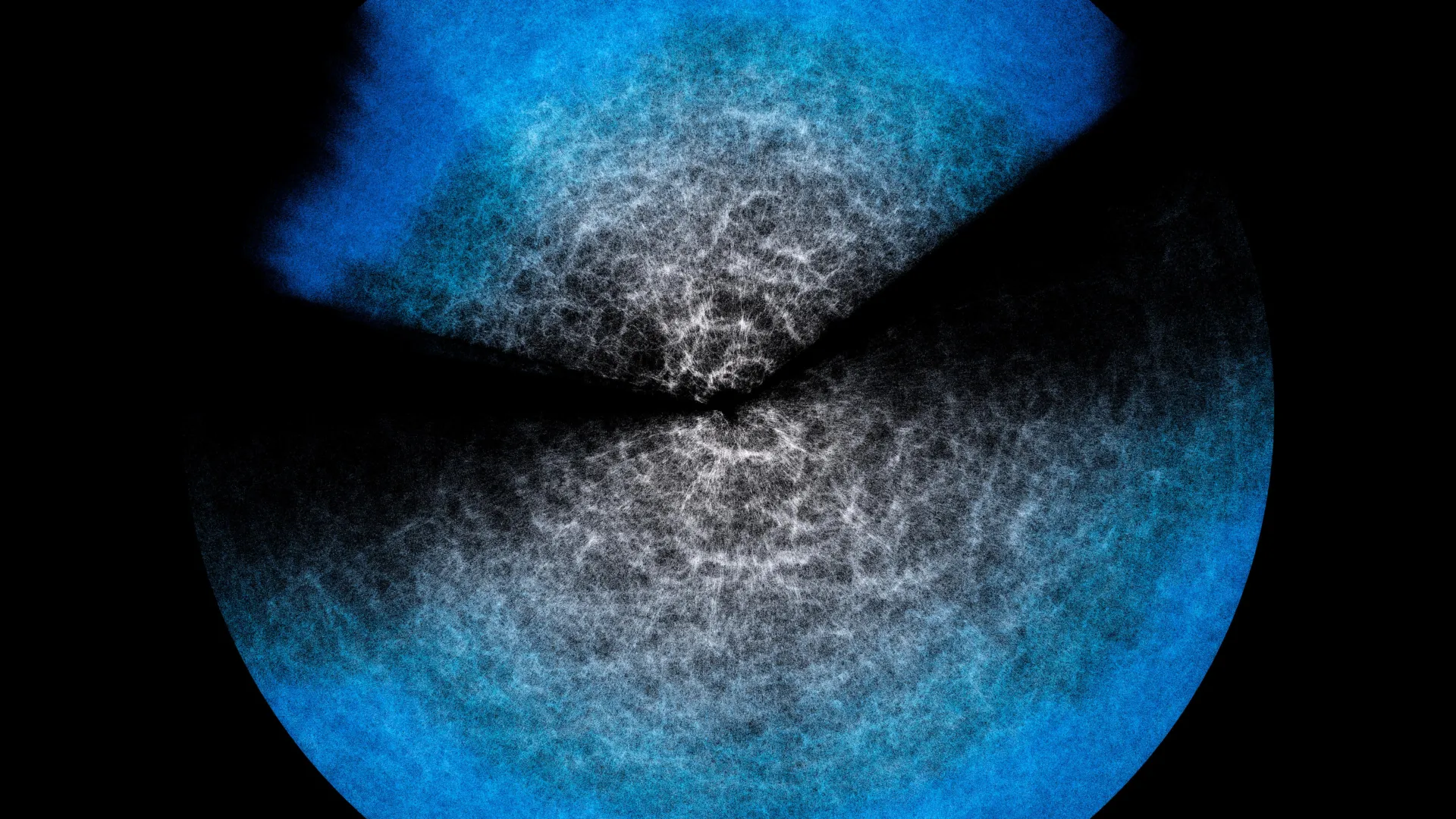

The sheer immensity of the Universe can be staggering to contemplate. Imagine the grandeur of a galaxy, a swirling metropolis of billions of stars, and then dwarf that by comparing it to the vast emptiness of the cosmos. A galaxy, in this cosmic context, shrinks to an infinitesimal point. These seemingly solitary dots, however, are not isolated. They are the building blocks of a far grander structure, a cosmic tapestry woven from countless stars and gas clouds, forming immense clusters. These clusters, in turn, are not scattered randomly but are drawn together into even larger superclusters, which then elegantly arrange themselves into a sprawling, interconnected network. This intricate, three-dimensional latticework is often described as the "cosmic web," a colossal skeleton of the Universe, characterized by vast filaments of matter threaded through immense, seemingly empty regions known as voids.

Grappling with the scale of such an entity naturally provokes a fundamental question: how can we possibly comprehend, or even "see," something so unfathomably vast? The answer, as scientists readily admit, is far from simple. It requires a sophisticated interplay of theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence. Astronomers meticulously combine the fundamental laws of physics that govern the Universe with the torrent of data collected by increasingly powerful astronomical instruments. From this fusion of knowledge, they construct theoretical models, such as the one known as EFTofLSS (Effective Field Theory of Large-Scale Structure). These models, when "fed" with observational data, are designed to statistically describe the intricate patterns of the cosmic web. By analyzing these patterns, scientists can then estimate the key parameters that define its structure and evolution.

However, the power of these detailed theoretical models, like EFTofLSS, comes at a significant cost: they are computationally demanding, requiring substantial processing time and resources. As the volume of astronomical data at our disposal continues its exponential growth – a trend driven by ever more sensitive telescopes and ambitious sky surveys – the need for more efficient analysis methods becomes paramount. Scientists are actively seeking ways to "lighten the load" of these analyses without compromising their precision. This is precisely where the concept of "emulators" emerges as a crucial innovation. Emulators are essentially sophisticated computational tools designed to "imitate" the behavior of these complex models, but with a dramatically accelerated operational speed.

The inherent question with any computational "shortcut" is the potential for a loss of accuracy. To address this critical concern, an international team of researchers, comprising esteemed institutions such as INAF (Italy), The University of Parma (Italy), and the University of Waterloo (Canada), has undertaken a rigorous study. Their findings, published in the prestigious Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (JCAP), meticulously evaluate an emulator they have developed called Effort.jl. The results are remarkably promising: Effort.jl demonstrably delivers essentially the same level of correctness as the intricate theoretical model it imitates. In some instances, it even reveals finer details that might be obscured or computationally prohibitive to extract with the original model. Crucially, Effort.jl achieves this remarkable feat by operating in mere minutes on a standard laptop, a stark contrast to the hours or days typically required on a high-performance supercomputer.

Marco Bonici, a researcher at the University of Waterloo and the lead author of the study, eloquently illustrates the concept with an analogy. "Imagine wanting to study the contents of a glass of water at the level of its microscopic components, the individual atoms, or even smaller," Bonici explains. "In theory, you can. But if we wanted to describe in detail what happens when the water moves, the explosive growth of the required calculations makes it practically impossible." He continues, "However, you can encode certain properties at the microscopic level and see their effect at the macroscopic level, namely the movement of the fluid in the glass. This is what an effective field theory does, that is, a model like EFTofLSS, where the water in my example is the Universe on very large scales and the microscopic components are small-scale physical processes."

In essence, the theoretical model statistically explains the underlying structure that gives rise to the observable data. Astronomical observations are fed into the computational code, which then generates a "prediction" of the cosmic web. However, as Bonici highlighted, this process is time-consuming and requires significant computational power. Given the sheer volume of data already accumulated from current astronomical surveys and the even greater influx expected from upcoming projects like DESI, which has already begun releasing its initial data, and the highly anticipated Euclid mission, performing this exhaustive analysis for every dataset is simply not practical.

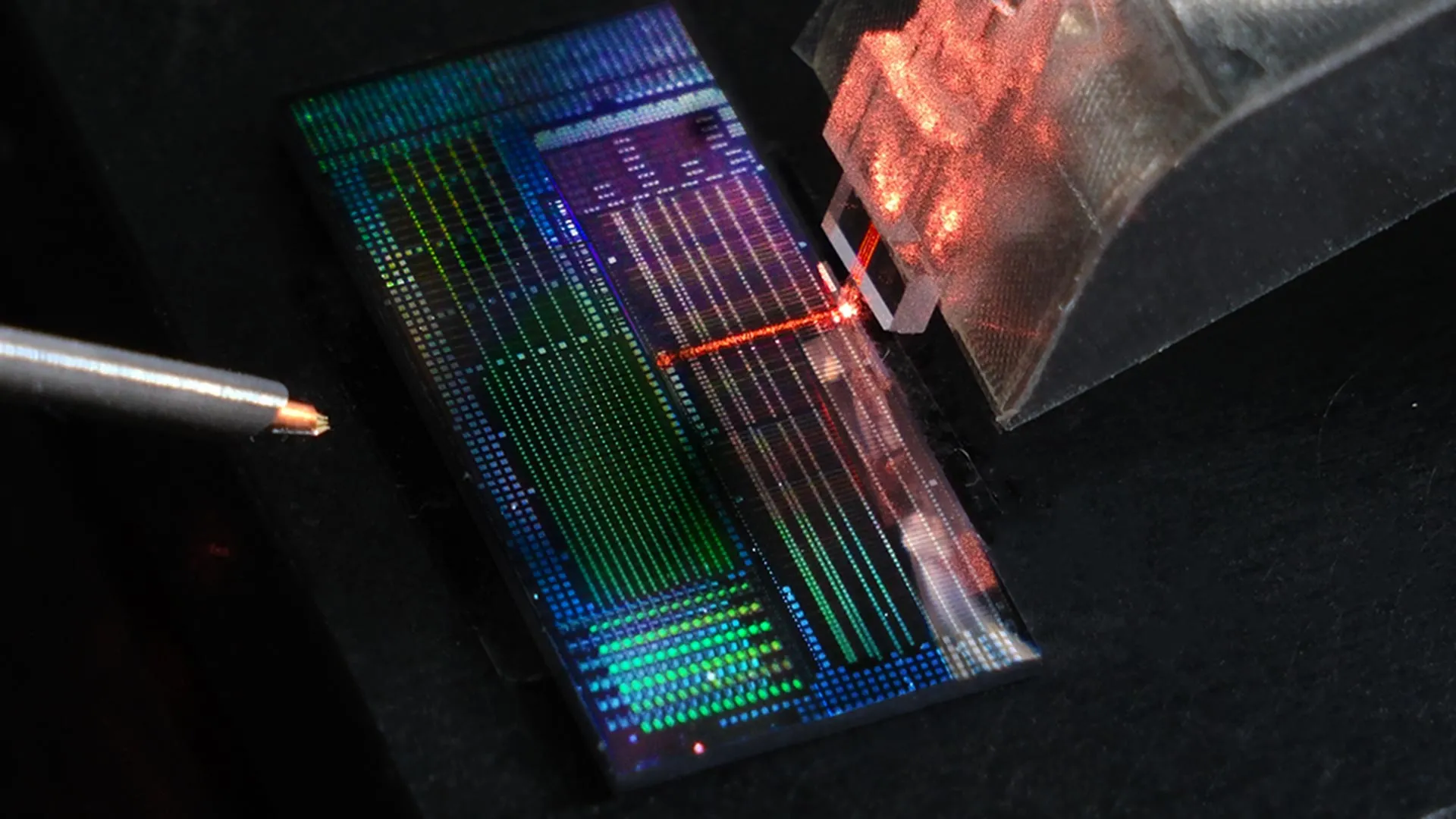

"This is why we now turn to emulators like ours, which can drastically cut time and resources," Bonici emphasizes. The fundamental principle behind an emulator is its ability to mimic the outputs of the more complex model. At its core lies a neural network, a type of artificial intelligence that learns to establish a precise association between input parameters and the model’s pre-computed predictions. The neural network is meticulously "trained" on a vast array of the model’s outputs. Once this training is complete, the emulator can generalize its knowledge, enabling it to predict the model’s response for combinations of parameters it has not encountered during training. It’s crucial to understand that the emulator does not "understand" the underlying physics in the same way a theoretical model does. Instead, it becomes exceptionally adept at recognizing and anticipating the theoretical model’s responses based on the patterns it has learned.

The true innovation of Effort.jl lies in its ability to further accelerate the training phase. It achieves this by ingeniously incorporating existing scientific knowledge about how predictions change when parameters are subtly altered. Instead of forcing the neural network to "re-learn" these fundamental relationships from scratch, Effort.jl leverages this pre-existing understanding from the outset. Furthermore, Effort.jl utilizes "gradients" – essentially, information about "how much and in which direction" predictions are expected to change if a parameter is tweaked by a minuscule amount. This inclusion of gradient information is another key factor that allows the emulator to learn effectively from significantly fewer examples. This reduction in learning examples directly translates to lower computational demands, enabling the emulator to operate efficiently on less powerful hardware, such as standard laptops.

The development of such a powerful tool necessitates extensive validation to ensure its reliability. If an emulator doesn’t possess a deep understanding of the underlying physics, how can scientists be certain that its computational shortcut is yielding accurate results – specifically, answers that are consistent with what the more complex model would produce? The newly published study directly addresses this critical question. It provides compelling evidence that Effort.jl’s accuracy, when tested on both simulated and real astronomical data, aligns remarkably well with the predictions of the theoretical model. "And in some cases," Bonici proudly concludes, "where with the model you have to trim part of the analysis to speed things up, with Effort.jl we were able to include those missing pieces as well." This capability to retain crucial details that might otherwise be sacrificed for speed underscores the power of Effort.jl. Consequently, Effort.jl emerges as an invaluable ally for the scientific community, poised to play a pivotal role in analyzing the forthcoming data releases from groundbreaking experiments like DESI and Euclid. These upcoming datasets promise to exponentially expand our knowledge of the Universe’s large-scale structure, pushing the boundaries of cosmological understanding further than ever before.

The seminal study, titled "Effort.jl: a fast and differentiable emulator for the Effective Field Theory of the Large Scale Structure of the Universe," authored by Marco Bonici, Guido D’Amico, Julien Bel, and Carmelita Carbone, is now publicly accessible in the esteemed Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (JCAP).