The history of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans dates back to the 1980s, with revisions typically occurring every five years. This process traditionally involves a dedicated team of nutrition scientists who meticulously review extensive research to inform a scientific report, followed by the official publication of the guidelines. The most recent iteration, intended for the 2020-2025 period, saw its scientific report released in 2024, but the final guidelines were delayed due to government shutdowns. Their eventual release in early 2026 surprised many, as some anticipated updates reflecting evolving nutrition science, such as the World Health Organization’s stance on the lack of a safe level of alcohol consumption, and emerging research on the health risks associated with ultra-processed foods. Environmental sustainability was also a factor many expected to be integrated into the new recommendations.

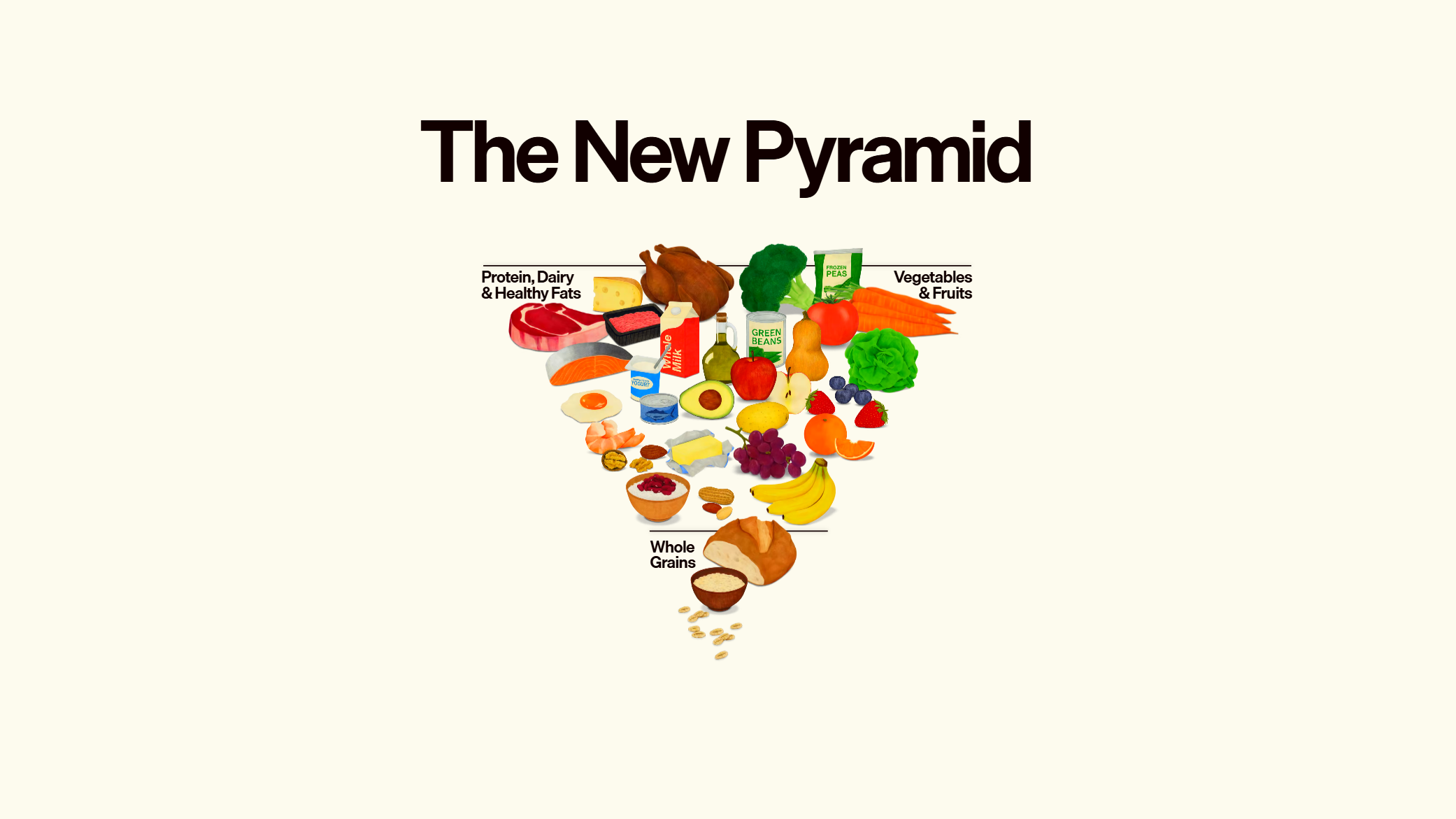

The newly unveiled guidelines present a "new pyramid" structure, an inverted triangle that places "protein, dairy, and healthy fats" alongside "vegetables and fruits" at the apex, with whole grains at the base. Nutritionists like Gabby Headrick, associate director of food and nutrition policy at George Washington University’s Institute for Food Safety & Nutrition Security, have criticized this visual representation. She notes that the scientific community has largely moved beyond food pyramids, finding them confusing and less effective than the more intuitive "MyPlate" model, which has been adopted by consumer-friendly nutrition education programs for over a decade, mirroring similar approaches in countries like the UK.

The content of this new pyramid is a primary source of contention. The prominent display of steak as the top left image, a stick of butter positioned centrally, and the inclusion of beef tallow as a "healthy fat" are seen as particularly problematic. While red meat and full-fat dairy can be part of a balanced diet, established scientific consensus has long recommended limiting their consumption due to high saturated fat content, a known contributor to cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in the U.S. The World Health Organization’s classification of red meat as "probably carcinogenic to humans" in 2015 further amplifies these concerns. Headrick points out the significant difference in saturated fat content between olive oil and fats like beef tallow and butter, highlighting that these latter options do not offer the same established health benefits. "I think these are pretty harmful dietary recommendations to be making when we have established that those specific foods likely do not have health-promoting benefits," she stated. Furthermore, the environmental impact of red meat and dairy production is a significant concern that the guidelines appear to overlook.

Another area of concern is the revised recommendation for protein intake, which has been increased to levels between 1.2 and 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight daily – a 50% to 100% increase from previous guidelines. José Ordovás, a senior nutrition scientist at Tufts University, cautions that such elevated protein consumption could inadvertently lead to excessive calorie and saturated fat intake. He advises erring on the lower side of these new recommendations.

The divergence of these new guidelines from the 2024 scientific report, and the lack of updated evidence supporting such significant shifts, has led many nutrition scientists to question the process. Sources close to the development of previous guidelines expressed frustration, with one describing the process for the new recommendations as "opaque." Ordovás echoed this sentiment, stating, "I’m not surprised that when they see that [their] work was ignored and replaced with something [put together] quickly, that they feel a little bit disappointed." This sentiment suggests a disconnect between the rigorous scientific review process and the final published guidelines, raising questions about the integrity and scientific basis of the government’s latest dietary advice.