In a groundbreaking development that could redefine the landscape of artificial intelligence and computing, scientists at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering and the School of Advanced Computing have successfully engineered artificial neurons that meticulously replicate the complex electrochemical behavior of their biological counterparts. This seminal discovery, detailed in the prestigious journal Nature Electronics, represents a monumental stride in the burgeoning field of neuromorphic computing. Neuromorphic computing is dedicated to designing hardware architectures that are fundamentally inspired by the intricate structure and function of the human brain. The implications of this breakthrough are far-reaching, with the potential to drastically reduce the physical footprint of computational chips by orders of magnitude, achieve dramatic reductions in energy consumption, and propel artificial intelligence closer to the elusive goal of artificial general intelligence (AGI) – a form of AI capable of understanding, learning, and applying knowledge across a wide range of tasks at a human level.

The fundamental difference between these novel artificial neurons and existing digital processors, or even earlier generations of neuromorphic chips, lies in their operational paradigm. While conventional systems simulate brain activity through abstract mathematical models, these new artificial neurons physically embody the actual mechanisms by which real neurons function. In the biological brain, neural activity is initiated and propagated through a sophisticated interplay of chemical and electrical signals. These advanced artificial neurons mirror this biological reality by employing actual chemical interactions to trigger and orchestrate computational processes. This departure from purely symbolic representation signifies a tangible recreation of biological function, moving beyond mere simulation to true emulation.

A New Class of Brain-Like Hardware Emerges

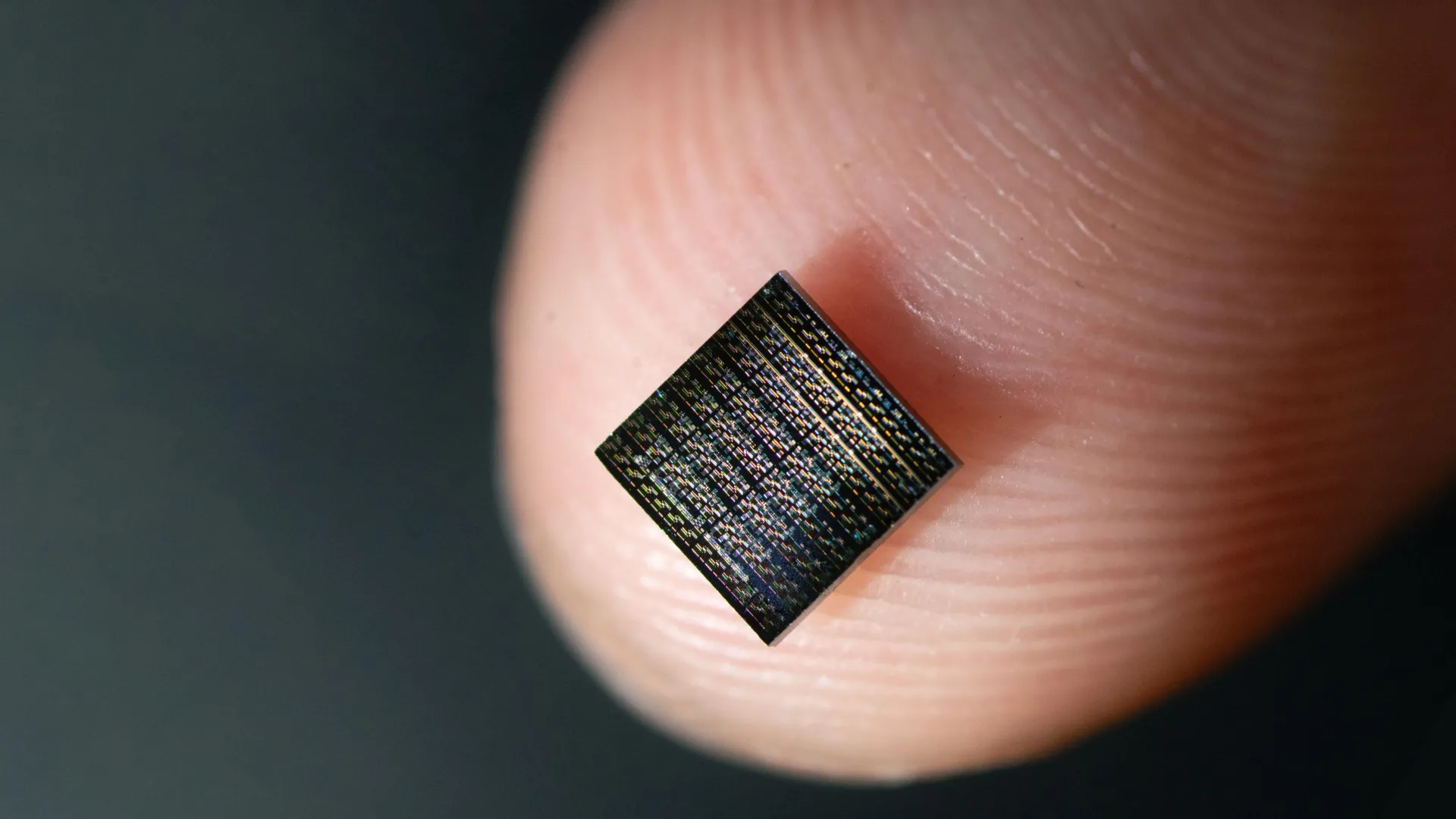

The pioneering research, spearheaded by Professor Joshua Yang of USC’s Department of Computer and Electrical Engineering, builds upon his decade-old foundational work on artificial synapses. The team’s innovative approach centers on a specialized device known as a "diffusive memristor." Their published findings elucidate how these unique components could pave the way for an entirely new generation of integrated circuits that not only complement but also significantly enhance traditional silicon-based electronics. While conventional silicon systems rely on the flow of electrons to perform computations, Yang’s diffusive memristors harness the movement of atoms, a process that more closely aligns with the natural transmission of information within biological neurons. The ultimate outcome of this paradigm shift is the creation of smaller, more energy-efficient chips that process information in a manner strikingly similar to the human brain, potentially unlocking the door to AGI.

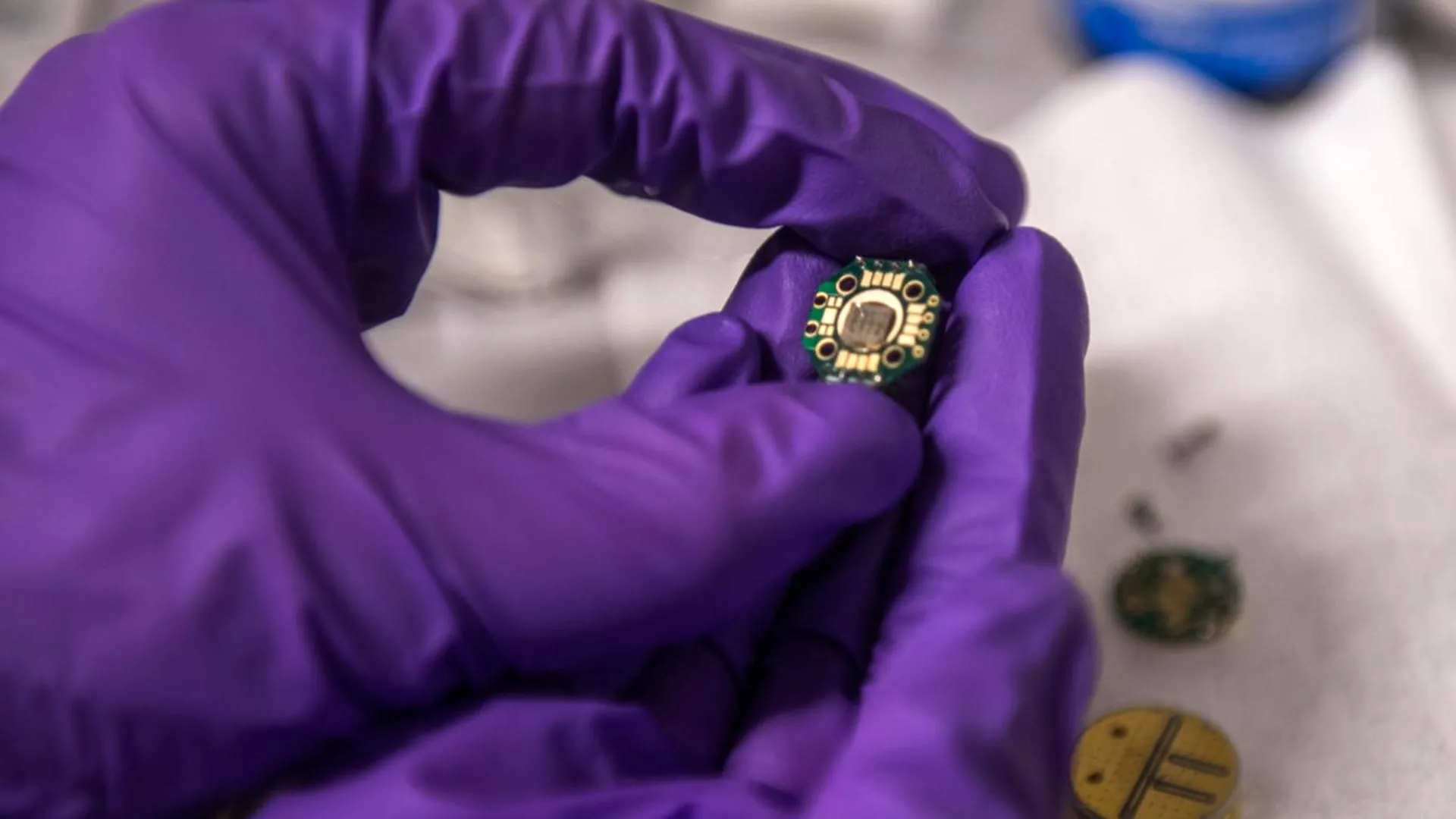

The intricate dance of communication between nerve cells in the brain is orchestrated by a dynamic interplay of both electrical and chemical signals. When an electrical impulse traverses a neuron and reaches its terminal, a junction known as a synapse, it undergoes a transformation into a chemical signal. This chemical messenger then diffuses across the synaptic gap to transmit information to an adjacent neuron. Upon reception, this chemical signal is reconverted into an electrical impulse, which then propagates through the receiving neuron, continuing the neural communication cascade. Yang and his collaborators have achieved an astonishing degree of accuracy in replicating this complex biological process within their artificial devices. A particularly significant advantage of their design is its remarkable spatial efficiency: each artificial neuron occupies a physical footprint equivalent to that of a single transistor, a stark contrast to previous designs that required tens or even hundreds of transistors to achieve comparable functionality.

Within biological neurons, the generation of electrical impulses that drive neural activity is facilitated by charged particles known as ions. The human nervous system relies heavily on the precise movement of specific ions, including potassium, sodium, and calcium, to enable its vast array of functions.

Harnessing Silver Ions to Recreate Brain Dynamics with Unprecedented Fidelity

In their latest groundbreaking study, Professor Yang, who also holds the distinguished position of Director of the USC Center of Excellence on Neuromorphic Computing, ingeniously employed silver ions embedded within oxide materials to generate electrical pulses that faithfully mimic the fundamental processes of natural brain functions. These emulated functions encompass critical cognitive and operational capabilities such as learning, motor control, and strategic planning.

"Even though the specific ions used in our artificial synapses and neurons are not identical to those found in biological systems, the underlying physics governing ion motion and the resultant dynamics are remarkably similar," explains Professor Yang. He elaborates on the team’s choice of material: "Silver possesses excellent diffusion properties, allowing us to achieve the precise dynamics necessary to emulate the biosystem. This enables us to replicate neuronal function with a remarkably simple structural design." The novel device responsible for enabling these brain-like chips is aptly named the "diffusive memristor," a designation that underscores the crucial role of ion motion and the dynamic diffusion facilitated by the use of silver.

Professor Yang further articulates the strategic rationale behind their decision to leverage ion dynamics for the construction of artificial intelligent systems: "This is precisely how the human brain operates, and for good reason. The human brain is the undisputed ‘winner in evolution’ – the most efficient intelligent engine known to us." This emphasis on efficiency is a core tenet of their research philosophy.

The Paramount Importance of Efficiency in Artificial Intelligence Hardware

Professor Yang underscores a critical insight into the limitations of modern computing: the primary challenge is not a deficit in computational power, but rather a pervasive lack of efficiency. "It’s not that our chips or computers are insufficient in terms of raw power for their intended tasks," he clarifies. "Rather, they are fundamentally inefficient, consuming an excessive amount of energy." This issue is particularly acute given the prodigious energy demands of today’s large-scale artificial intelligence systems, which are required to process immense volumes of data.

Yang elaborates on the fundamental divergence between biological and artificial systems: "Unlike the brain, our existing computing systems were never designed to process massive datasets or to independently learn from a limited number of examples. A key strategy for enhancing both energy efficiency and learning capabilities is to construct artificial systems that operate according to the principles observed in the brain."

While electrons, the workhorses of modern computing, offer unparalleled speed for rapid operations, Professor Yang posits that "ions represent a superior medium for embodying the principles of the brain." He explains that the lightweight and volatile nature of electrons facilitates software-based learning, a paradigm fundamentally distinct from the hardware-based learning characteristic of the brain. In contrast, he notes, "The brain learns by facilitating the movement of ions across membranes, thereby achieving energy-efficient and adaptive learning directly within its hardware – or, more accurately, what some might term ‘wetware’."

As a compelling illustration, Yang points to the remarkable learning ability of a young child who can recognize handwritten digits after encountering only a few examples of each. In stark contrast, conventional computers typically require thousands of examples to achieve the same level of proficiency. Astonishingly, the human brain accomplishes this feat of remarkable learning while consuming a mere 20 watts of power, a minuscule fraction of the megawatts demanded by today’s supercomputers.

Profound Potential Impact and the Road Ahead

Professor Yang and his dedicated team view this pioneering technology as a significant leap forward in the pursuit of replicating natural intelligence. However, he readily acknowledges a practical hurdle: the silver utilized in their current experimental setup is not yet fully compatible with established semiconductor manufacturing processes. Consequently, their future research will focus on exploring alternative ionic materials that can achieve comparable functional outcomes.

The diffusive memristors developed by the team offer exceptional efficiency in both energy consumption and physical size. A typical smartphone, for instance, contains approximately ten chips, each comprising billions of transistors that toggle on and off to execute calculations. "With this innovation," Yang states, "we can utilize the footprint of just one transistor for each neuron. We are meticulously designing the foundational building blocks that will ultimately enable us to reduce chip size by orders of magnitude and dramatically decrease energy consumption. This will pave the way for sustainable AI development in the future, achieving comparable levels of intelligence without the unsustainable energy expenditure."

With the successful demonstration of capable and remarkably compact building blocks – artificial synapses and neurons – the team is now poised to embark on the next critical phase: integrating vast numbers of these components and rigorously assessing their ability to replicate the brain’s efficiency and capabilities. "What is even more exciting," Professor Yang concludes, "is the prospect that such brain-faithful systems could offer invaluable new insights into the very workings of the human brain itself."