The relentless pursuit of quantum computing’s full potential hinges on the ability to corral vast numbers of qubits, the fundamental building blocks that promise to revolutionize fields from physics and chemistry to medicine and materials science. Unlike the binary certainty of classical bits, qubits possess the remarkable capability to exist in multiple states simultaneously, a phenomenon known as superposition. This quantum quirk imbues quantum computers with the theoretical power to eclipse their classical counterparts in tackling specific, profoundly complex calculations. However, this very power comes with inherent fragility; qubits are notoriously susceptible to environmental noise and decoherence. To mitigate these vulnerabilities and pave the way for reliable quantum computation, researchers are embracing a strategy of redundancy, building quantum machines equipped with an abundance of extra, auxiliary qubits dedicated to error detection and correction. This proactive approach underscores a crucial reality: the realization of robust, fault-tolerant quantum computers will necessitate the orchestration of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of these delicate quantum units.

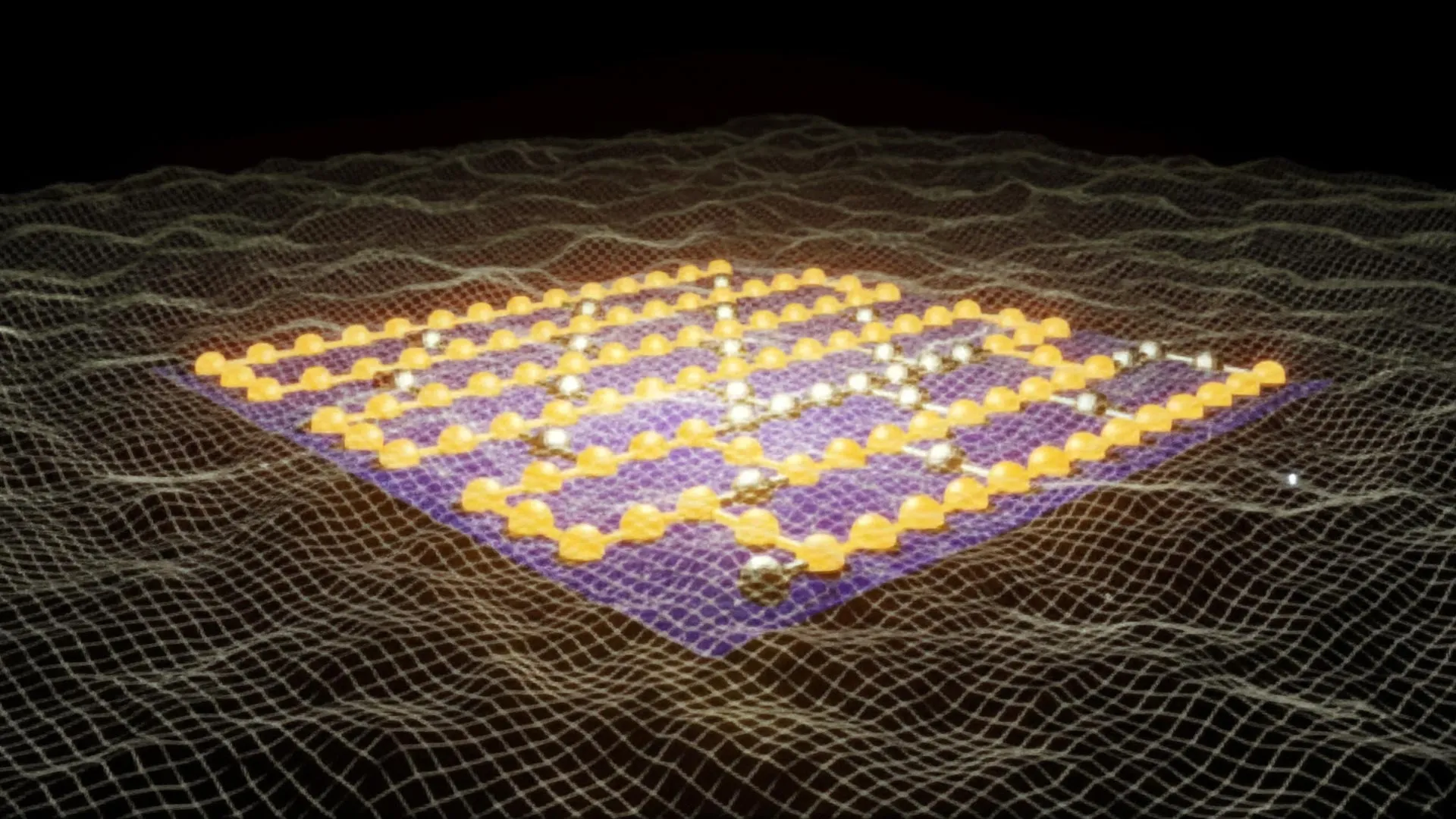

In a significant stride towards this ambitious future, a team of physicists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) has achieved a groundbreaking milestone: the creation of the largest neutral-atom qubit array ever assembled, boasting an astonishing 6,100 qubits meticulously arranged and trapped within a grid by precisely controlled laser beams. This feat dramatically surpasses previous neutral-atom arrays, which typically contained only hundreds of qubits, marking a dramatic leap in scale and complexity. This monumental achievement arrives at a pivotal moment in the global quantum computing race, a dynamic and rapidly escalating competition characterized by diverse technological approaches. Alongside the neutral-atom platform, other leading contenders include superconducting circuits and trapped ions, each with its unique strengths and challenges.

"This is an incredibly exciting moment for neutral-atom quantum computing," declared Manuel Endres, a professor of physics at Caltech and the principal investigator of the groundbreaking research published on September 24 in the prestigious journal Nature. "We can now clearly envision a viable pathway towards building large-scale, error-corrected quantum computers. The fundamental building blocks are now firmly in place." The pioneering study was spearheaded by three Caltech graduate students: Hannah Manetsch, Gyohei Nomura, and Elie Bataille, whose dedication and ingenuity were instrumental in this scientific breakthrough.

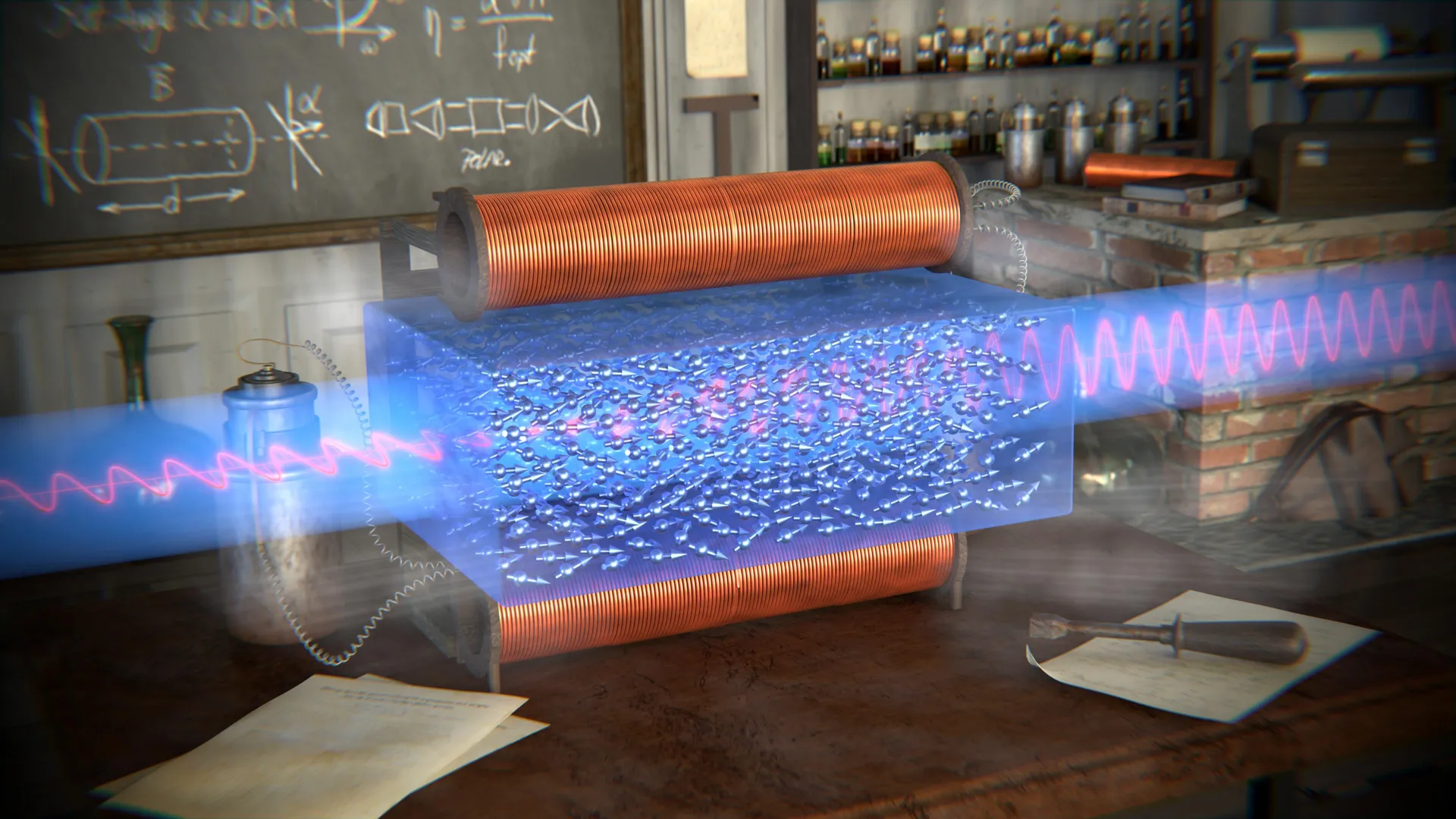

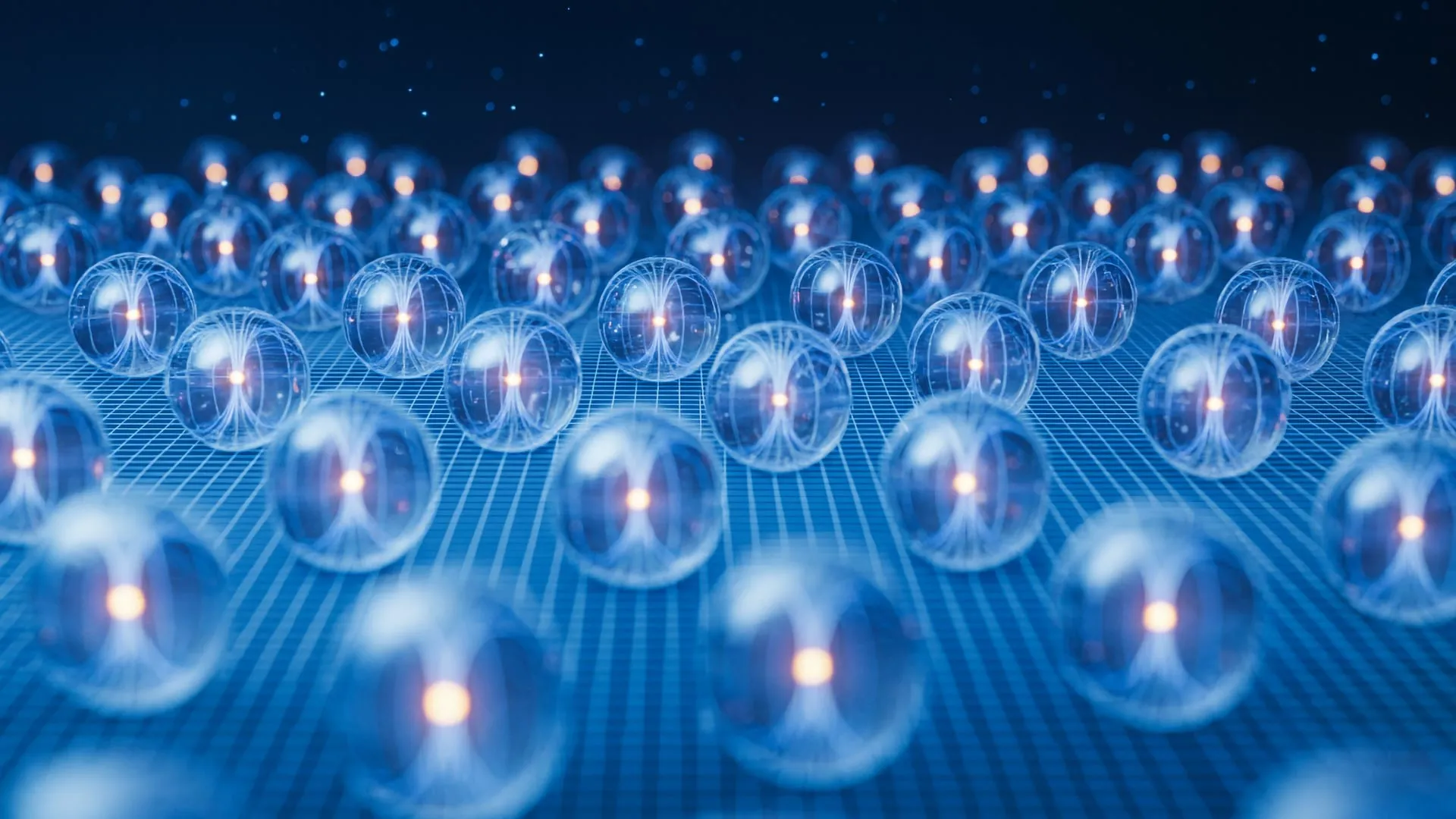

The Caltech team’s innovative approach hinges on the sophisticated use of optical tweezers – highly focused laser beams capable of exerting precise control over individual atoms. By splitting a single laser beam into an array of 12,000 individual tweezers, the researchers were able to capture and hold 6,100 individual cesium atoms within a meticulously controlled vacuum chamber, forming a highly ordered grid. "On the screen, we can actually see each qubit as a pinpoint of light," shared Manetsch, vividly describing the visual representation of this complex quantum hardware. "It’s a striking image of quantum hardware at a truly large scale, a testament to our ability to manipulate matter at its most fundamental level."

A critical aspect of this research was demonstrating that this substantial increase in qubit numbers did not come at the expense of qubit quality – a common concern when scaling up quantum systems. Remarkably, even with over 6,000 qubits meticulously arranged in a single array, the team managed to maintain their fragile superposition states for an impressive duration of approximately 13 seconds. This represents a nearly tenfold improvement over previous similar arrays, a significant advancement in coherence times. Furthermore, the researchers achieved an extraordinary manipulation accuracy of 99.98 percent when addressing and controlling individual qubits. "Large scale, with more atoms, is often thought to come at the expense of accuracy, but our results show that we can achieve both," emphasized Nomura, highlighting the dual triumph of quantity and quality. "Qubits simply aren’t useful without a high degree of quality. Now, we possess both the quantity and the quality necessary for advanced quantum operations."

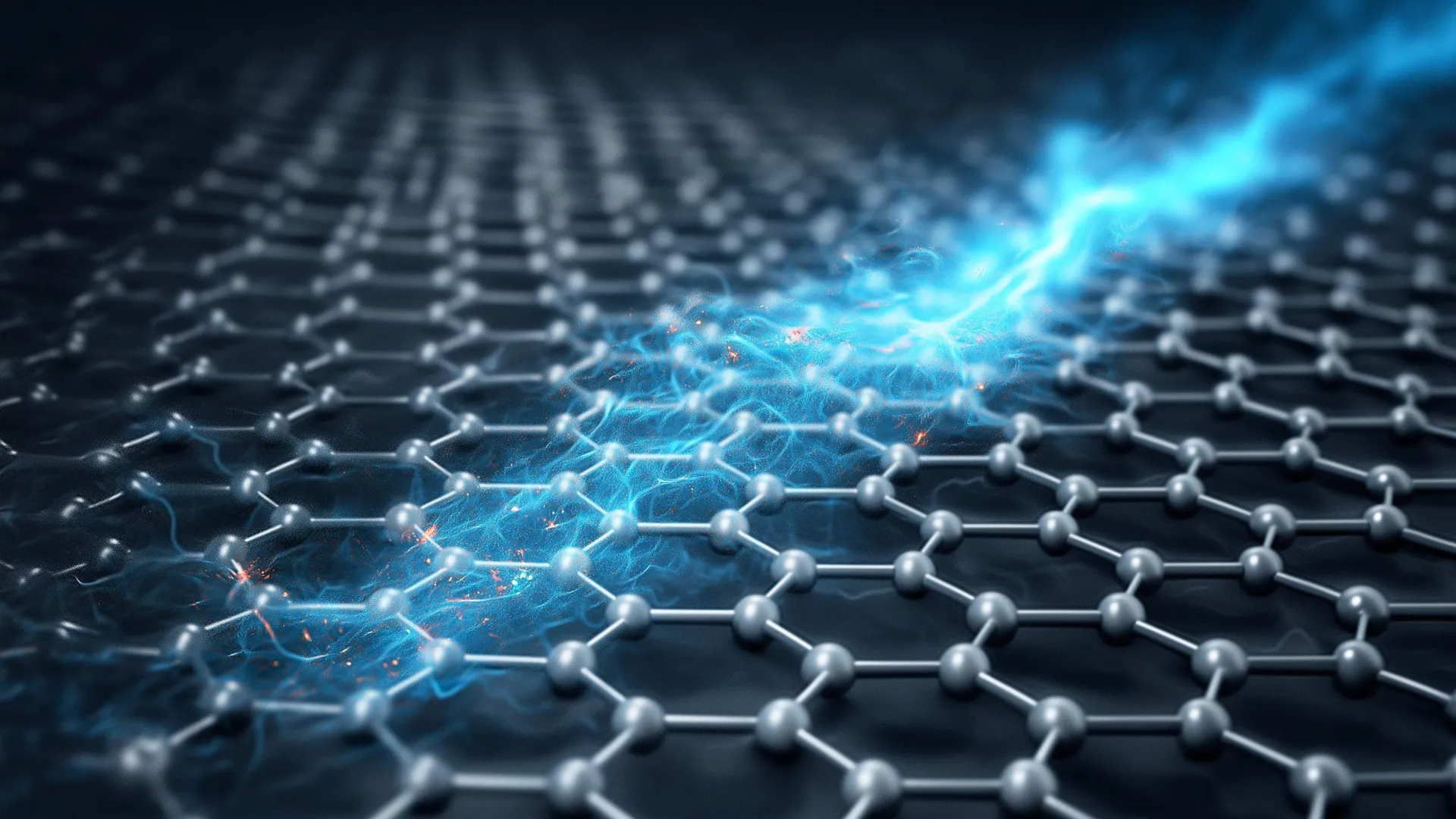

Adding another layer of sophistication to their achievement, the team successfully demonstrated the ability to move individual atoms across the array by hundreds of micrometers while rigorously maintaining their delicate superposition states. This capacity to shuttle qubits is a defining advantage of neutral-atom quantum computers, enabling more efficient and flexible error correction strategies compared to more rigid, hard-wired platforms like superconducting qubits, where physical rewiring can be cumbersome or impossible.

Manetsch eloquently illustrated the inherent difficulty of this task by drawing a relatable analogy: "Trying to hold an atom while moving it is akin to trying to balance a glass of water while running. The challenge of not letting the glass tip over is significant, but trying to simultaneously keep the atom in a state of superposition is like being so careful that you don’t run so fast that the water splashes over the rim." This vivid comparison underscores the exquisite precision and control required to manipulate these quantum systems.

The next significant hurdle for the broader field of quantum computing is the practical implementation of quantum error correction at the scale of thousands of physical qubits. The Caltech team’s work provides compelling evidence that neutral atoms represent a highly promising candidate platform for achieving this ambitious goal. "Quantum computers will absolutely have to encode information in a way that is inherently tolerant to errors, so that we can actually perform meaningful and reliable calculations," explained Bataille, underscoring the critical importance of error mitigation. "Unlike in classical computers, qubits cannot simply be copied due to the fundamental principle known as the no-cloning theorem. Therefore, error correction must rely on far more subtle and sophisticated strategies to protect quantum information."

Looking towards the horizon, the researchers are actively planning the next phase of their work, which involves linking the qubits within their impressive array into a state of entanglement. Entanglement, a profound quantum phenomenon where particles become inextricably correlated and behave as a single, unified entity, is a prerequisite for quantum computers to transcend mere information storage and embark on performing full-fledged quantum computations. It is precisely this emergent property of entanglement that unlocks the ultimate power of quantum computers: their capacity to simulate nature itself with unprecedented fidelity. In the natural world, entanglement plays a pivotal role in shaping the behavior of matter at every conceivable scale, from subatomic particles to vast cosmic structures. The overarching goal is clear: to harness the power of entanglement to unlock revolutionary scientific discoveries, ranging from revealing exotic new phases of matter to guiding the design of novel materials with tailored properties, and to accurately modeling the complex quantum fields that govern the very fabric of space-time.

"It is profoundly exciting that we are actively creating machines that will help us understand the universe in ways that only the principles of quantum mechanics can illuminate," concluded Manetsch, expressing the profound scientific aspirations driving this research.

The groundbreaking study, titled "A tweezer array with 6100 highly coherent atomic qubits," received generous funding from a consortium of esteemed organizations, including the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Weston Havens Foundation, the National Science Foundation (through its Graduate Research Fellowship Program and the Institute for Quantum Information and Matter at Caltech), the Army Research Office, the U.S. Department of Energy (including its Quantum Systems Accelerator initiative), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Air Force Office for Scientific Research, the Heising-Simons Foundation, and the AWS Quantum Postdoctoral Fellowship. The research team also included Caltech’s Kon H. Leung, an AWS Quantum senior postdoctoral scholar research associate in physics, and former Caltech postdoctoral scholar Xudong Lv, now affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences.