Researchers at Rice University have achieved a groundbreaking feat, demonstrating that specific atom-thin semiconductors, known as transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), can undergo physical atomic lattice shifts when illuminated by light. This newly observed phenomenon, dubbed "optostriction" in this context, offers an unprecedented level of control over the behavior and properties of these ultrathin materials, opening exciting avenues for future technological advancements that leverage light for information processing and sensing. The implications are far-reaching, potentially leading to faster, cooler computing, highly sensitive detectors, and advanced optoelectronic systems.

The remarkable light-induced atomic motion was observed in a specialized class of TMDs known as Janus materials. These materials derive their name from the Roman god of transitions, Janus, who famously had two faces looking in opposite directions, a fitting analogy for the asymmetric nature of these atomic structures. Their heightened sensitivity to light and external forces stems from a unique compositional imbalance. Unlike conventional TMDs, which consist of stacked layers of a transition metal (like molybdenum) sandwiched between two identical chalcogen layers (such as sulfur or selenium), Janus materials feature different chemical elements in their top and bottom atomic layers. This structural asymmetry imbues them with a built-in electrical polarity, making them exceptionally responsive to external stimuli, particularly light.

"In the realm of nonlinear optics, we’ve long known that light can be manipulated to generate new colors, create faster pulses, or act as optical switches that control signal flow," explained Kunyan Zhang, a Rice doctoral alumna and the study’s first author. "The beauty of two-dimensional materials, being only a few atoms thick, is that they allow us to miniaturize these optical tools to an incredible degree. Our work takes this a step further by showing that light itself can be used to actively sculpt the atomic arrangement within these materials."

The fundamental building blocks of TMDs are layered structures where a transition metal atom is bonded to two chalcogen atoms. This arrangement, repeated in layers, results in materials with a compelling combination of electrical conductivity, potent light absorption capabilities, and remarkable mechanical flexibility. These properties have positioned TMDs as prime candidates for the next generation of electronic and optical devices. However, it is the specific structural asymmetry of Janus materials that sets them apart. This inherent imbalance creates an internal electric dipole moment, which in turn amplifies their susceptibility to optical and mechanical influences.

"Our research delves into the intricate relationship between the specific atomic structure of Janus materials and their optical responses," Zhang elaborated. "Crucially, we’ve uncovered how light can exert a tangible physical force within these materials, leading to observable atomic displacement."

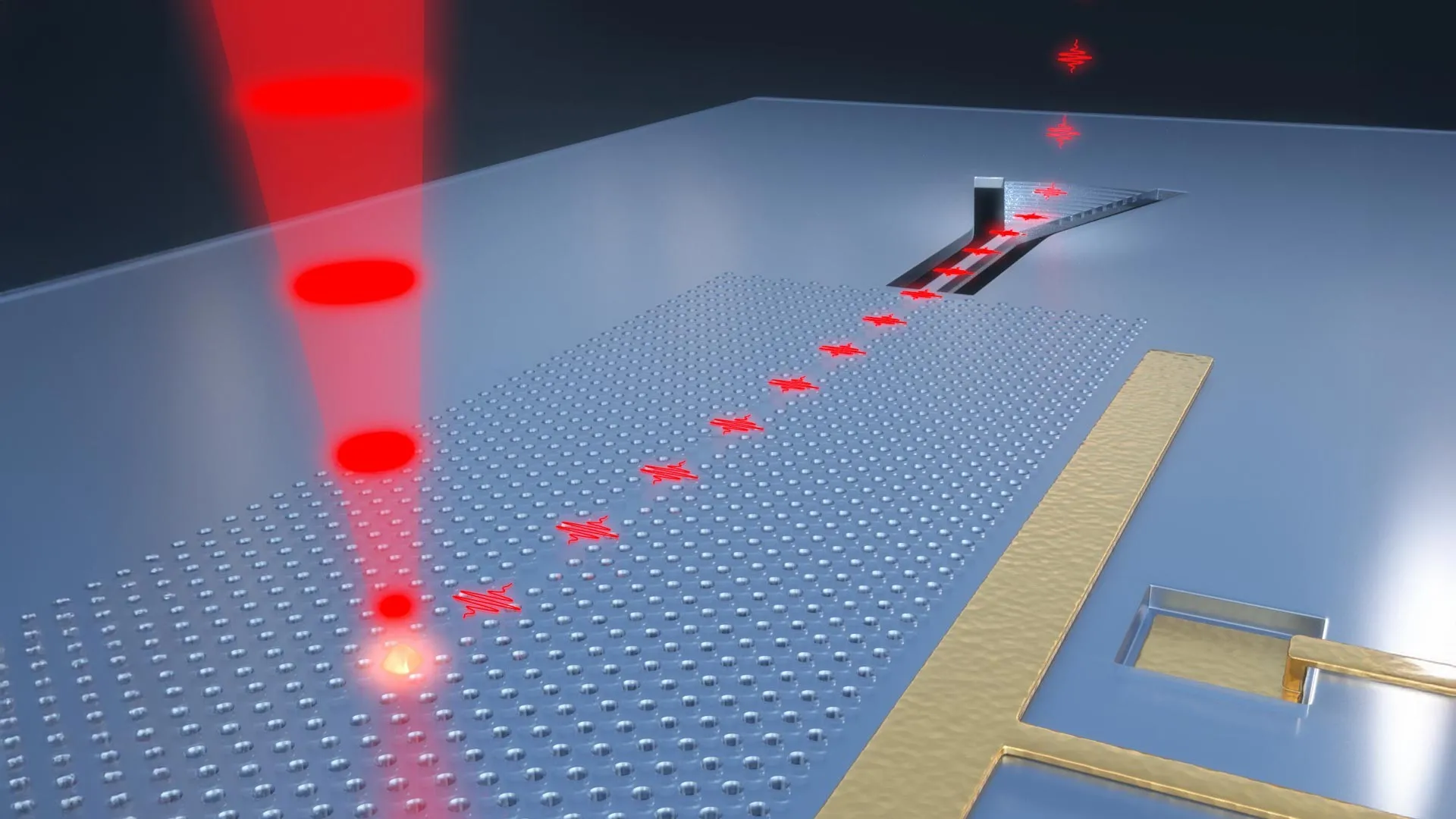

To meticulously investigate this light-induced atomic motion, the Rice team employed a sophisticated experimental setup. They directed laser beams of varying wavelengths onto a carefully engineered two-layer Janus TMD material. This specific sample comprised molybdenum sulfur selenide stacked atop molybdenum disulfide, creating a precisely controlled asymmetric interface. The researchers then probed the material’s response by analyzing how it modified the incident light through a process known as second harmonic generation (SHG). In SHG, a material absorbs photons of a certain frequency and re-emits photons at precisely double that frequency.

The key to their discovery lay in observing deviations from the expected SHG pattern. When the frequency of the incoming laser light resonated with the material’s natural electronic transitions, the standard SHG signal, which typically exhibits a distinct symmetrical "flower" pattern mirroring the crystal’s symmetry, became distorted. This distortion was not random; it revealed a breakdown in the material’s inherent symmetry, indicating that the atoms were physically shifting in response to the light.

"We observed that when light interacts with Janus molybdenum sulfur selenide and molybdenum disulfide, it generates minuscule, yet directional, forces within the material," Zhang detailed. "These forces manifest as alterations in the SHG pattern. Ordinarily, the SHG signal presents a six-pointed ‘flower’ shape, a direct reflection of the crystal’s symmetry. However, when light imparts a physical push on the atoms, this symmetry is disrupted – the petals of the flower shrink unevenly, providing a visual fingerprint of the atomic movement."

The researchers identified the underlying physical mechanism responsible for this SHG distortion as optostriction. Optostriction is a phenomenon where the oscillating electromagnetic field of light exerts a mechanical force on the atoms within a material. In the case of Janus materials, the strong coupling between their atomically distinct layers acts as an amplifier for this optostrictive effect. This enhanced coupling means that even extremely subtle forces, generated by the light’s electric field, can induce measurable strain or deformation in the material’s atomic lattice.

"Janus materials are ideally suited for observing optostriction because their non-uniform composition leads to a significantly enhanced interaction between their stacked layers," Zhang explained. "This heightened coupling makes them extraordinarily sensitive to the minute forces exerted by light. These forces are so small that directly measuring them would be exceedingly challenging, but their impact is readily detectable through the changes they induce in the SHG signal pattern."

The high sensitivity of Janus materials to light-induced atomic motion has profound implications for the development of future optical technologies. Devices that can actively guide or control light using this optostrictive mechanism hold the promise of revolutionizing photonics. Photonic chips, which utilize light to transmit and process information instead of electrical currents, are inherently more energy-efficient and generate significantly less heat than their electronic counterparts. By enabling precise control over light-matter interactions at the atomic scale, Janus materials could be instrumental in designing next-generation photonic circuits that are both faster and more power-efficient.

Beyond computing, these properties could be harnessed to create ultrasensitive sensors capable of detecting minute vibrations, pressure changes, or even chemical signatures. Imagine a sensor that can detect the faintest seismic activity or the subtle changes in atmospheric pressure. Furthermore, the tunable nature of light-matter interactions in Janus materials could lead to the development of adjustable light sources for advanced display technologies and sophisticated imaging systems, offering unprecedented control over light emission and manipulation.

"The ability to actively control light at the nanoscale using these materials opens up a wealth of possibilities for designing next-generation photonic chips, ultrasensitive detectors, and even quantum light sources," commented Shengxi Huang, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, materials science and nanoengineering at Rice, and a corresponding author of the study. Huang, who is also affiliated with the Smalley-Curl Institute, the Rice Advanced Materials Institute, and the Ken Kennedy Institute, emphasized the shift towards light-based information processing. "These are technologies that leverage light to carry and process information, fundamentally moving away from the limitations of traditional electricity."

The study’s findings underscore a critical principle in materials science: even seemingly minor structural imbalances can unlock significant technological opportunities. By demonstrating how the internal asymmetry of Janus TMDs provides a novel mechanism for influencing the flow and behavior of light, the research highlights the immense potential embedded within subtle atomic-level engineering. This breakthrough serves as a compelling example of how understanding and manipulating the fundamental properties of matter at the nanoscale can pave the way for transformative technological advancements.

The research was generously supported by funding from the National Science Foundation (grants 2246564 and 1943895), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (grant FA9550-22-1-0408 and FA2386-24-1-4049), the Welch Foundation (grant C-2144), the U.S. Department of Energy (grants DE–SC0020042 and DE-AC02-05CH11231), and the Taiwan Ministry of Education. The content presented in this article is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views or positions of the funding organizations and institutions involved.