would be in the trillions, far exceeding any current estimates for climate change adaptation.

Furthermore, the collapse of Thwaites Glacier carries the risk of triggering cascade effects across the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS). Thwaites acts as a critical choke point, buttressing the flow of ice from the vast interior of the WAIS. If Thwaites destabilizes completely, it could unleash other major glaciers like Pine Island Glacier and Pope Glacier, leading to a much larger and more rapid sea level rise than Thwaites alone could cause. This scenario represents a climate "tipping point," beyond which the process of ice sheet collapse becomes irreversible and uncontrollable, regardless of future emission reductions.

In light of these dire findings, the ITGC’s 2025 report issues a powerful call to action: "Immediate and sustained climate change mitigation (decarbonisation) offers the best hope of delaying this ice loss and avoiding initiation of similar unstable retreat in marine-based sectors of East Antarctica." This means a rapid and comprehensive global transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, massive investments in carbon capture technologies, widespread reforestation, and significant policy changes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions across all sectors of the economy. It requires unprecedented international cooperation and a fundamental shift in how societies produce and consume energy.

The scientific consensus is clear: the Thwaites Glacier is a bellwether for the broader climate crisis. While the full, catastrophic collapse may not be decades away, the processes that lead to it are already well underway. The choices humanity makes in the coming years and decades regarding greenhouse gas emissions will directly determine the speed and extent of this glacier’s retreat, and consequently, the future habitability of our planet’s coastlines. The "Doomsday Glacier" serves as a visceral, chilling reminder that the consequences of our actions are not abstract future predictions but tangible, accelerating realities that demand urgent and decisive global action. Investing in scientific understanding, mitigating emissions, and preparing for inevitable changes are not options, but necessities for the survival and well-being of future generations.