Nuclear fusion, the very process that powers our sun and stars, involves the merging of two light atomic nuclei to form a heavier one, releasing an enormous amount of energy in the process. For decades, scientists worldwide have tirelessly pursued ways to harness this immense power as a viable, sustainable energy source, free from the carbon emissions and long-lived radioactive waste associated with traditional fission reactors. The appeal is clear: fusion fuel (isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium, and tritium) is abundant, and the energy output is staggering. However, replicating stellar conditions on Earth presents an extraordinary challenge.

The fundamental hurdle lies in overcoming the natural electrostatic repulsion between atomic nuclei. All atomic nuclei carry a positive charge, meaning they naturally repel each other, much like two magnets with identical poles. To force them close enough to fuse, they must be heated to unfathomably high temperatures – around 150 million Kelvin, or approximately 27 million degrees Fahrenheit – transforming the fuel into a super-heated, ionized gas known as plasma. At these extreme temperatures, the nuclei possess enough kinetic energy to overcome their mutual repulsion and fuse.

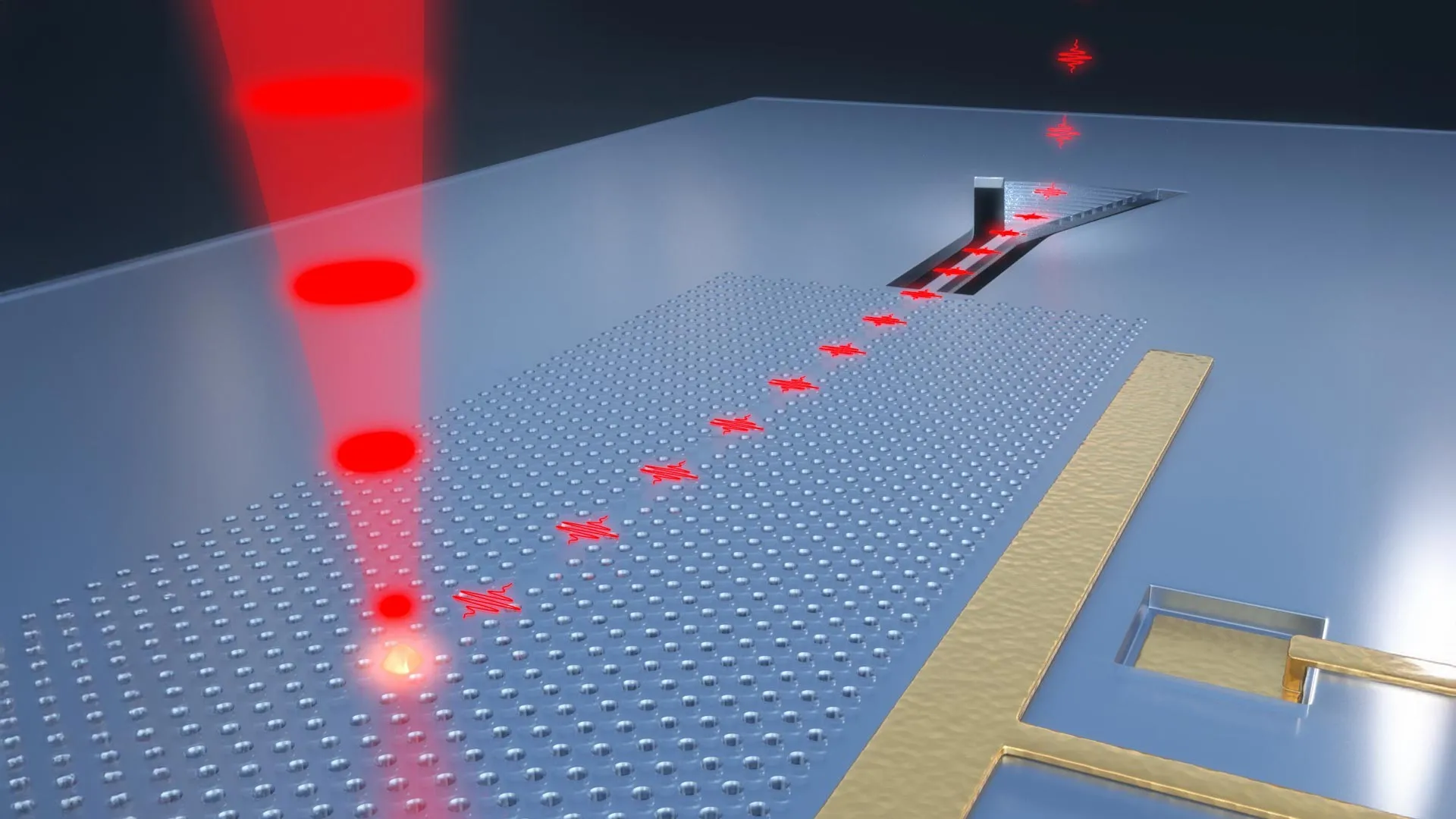

Yet, achieving these temperatures is only one part of the equation. For a fusion reaction to be sustainable and produce more energy than it consumes – a state known as "ignition" – the super-dense plasma must also remain hot, dense, and stable for extended periods. This is where magnetic confinement devices like tokamaks come into play. Tokamaks, with their distinctive doughnut-shaped vacuum chambers, use powerful magnetic fields to confine and control the scorching plasma, preventing it from touching the reactor walls, which would instantly cool it and halt the reaction.

For many years, fusion researchers have grappled with an empirical barrier known as the Greenwald limit. Proposed by Martin Greenwald of MIT in the 1980s, this limit suggested an upper bound on the achievable plasma density within a tokamak. The prevailing understanding was that if plasma density exceeded this threshold, it would inevitably lead to instabilities, causing the plasma to become turbulent, lose confinement, and ultimately collapse – a disruptive event that could damage the reactor and extinguish the fusion reaction. This limit has profoundly influenced tokamak design and operational strategies, acting as a seemingly immovable ceiling on performance and efficiency. Overcoming it was considered a major prerequisite for future high-performance fusion devices.

However, the EAST team’s latest research fundamentally challenges this long-held belief. Their innovative approach involved a meticulous manipulation of the reactor environment and plasma dynamics. Crucially, they introduced a high gas pressure environment within the tokamak prior to the formation of the plasma. This seemingly subtle change allowed the plasma to interact with the reactor wall in a significantly less destructive manner than previously observed. By carefully managing the initial conditions, the researchers could mitigate the onset of instabilities that typically plague high-density plasmas.

Furthermore, the scientists developed a method to manually pump extra energy into the plasma as it heated and increased in density. This carefully controlled energy injection ensured a more even and stable rise in plasma density, preventing localized hot spots or pressure gradients that could trigger instabilities. The combination of these techniques – the pre-plasma gas management and the controlled energy input – enabled the EAST device to maintain plasma stability even as its internal density soared to levels "far exceeding empirical limits," as the study eloquently states. This breakthrough isn’t merely about achieving a higher number; it’s about fundamentally altering the interaction dynamics between the plasma and its confinement system, demonstrating a new regime of stable, high-density operation.

The implications of shattering the Greenwald limit are profound and far-reaching for the global fusion research community. Scientifically, this achievement represents a paradigm shift, forcing a re-evaluation of fundamental plasma physics principles and the theoretical models that underpin tokamak operation. It suggests that the perceived constraints on plasma density were not absolute physical laws but rather limitations of previous operational methodologies and understanding. This opens up entirely new avenues for theoretical exploration and experimental validation.

From an engineering perspective, this breakthrough offers a "practical and scalable pathway," as Ping Zhu, a co-author of the study and plasma physicist at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, aptly noted. Future fusion reactors, including the colossal International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) currently under construction in France, and subsequent demonstration power plants (DEMO), could potentially be designed to operate at significantly higher plasma densities. Higher density directly translates to more fusion reactions per unit volume, which could lead to more compact, efficient, and ultimately more powerful fusion devices. It could allow for smaller reactors to achieve the same power output, or existing designs to produce much more power, dramatically improving the economic viability of fusion power. This directly addresses one of the critical components of the "triple product" – the combination of plasma temperature, density, and confinement time – which must reach a certain threshold for net energy gain. By pushing the density limit, EAST has made a substantial contribution to achieving this triple product.

China’s leadership in this area also underscores its growing prominence in green energy innovation and scientific research. The nation has invested heavily in advanced energy technologies, from solar and wind power to cutting-edge nuclear fusion, positioning itself at the forefront of the global transition to sustainable energy. The "artificial sun" moniker for EAST is not just a catchy phrase; it reflects a national ambition to harness the most powerful energy source known to humanity. This fusion breakthrough is another significant "notch on China’s lengthy green energy belt," demonstrating a concerted effort to tackle climate change and secure long-term energy independence through technological advancement.

While the breaking of the Greenwald limit marks a monumental stride, it is important to contextualize it within the broader landscape of fusion research. Many challenges still lie ahead on the path to practical fusion power. These include achieving sustained confinement times (keeping the plasma hot and dense for very long durations), developing robust and resilient materials capable of withstanding the extreme neutron flux generated by fusion reactions, and efficiently breeding tritium fuel within the reactor itself. Researchers globally, from the ITER project to private ventures like Commonwealth Fusion Systems and Helion, are working on various aspects of these challenges, utilizing different magnetic configurations and confinement strategies. Each breakthrough, whether in plasma density, temperature, or confinement time, contributes a vital piece to the complex puzzle of fusion.

In conclusion, the achievement at China’s EAST tokamak is more than just a scientific record; it is a testament to human ingenuity and perseverance in the pursuit of a sustainable energy future. By shattering a long-standing empirical limit on plasma density, the EAST team has not only pushed the boundaries of what was thought possible in magnetic confinement fusion but has also illuminated a clearer, more practical pathway towards harnessing the power of an artificial sun. This pivotal moment reinvigorates the global quest for fusion energy, offering renewed hope that a future powered by clean, virtually limitless energy may indeed be within humanity’s grasp.