The United States’ geopolitical brinkmanship over Greenland has thrown its economic ties to the European Union into sharp relief, compelling European powers to consider what instruments they possess to combat perceived US belligerence, including the "nuclear option" of offloading trillions of dollars in US debt. This high-stakes diplomatic chess match emerged from a contentious period where US ambitions regarding Greenland, a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, reportedly escalated to the point of causing significant friction with a key transatlantic ally. While the immediate tensions appear to have cooled following a supposed "framework of a deal" struck at Davos, US designs on Greenland have, for now, been put on ice. Nevertheless, the incident has served as a stark wake-up call for EU heads of state, who remain diligently engaged in preparing possible responses to any future escalation or renewed unilateralism from Washington, underscoring a growing desire for European strategic autonomy in an increasingly unpredictable global landscape.

The initial US interest in Greenland, reportedly driven by its strategic location in the Arctic, access to valuable mineral resources, and its critical role in emerging global shipping routes, was perceived by many European leaders as an aggressive and unwelcome overture. Such moves, seen as an infringement on Danish sovereignty and a disregard for international norms, quickly ignited a debate within the EU about how to assert its collective strength against a traditional ally engaging in what some termed "economic coercion" or "geopolitical opportunism." The very notion of the US attempting to acquire a territory from a fellow NATO member state sent shockwaves through European capitals, eroding trust and highlighting the potential for Washington to act unilaterally on matters deemed vital to its national interest, even at the expense of its allies.

In the immediate aftermath of this diplomatic spat, European leaders began to publicly and privately explore a range of retaliatory measures. One prominent option discussed was the activation of the so-called "trade bazooka." This instrument, a powerful but potentially mutually destructive tool, would involve a series of coordinated economic sanctions designed to severely restrict US companies’ access to the vast and lucrative EU single market. If triggered, such measures could include punitive tariffs, non-tariff barriers, or even outright bans on specific US imports, costing American corporations billions in lost revenue and significantly disrupting global supply chains. Industries from technology and automotive to agriculture could face immense pressure, making it a potent economic weapon, albeit one with considerable collateral damage for European consumers and businesses dependent on US goods and services.

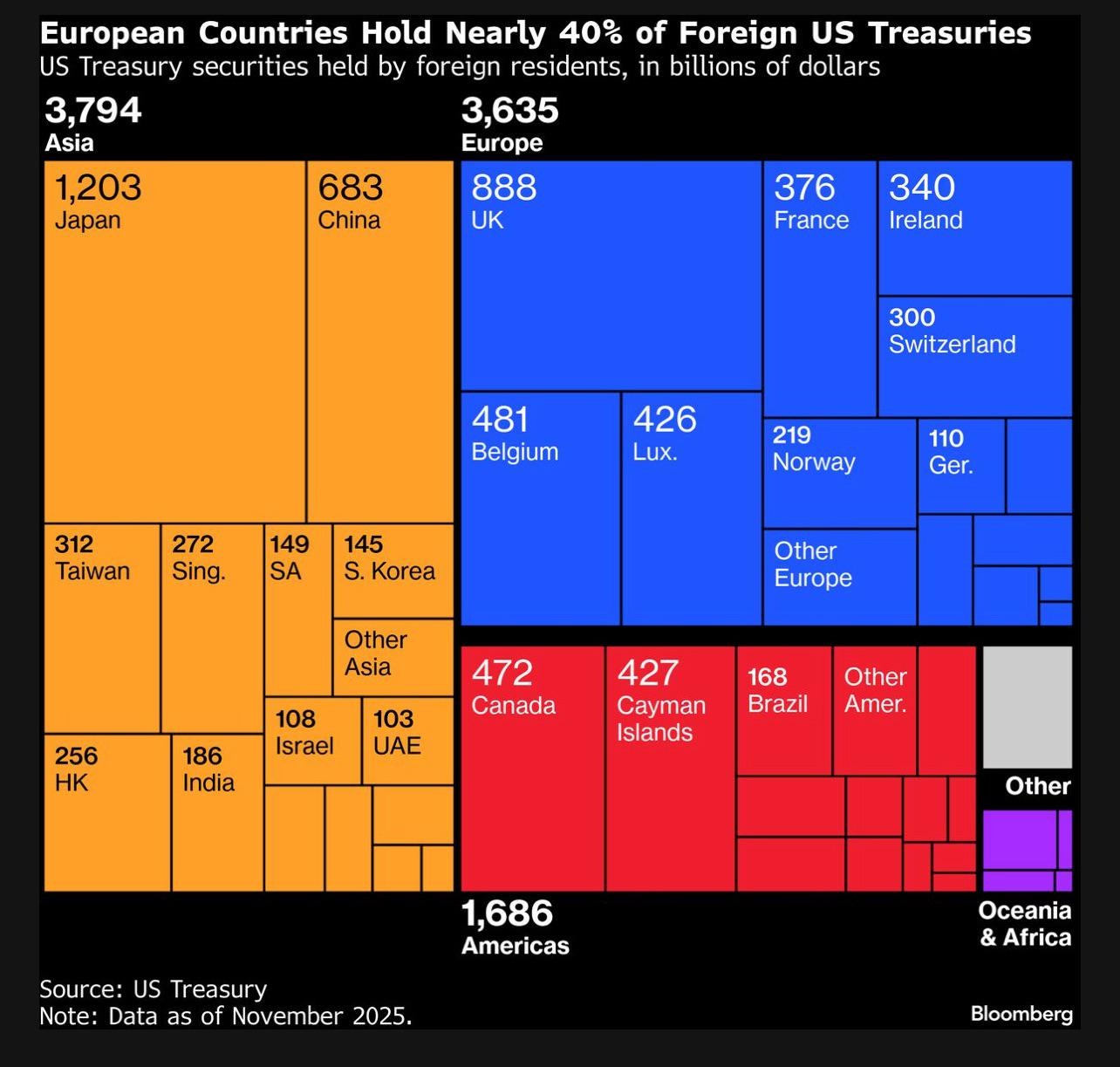

However, the more extreme and frequently labeled "nuclear option" involves the coordinated offloading of the trillions of dollars in US assets, primarily government bonds and equities, currently held in Europe. This scenario, while theoretically devastating for the US economy, also raises profound questions about its feasibility, practicality, and the potential for severe blowback on the global financial system, including Europe itself. Dumping such a massive volume of US debt could trigger a dramatic depreciation of the US dollar, spark rampant inflation within the US, and send interest rates soaring, making it prohibitively expensive for the US government to finance its existing debt and future spending. The ripple effects would undoubtedly extend globally, potentially precipitating a worldwide financial crisis as investor confidence plummets and markets become highly volatile. Furthermore, such a move could have unpredictable knock-on effects for the US financial system’s exposure to stablecoins, a rapidly growing segment of the digital asset market that increasingly relies on US Treasurys for backing.

Prior to the de-escalation marked by the Davos discussions, the atmosphere was charged with tension. While Denmark reportedly deployed special forces to Greenland as a symbolic assertion of sovereignty, other EU heads of state openly debated the merits of economic countermeasures. Among those advocating for a strong European response was former Dutch Defense Minister Dick Berlijn, who suggested that Europe could indeed wield its substantial holdings of US debt as significant leverage. Berlijn articulated a clear warning, stating, "If Europe decides to offload those bonds, it creates a big problem in the US. [The dollar] crashes, high inflation. The US voter won’t like that." His comments highlighted the political pressure such a financial move could exert on Washington, directly impacting the American public through economic hardship.

Echoing this sentiment, George Saravelos, Deutsche Bank’s chief FX strategist, underscored a fundamental vulnerability of the US economy in a widely circulated note: "For all its military and economic strength, the US has one key weakness: it relies on others to pay its bills via large external deficits." Saravelos’s analysis pointed to the substantial foreign ownership of US debt as a critical component of American financial stability. He noted that Europe collectively owns an estimated $8 trillion in US bonds and equities, a staggering sum that he claims is "twice as much as the rest of the world combined." This significant exposure gives Europe considerable theoretical leverage, making its potential actions a matter of grave concern for US policymakers.

However, the practicalities of weaponizing such a vast financial holding are fraught with immense challenges. The question of whether Europe could genuinely offload this debt is complex, involving both the logistical hurdles of compelling a sale and, critically, identifying sufficient buyers in a global economic landscape increasingly characterized by de-dollarization efforts and geopolitical realignments.

Yesha Yadav, a professor of law and associate dean at Vanderbilt University, offered a cautious perspective to Cointelegraph, explaining that "Foreign government buyers tend to be sticky, meaning that they will not easily move their holdings unless there is a serious need for them to do so." This "stickiness" refers to the tendency of central banks and sovereign wealth funds to maintain their holdings of US Treasurys due to their unparalleled liquidity, safety, and depth, making them indispensable for reserve management and global trade.

A significant hurdle is that much of the US debt held in Europe is not directly owned by governments but by private entities, including pension funds, insurance companies, banks, and other institutional investors. As Yadav noted, hedge funds in financial hubs like the UK, Luxembourg, and Belgium have emerged as major buyers of US Treasurys, attracted by their stability and liquidity. Therefore, even if European political leaders desired to initiate a debt dump, they would face the formidable task of compelling these private, commercially driven entities to sell off their holdings. Such a move would likely require unprecedented legislative or regulatory action, potentially infringing on property rights and investor freedoms, and setting a dangerous precedent for government interference in private markets. Yadav concluded that it "does not seem likely in the near term that European governments may impose restrictions on hedge funds buying US Treasurys," highlighting the immense legal and economic complexities involved. Kit Juckes, SocGen’s chief FX strategist, further emphasized this point, writing that "The situation probably needs to escalate a fair bit further before they damage their investment performance for political purposes," suggesting that private investors would prioritize returns over political objectives unless under extreme duress.

Despite these challenges, Yadav suggested that governments "may potentially think about opening up the kinds of government debt that are considered most secure as collateral." This could involve promoting European sovereign bonds (like German Bunds) as alternative "risk-free" assets, thereby gradually reducing the reliance on US Treasurys for collateral in financial transactions. However, the main problem persists: there are simply not enough alternatives to US debt that offer the same combination of "risk-free" status, deep liquidity, and sheer market size. US Treasurys remain the benchmark for safe-haven assets globally. Yadav elaborated, "Even as other highly stable and safe countries, such as Germany, begin to issue debt, their debt markets remain relatively small, such that it is very difficult to envision them ever taking the place of the US Treasury market." The scale of the US market, with its diverse range of maturities and active trading, is unmatched, making it virtually impossible for any other single sovereign debt market to absorb a mass exodus from US assets.

The issue of finding alternative buyers for such a massive volume of dumped US debt is equally challenging. China, historically one of the largest foreign holders of US Treasurys, has been steadily scaling back its purchases, driven by its own geopolitical objectives, currency diversification strategies, and trade tensions with the US. While other Asian economies do hold substantial foreign exchange reserves, their collective capacity to absorb trillions of dollars in US assets is limited. For context, the market capitalization of the MSCI All-Country Asian index, which tracks large and mid-cap stocks across developing and emerging markets in Asia, is roughly $13.5 trillion. In comparison, the FTSE World Government Bond Index is about $7.3 trillion. These figures underscore the vast disparity between the size of existing alternative markets and the immense volume of US debt that would need to be absorbed.

Analysts at Rabobank succinctly summarized the predicament: "While the US’s large current account deficit suggests that in theory there is the potential for the USD to drop should international savers stage a mass retreat from US assets, the sheer size of US capital markets suggests that such an exit may not be feasible given the limitations of alternative markets." This highlights the inherent paradox: the US relies on foreign capital, but its financial markets are so vast that a complete, sudden withdrawal would be self-defeating for those trying to exit, as it would crash the value of their remaining holdings and leave them with few viable alternatives.

An emerging and increasingly significant buyer of US debt is stablecoin issuers. The GENIUS Act, landmark US legislation creating a comprehensive framework for stablecoins, mandates that issuers operating in the country must maintain reserves predominantly backed by dollars and highly liquid US Treasurys. This regulatory requirement has transformed stablecoin issuers into substantial and growing purchasers of US government debt. As Yadav observed, "That [stablecoin issuers] are growing as fast as they are means that their need for Treasurys is correspondingly high." This trend offers a considerable advantage for US policymakers, as it creates a new, eager demand source for government debt. However, it also deepens the intricate link between the continued growth and stability of stablecoin issuers and the ongoing liquidity and popularity of US Treasury markets.

The proliferation of stablecoin issuers as major buyers of US debt, while beneficial for financing government spending, does not come without its own unique set of risks. This increasingly concentrated demand, combined with a potentially shrinking pool of traditional foreign buyers in the event of an EU debt dump or even a significant reduction in European exposure, could spell significant trouble for US Treasury markets. Yadav and Brendan Malone, formerly of the Federal Reserve Board, have previously highlighted concerning liquidity shocks in US debt markets, notably in March 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and again in April 2025. These episodes demonstrated how quickly even the most liquid market in the world can seize up under stress.

In the hypothetical, but increasingly plausible, event of a "run" on stablecoin issuers – triggered by a loss of confidence, regulatory uncertainty, or a major hack – mass redemptions could force these issuers to rapidly sell off their Treasury holdings to meet withdrawal demands. This forced selling, particularly in a market already experiencing reduced liquidity due to fewer traditional buyers, could exacerbate a lack of counterparties, preventing issuers from offloading their securities efficiently. Such a scenario would not only lead to the insolvency of stablecoin issuers but would also significantly impact the credibility and stability of US Treasury markets, potentially causing wider financial contagion.

The incident surrounding Greenland serves as a powerful microcosm of the economic and military escalation occurring in an increasingly multi-polar world, creating visible rifts between former allies. While there is still hope for constructive dialogue and resolution between the EU and the US, the underlying tensions and the exploration of such drastic economic countermeasures signal a fundamental shift in transatlantic relations. Latvian President Edgars Rinkēvičs encapsulated this precarious situation, stating, "We are not yet out of the woods […] Are we in an irreversible rift? No. But there is a clear and present danger." This danger extends beyond the sovereignty of Greenland and the stability of Europe; it now directly implicates the very foundations of US debt markets, highlighting a vulnerability that geopolitical actions can expose and exploit. The long-term implications of such considerations could reshape global finance and the international order, signaling a future where economic interdependence is increasingly weaponized in the service of national interest.